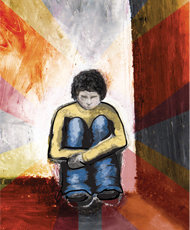

EB’s story, common in many ways and tragic in most, demonstrates why we — as advocates against harsh school discipline policies — fight against harsh school discipline policies that funnel children from school to jail. When EB was in the 4th grade, in Jackson, Miss., he was in the talented and gifted program. Around that time, a caring teacher noticed that he was being physically abused and reported it to the county. After this report, EB’s immediate family was broken up, he was separated from siblings, and he went to live with relatives. In a state that has few mental health resources and a foster care system in disarray, EB got little guidance, counseling or comfort. Rather, he returned to school and began to act out. As a result and without regard to his life circumstances, he was placed in Jackson’s alternative school programs where he moved through a revolving door of youth jails, mental health institutions, and alternative schools. Along the way, his fate was sealed. From 2005-2009, EB did not step foot inside a regular education classroom. Advocates fought for EB to return to regular school and the school board permitted EB to return to his regular high school for the 2009-2010 school year. After he was accused of breaking in to a middle school, we, as his advocates, defended EB and asked the Jackson Public School District not to expel him. Expulsion is generally not a solution to any child’s problem. If expelled, EB would have just had more time on the street, when what he wanted was an education. More importantly, we asked the school district to look at what they had done with and for EB in the five years prior to the expulsion. While our fight was worthwhile, it came too late.

This week EB pled guilty to a 2010 shooting in Jackson. EB bears responsibility for this, but we, as a society, can take some responsibility for it as well. Had he been permitted to stay in school as a 5th grader, the awful crime that he was sentenced for might not have occurred. Perhaps the school district could have identified the emotional and physical pain he was suffering from and with resources, addressed them at school rather than the already over-burdened youth court system in Mississippi. Perhaps he should have been identified as a student with special emotional needs instead of being placed in alternative school where he knew, as a bright young man, he was not being taught anything but compliance?

We will never know.

We do know that EB was born inside a prison; he may have never stood a chance in this world. He was raised in homes where he was abused, physically, sexually, emotionally and spiritually. And knowing EB’s history of jail, alternative school, and mental health issues, anyone who knows him is not surprised by this outcome. However, there a number of lingering questions that arise from a story like this. Do we not have an obligation to ensure that all children in America have an education, safety, and mental health treatment before something like this occurs? As a society, do we not have a duty to do our best to prevent the creation of other EBs by providing adequate mental health treatment for abused children and making schools a place of sanctuary rather than a gateway to jail or the street? In preventing other EBs, don’t we prevent ourselves and others from becoming victims of their crimes?

EB entered jail when he was arrested in June 2010 and, after being denied bail, he has been in jail awaiting trial ever since. When he was arraigned in a Hinds County, Miss., courtroom shortly after his arrest in June 2010, 35 EBs sat in the front of the courtroom with him. The first group: the misdemeanors; the second group: the felonies. Everyone was dressed in orange jumpsuits with shackles connecting ankles to waist to wrists. EB was the only one in yellow — for child. The others, like him: all African-American, all in jumpsuits, all in a place we will never understand. When EB went to jail in 2010, he joined the 100’s of other EBs just like him behind walls and metal bars. EB failed society, but we, as a society, must come to grips with how we failed EB.

UPDATE: The name of the above-mentioned teen’s name has been replaced with "EB" to protect his identity.

Learn more about the school-to-prison pipeline: Sign up for breaking news alerts, follow us on Twitter, and like us on Facebook.