Like a villain in a horror movie, the widely debunked concept of terrorist "radicalization" is once again raised from the grave by the Congressional Research Service (CRS) in its 2013 report, "American Jihadist Terrorism: Combating a Complex Threat." CRS is an influential legislative branch agency charged with providing objective policy analysis for members of Congress, which makes its continued reliance on the "radicalization" model promoted in a now-discredited 2007 New York Police Department report, "Radicalization in the West," particularly troublesome.

The NYPD report purported to describe the process that drives previously "unremarkable" people to become terrorists. According to Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly's preface, the document was intended to "to assist policymakers and law enforcement officials, both in Washington and throughout the country by providing a thorough understanding of the kind of threat we face domestically." It theorized a simple four-step process starting with the adoption of a particular set of beliefs to becoming a terrorist, though it strangely conceded that not all terrorists need to go through all, or any of these steps, and that people who did go through the steps would not necessarily become terrorists – though that didn't mean they weren't dangerous. Confused? It gets worse.

The report only examined terrorist acts committed by Muslims, and essentially suggested that all Muslims were potential terrorists that needed to be watched, stating that "[e]nclaves of ethnic populations that are largely Muslim often serve as 'ideological sanctuaries' for the seeds of radical thought." It posited a profile of potential terrorist "candidates" so broad that it's no profile at all: within these "Muslim enclaves," potential terrorists could range from members of middle class families to "successful college students, the unemployed, the second and third generation, new immigrants, petty criminals, and prison parolees." In other words: anyone and everyone. It identified "radicalization incubators," including mosques, as well as "cafes, cab driver hangouts, flophouses, prisons, student associations, nongovernmental organizations, hookah (water pipe) bars, butcher shops and book stores." In other words: any place and every place. Commonplace activities for Muslim-Americans, like wearing Islamic clothing, growing a beard, abstaining from alcohol and joining advocacy organizations or community groups were all listed as potential indicators of radicalization. In other words: any kind of behavior and all kinds of behavior.

If it sounds like the report's description of potential terrorists is so overbroad it could include entire Muslim-American communities, this does not appear to be accidental. Indeed, the report provided the ideological foundation for the NYPD Intelligence Division's program of mass surveillance of Muslim communities throughout the Northeast. Not surprisingly, this poorly focused program "never generated a lead or triggered a terrorism investigation," according to the Associated Press, which received a Pulitzer Prize for its coverage of the NYPD's program.

The NYPD radicalization report was quickly denounced by advocacy and academic organizations for its overstated and flawed facts and serious methodological errors. The NYPD responded by inserting a "Statement of Clarification" in 2009 that made this remarkable claim:

"…this report was not intended to be policy prescriptive for law enforcement. In all of its dealings with Federal, State and Local authorities, the NYPD continues to underscore this important point."

What? In addition to completely contradicting its own preface, the disclaimer refutes the entire purpose of the report. If a police terrorist study isn't intended to impact police counterterrorism policy, what is it for? Is it just a thought experiment?

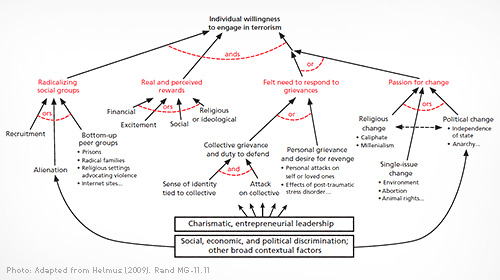

Yet, despite all we know of the admitted shortcomings of the NYPD report, the CRS continues to cling to its model of radicalization, suggesting that individuals can become terrorists "by radicalizing and then adopting violence as a tactic." This concept, that the adoption of a particular belief set is a precursor to violent action is refuted in empirical studies of actual terrorists, like one from RAND, which concludes that an individual's decision to engage in terrorist violence is a complex one involving a matrix of different environmental and individual factors, no one element of which is necessary nor sufficient in every case (see its "Factor Tree for Root Causes of Terrorism" above, which looks a whole lot more complex than the NYPD's four-step process).

In addition to being factually wrong, this radicalization concept is also dangerous, because, as the CRS report points out, adopting beliefs and associating with like-minded people is First Amendment-protected activity. But if counterterrorism officials believe that adopting radical beliefs are a necessary first stage to terrorism, they will obviously target belief communities and activists with their enforcement measures, as they often do. The CRS report highlights the NYPD radicalization theory, and while it acknowledges the criticism of the NYPD report it continues to hew closely to the model of radicalization it promotes. This is particularly true in its discussion of the appropriate law enforcement response to radicalization, in which it describes the "major challenge" as determining "how quickly and at what point individuals move from radicalized beliefs to violence." The faulty assumption that radical thoughts lead to violence drives many of the inappropriate law enforcement actions against Muslim-American communities and political activists that, like the NYPD surveillance program, violate civil rights but don't actually improve security.

It is long past time to euthanize this erroneous and dangerous theory, as many terrorism researches are already suggesting. Moreover, a more recent study from the Triangle Center of North Carolina suggests that recent data reflects a small and declining threat from Muslim-American terrorists, not the "uptick" that CRS reports. And West Point's Combating Terrorism Center issued a revealing study indicating that far-right extremists have engaged in more comparatively violent activity over the last twenty years, which the FBI and policy makers have failed to recognize. Effective counterterrorism policies can't be made from flawed theories and analysis. It is time that CRS heeds the NYPD's recommendation that its radicalization report not be used to drive policy.

Learn more about police practices and other civil liberty issues: Sign up for breaking news alerts, follow us on Twitter, and like us on Facebook.