New Justice Department Documents Show Huge Increase in Warrantless Electronic Surveillance

Justice Department documents released today by the ACLU reveal that federal law enforcement agencies are increasingly monitoring Americans’ electronic communications, and doing so without warrants, sufficient oversight, or meaningful accountability.

The documents, handed over by the government only after months of litigation, are the attorney general’s 2010 and 2011 reports on the use of “pen register” and “trap and trace” surveillance powers. The reports show a dramatic increase in the use of these surveillance tools, which are used to gather information about telephone, email, and other Internet communications. The revelations underscore the importance of regulating and overseeing the government’s surveillance power. (Our original Freedom of Information Act request and our legal complaint are online.)

Pen register and trap and trace devices are powerfully invasive surveillance tools that were, twenty years ago, physical devices that attached to telephone lines in order to covertly record the incoming and outgoing numbers dialed. Today, no special equipment is required to record this information, as interception capabilities are built into phone companies’ call-routing hardware.

Pen register and trap and trace devices now generally refer to the surveillance of information about—rather than the contents of—communications. Pen registers capture outgoing data, while trap and trace devices capture incoming data. This still includes the phone numbers of incoming and outgoing telephone calls and the time, date, and length of those calls. But the government now also uses this authority to intercept the “to” and “from” addresses of email messages, records about instant message conversations, non-content data associated with social networking identities, and at least some information about the websites that you visit (it isn't entirely clear where the government draws the line between the content of a communication and information about a communication when it comes to the addresses of websites).

Electronic Surveillance Is Sharply on the Rise

The reports that we received document an enormous increase in the Justice Department’s use of pen register and trap and trace surveillance. As the chart below shows, between 2009 and 2011 the combined number of original orders for pen registers and trap and trace devices used to spy on phones increased by 60%, from 23,535 in 2009 to 37,616 in 2011.

During that same time period, the number of people whose telephones were the subject of pen register and trap and trace surveillance more than tripled. In fact, more people were subjected to pen register and trap and trace surveillance in the past two years than in the entire previous decade.

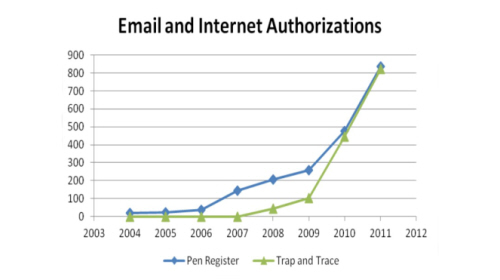

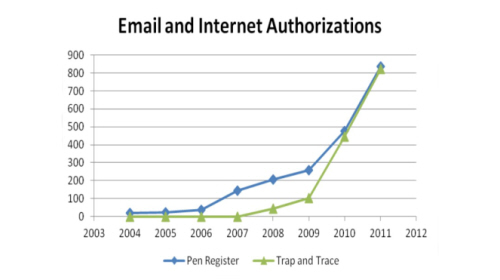

During the past two years, there has also been an increase in the number of pen register and trap and trace orders targeting email and network communications data. While this type of Internet surveillance tool remains relatively rare, its use is increasing exponentially. The number of authorizations the Justice Department received to use these devices on individuals’ email and network data increased 361% between 2009 and 2011.

The sharp increase in the use of pen register and trap and trace orders is the latest example of the skyrocketing spying on Americans’ electronic communications. Earlier this year, the New York Times reported that cellphone carriers received 1.3 million demands for subscriber information in 2011 alone. And an ACLU public records project revealed that police departments around the country large and small engage in cell phone location tracking.

Legal Standards For Pen Register And Trap And Trace Orders Are Too Low

Because these surveillance powers are not used to capture telephone conversations or the bodies of emails, they are classified as “non-content” surveillance tools, as opposed to tools that collect “content,” like wiretaps. This means that the legal standard that law enforcement agencies must meet before using pen registers is lower than it is for wiretaps and other content-collecting technology. Specifically, in order to wiretap an American’s phone, the government must convince a judge that it has sufficient probable cause and that the wiretap is essential to an investigation. But for a pen register, the government need only submit certification to a court stating that it seeks information relevant to an ongoing criminal investigation. As long as it completes this simple procedural requirement, the government may proceed with pen register or trap and trace surveillance, without any judge considering the merits of the request. As one court noted, the judicial role is purely “ministerial in nature.”

The content/non-content distinction from which these starkly different legal requirements arise is based on an erroneous factual premise, specifically that individuals lack a privacy interest in non-content information. This premise is false. Non-content information can still be extremely invasive, revealing who you communicate with in real time and painting a vivid picture of the private details of your life. If reviewing your social networking contacts is sufficient to determine your sexuality, as found in an MIT study a few years ago, think what law enforcement agents could learn about you by having real-time access to whom you email, text, and call. But the low legal standard currently applied to pen register and trap and trace devices allows the government to use these powerful surveillance tools with very little oversight in place to safeguard Americans’ privacy.

Failure to Share These Reports with the Public Frustrates Democratic Oversight

In order to maintain a basic measure of accountability, Congress requires that the attorney general submit annual reports to Congress on the Justice Department’s use of these devices, documenting:

The period of interceptions authorized by each order and the number and duration of any extensions of each order

The specific offenses for which each order was granted

The total number of investigations that involved orders

The total number of facilities (like phones) affected

The district applying for and the person authorizing each order.

As my colleague Chris Soghoian has noted, however, the Justice Department has routinely failed to submit the required reports. In fact, the Justice Department repeatedly failed to submit annual reports to Congress between 2000 and 2008 (submitting them instead as “document dumps” covering four years’ worth of surveillance in 2005 and 2009). The department’s repeated failure to follow the law led the Electronic Privacy Information Center to write a letter of complaint to Senator Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) in 2009.

Unfortunately, even when the Justice Department does turn over the reports, they have disappeared “into a congressional void,” as Professor Paul Schwartz has put it, instead of being released to the public. The reports for 1999-2003 were obtained by the Electronic Frontier Foundation through a FOIA request. Chris Soghoian obtained the 2004-2009 reports through the same process.

When no reports surfaced in 2010 and 2011, the ACLU filed a FOIA request to obtain them. After our request received no response, we filed suit to enforce it.

Although the Justice Department has in the past repeatedly failed to submit the annual reports to Congress, it appears that it has now cleaned up its act. Both the 2010 and 2011 reports were submitted to Congress in compliance with the reporting requirement. Unfortunately, Congress has done nothing at all to inform the public about the federal government's use of these invasive surveillance powers. Rather than publishing the reports online, they appear to have filed them away in an office somewhere on Capitol Hill.

This is unacceptable. Congress introduced the pen register reporting requirement in order to impose some transparency on the government’s use of a powerful surveillance tool. For democracy to function, citizens must have access to information that they need to make informed decisions—information such as how and to what extent the government is spying on their private communications. Our representatives in Congress know this, and created the reporting requirement exactly for this reason.

It shouldn’t take a FOIA lawsuit by the ACLU to force the disclosure of these valuable reports. There is nothing stopping Congress from releasing these reports, and doing so routinely. They could easily be posted online, as the ACLU has done today.

Even though we now have the reports, much remains unknown about how the government is using these surveillance tools. Because the existing reporting requirements apply only to surveillance performed by the Department of Justice, we have no idea of how or to what extent these surveillance powers are being used by other law enforcement agencies, such as the Secret Service, Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or state and local police. As a result, the reports likely reveal only a small portion of the use of this surveillance power.

Congress Should Pass a Law Improving the Reporting Requirements

One member of Congress is attempting to overhaul our deeply flawed electronic surveillance laws. In August, Congressman Jerrold Nadler (D-N.Y.) introduced a bill to amend the Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 to reflect advances in technology that have taken place since the law was passed over twenty-five years ago. One portion of Rep. Nadler’s bill addresses all of the major problems with the current reporting requirements for pen register and trap and trace surveillance. His bill would expand the reporting requirement to apply to all federal agencies, as well as state and local law enforcement. The bill would also shift the responsibility of compiling the reports from the attorney general to the Administrative Office of the United States Courts, which already completes the reporting requirements for the government’s use of wiretaps, and proactively posts those reports on its website each year.

Congressman Nadler's bill is an opportunity to apply meaningful oversight to the government’s rapidly increasing use of a highly invasive surveillance power. These reforms are critical to protect our privacy and maintain an open and transparent government.