Cell phone searches are a common law enforcement tool, but up until now, the public has largely been in the dark regarding how much sensitive information the government can get with this invasive surveillance technique. A document submitted to court in connection with a drug investigation, which we recently discovered, provides a rare inventory of the types of data that federal agents are able to obtain from a seized iPhone using advanced forensic analysis tools. The list, available here, starkly demonstrates just how invasive cell phone searches are—and why law enforcement should be required to obtain a warrant before conducting them.

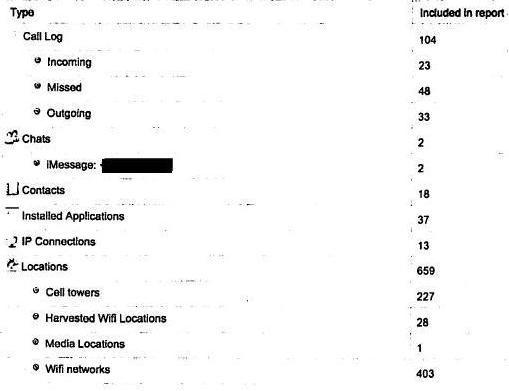

Last fall, officers from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) seized an iPhone from the bedroom of a suspect in a drug investigation. In a single data extraction session, ICE collected a huge array of personal data from the phone. Among other information, ICE obtained:

- call activity

- phone book directory information

- stored voicemails and text messages

- photos and videos

- apps

- eight different passwords

- 659 geolocation points, including 227 cell towers and 403 WiFi networks with which the cell phone had previously connected.

Before the age of smartphones, it was impossible for police to gather this much private information about a person’s communications, historical movements, and private life during an arrest. Our pockets and bags simply aren’t big enough to carry paper records revealing that much data. We would have never carried around several years’ worth of correspondence, for example—but today, five-year-old emails are just a few clicks away using the smartphone in your pocket. The fact that we now carry this much private, sensitive information around with us means that the government is able to get this information, too.

The type of data stored on a smartphone can paint a near-complete picture of even the most private details of someone’s personal life. Call history, voicemails, text messages and photographs can provide a catalogue of how—and with whom—a person spends his or her time, exposing everything from intimate photographs to 2 AM text messages. Web browsing history may include Google searches for Alcoholics Anonymous or local gay bars. Apps can expose what you’re reading and listening to. Location information might uncover a visit to an abortion clinic, a political protest, or a psychiatrist.

In this particular case, ICE obtained a warrant to search the house, and seized the iPhone during that search. They then obtained a second, separate warrant based on probable cause before conducting a detailed search of the phone. However, even though ICE obtained a warrant for this cell phone search, courts are divided about whether a warrant is necessary in these circumstances, and no statute requires one. As a result, there are many circumstances where police contend they do not need a warrant at all, such as searches incident to arrest and at the U.S. border.

The police should not be free to copy the contents of your phone without a warrant absent extraordinary circumstances. However, that is exactly what is happening. Last year in California, for example, Governor Jerry Brown vetoed a common-sense bill that would have required the police to obtain a warrant before searching seized phones, despite the bill’s broad bipartisan support in the state legislature.

Intrusive cell phone searches are becoming ever easier for law enforcement officers to conduct. Companies such as Cellebrite produce portable forensics machines that can download copies of an iPhone’s “existing, hidden, and deleted phone data, including call history, text messages, contacts, images, and geotags” in minutes. This type of equipment, which allows the government to conduct quick, easy phone searches, is widely available to law enforcement agencies—and not just to federal agents.

While the law does not sufficiently protect the private data on smartphones, technology can at least provide some protection. All modern smartphones can be locked with a PIN or password, which can slow down, or in some cases, completely thwart forensic analysis by the police (as well as a phone thief or a prying partner). Make sure to pick a sufficiently long password: a 4 character numeric PIN can be cracked in a few minutes, and the pattern-based unlock screen offered by Android can be bypassed by Google if forced to by the government. Finally, if your mobile operating system offers a disk encryption option (such as with Android 4.0 and above), it is important to turn it on.