The Washington Post reported on Sunday that the District of Columbia is engaging in widespread tracking of citizen’s movements using automated license plate readers (ALPRs). According to the Post, the D.C. police:

• Are running more than one ALPR per square mile;

• Are planning on sharply increasing the density of these devices until they form a “comprehensive dragnet;”

• Retain the time/date/location/tag number even of innocent people for whom nothing is found to be wrong;

• Store that data in a database for three years.

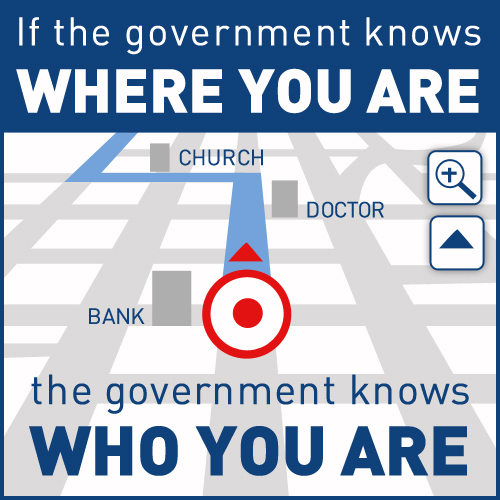

It has now become clear that this technology, if we do not limit its use, will represent a significant step toward the creation of a surveillance society in the United States.

The first we heard of this technology was in a March 2002 piece in The Boston Globe with the headline “Parking Enforcement on a Roll.” At that time, the technology was being deployed to scan parking lots for licenses associated with unpaid parking tickets and other fines. As we said at the time as we began to get questions about the technology, we don’t have any fundamental objections to the technology itself — after all, a police officer could manually phone in all the tags in a parking lot to check for unpaid tickets, and this just did the same thing in a quicker, more efficient way. Sometimes the speed and efficiency of computers does fundamentally change the nature of surveillance compared to non-computerized equivalents — as with GPS tracking, for example. Quantity can change quality. But checking for unpaid tickets and stolen cars does not affect the innocent, so this did not seem to us to be a problem — as long, we said, as the police do not retain location data about innocent people where nothing is found to be wrong.

Our main concern was that the technology not grow into a means for the constant, routine tracking of Americans and their whereabouts. Sometimes when we say things like that, we’re accused of being paranoid. But I am always amazed by the speed and consistency with which our worst fears for these kinds of technologies turn into reality.

Clearly this technology is rapidly approaching the point where it could be used to reconstruct the entire movements of any individual vehicle. As we have argued in the context of GPS tracking (and as I said to the Post reporter) that level of intrusion on private life is something that the police should not be able to engage in without a warrant.

The Post article cites a number of examples in which the technology has proven useful to police. Of course, if the police track all of us all the time, there is no doubt that will help to solve some crimes — just as it would no doubt help solve some crimes if they could read everybody’s e-mail and install cameras in everybody’s homes. But in a free society, we don’t let the police watch over us just because we might do something wrong. That is not the balance struck by our Constitution and is not the balance we should strike in our policymaking.

Finally, technologies that have such significant implications for our privacy — and more broadly, what kind of society we want to live in — should not be put in place through what I call “procurement policymaking.” The police should not be able to run out and buy a new technology and put it in place before anybody realizes what’s going on — before society has a chance to discuss and debate it and consider where we want to draw the lines between police power and the freedom to live a private life. That decision is one that should be made through the full, open, democratic process — not quietly and unilaterally by police departments.