A Creeping Private-Sector “Checkpoint Society”—and a Small Step to Protect Your Privacy

I was at a Target store recently and threw a bottle of wine in my cart to bring as a gift to a party. Later, when I got to the register, the cashier asked to see my ID. That in itself was silly, because it’s safe to say I’m a few years past the point where anyone might mistake me for someone under 21. But whatever; alcohol age-enforcement has gotten bureaucratic beyond all reason.

I held the ID up for her to see. Before I could react, she took my license from my fingers, held it up to a scanner, and BEEP!

Presto: all the information on my license (I had to assume) was flashed into Target Corporation’s computer system. In my state that includes height, weight, sex, date of birth, full legal name, address, driver’s license number, need for corrective lenses, and organ donor status. Some states’ licenses contain even more information. But the only thing the cashier really needed was to see the year of birth on my license—actually, just the last two digits would be enough.

“I didn’t give you permission to do that!” I objected to her. But the deed was done.

At a minimum, this aggressive grabbing of my personal information by Target was just plain rude. It was also a potentially significant invasion of my privacy (more on this issue here and here).

There are a lot of permissionless seizures of our private information taking place these days, but usually they don’t take such a physical form. Target’s privacy policy, unlike many companies’, does address not only their web site but also their offline practices. But (like so many other companies’) it is so broad that it imposes few restrictions on what they do.

Bars, of course, also routinely ask people for their IDs—and the scanning of licenses by some bars has been reported for years. In 2002, the NYT reported that some bars were using data from patrons’ licenses to compile databases for marketing purposes. There are reports of bars in the US and Canada moving toward using this infrastructure to create blacklists of supposed troublemakers (which raises not only privacy but also abuse and due process concerns). European colleagues report that several countries there have made similar moves towards combining ID checks and blacklists in order to block alleged “troublemakers” from traveling to or visiting certain areas. Other private-sector blacklists are also being created. Some retailers, for example, require customers who are returning an item to permit their driver’s licenses to be swiped so that their returns can be tracked and compared against a secret list of individuals who have made too many returns.

Not long after the Target incident, I went to a meeting hosted in a fancy Washington, D.C. law firm building that, judging by its security procedures, apparently thinks it’s #1 on Al Qaeda’s hit list. As in many buildings, the security guard asked to see my ID—standard silly security—and once again, before I could object: BEEP! My license was data-dumped. I never expected this from a building security checkpoint. I was very annoyed, and started to give the guard a piece of my mind, but like the Target cashier, he was of course just following the instructions he’d been given, and there was nothing to be done. So now I have to presume that the security people at some unnamed building management company have all the information on my driver’s license. (The guard claimed the information was not retained but just used to print me out a temporary badge, but I can’t know how much credence to put in that.)

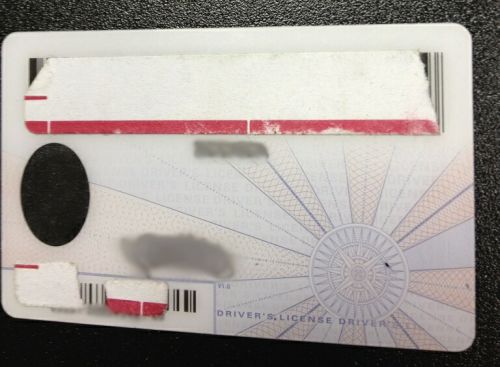

“Enough of this,” I thought, and while I was upstairs in that meeting, I took the very simple step of tearing a strip off my “Hello… my name is” nametag sticker and covering up the barcodes on the back of my driver’s license. Here is a picture of the back of my license:

The back of my driver’s license, with sticker covering bar codes

That should thwart the next person who tries to grab all my ID information without permission. At the very least, I am now able to enter into a negotiation before any swiping takes place. If someone has a need to scan my license that I recognize as legitimate, such as a police officer who has pulled me over for speeding, the sticker is easily removable. (State laws usually ban “altering” a driver’s license, but it would be hard to imagine anyone claiming that placement of a temporary, easily removable sticker on the back surface of one’s license, with no fraudulent intent, could be a violation of such laws. However, any kind of more permanent erasure of a barcode is probably not a good idea.)

Note that a few states, including California, Rhode Island and New Hampshire, have passed laws limiting third-party access to, and retention of, information on driver’s licenses. The American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators has proposed model legislation imposing such restrictions, but it is not clear that many states have adopted it.

There are a couple of broader points to make about this experience.

• First, this is one of those all-too-rare cases in which you can take a simple and direct action to protect a little bit of your privacy, which so often is a matter of social policy over which the individual has little control other than through the democratic political process. There’s not much you can do to prevent records being kept of your comings and goings if you use an electronic toll pass, for example—or, credit cards at Target.

• Second, this incident is a reminder of our need for comprehensive data privacy laws that institute the Fair Information Practices—rules recognized around the world as minimum standards for fair treatment of individuals.

• Finally, there has been talk from time to time about putting RFID chips into driver’s licenses. We have fought for a number of years against the inclusion of RFIDs in identity documents of any kind, not only because of the security concerns they raise, but also because of just the kind of thing I’m talking about here—the potential that stores, restaurants and bars, office buildings, etc., will install devices for routinely reading these IDs, leading to an infrastructure for pervasive tracking—and following that, control (for example, through the use of blacklists to exclude certain people from certain places). Passports and Enhanced Driver’s Licenses used for border crossing in some states such as New York, Vermont, Michigan and Washington, already contain RFID chips, but they are probably not common enough that stores or bars would invest in the infrastructure for reading them – at least so far, that we’ve heard of. It’s bad enough to have someone scan your driver’s license without asking—at least you can take control of that as I have done. It would be far worse if they could do so from across the room without you even knowing, or being able to stop it.

Recently, I went back to Target, and added a bottle of wine to my cart to see how they would handle my new, sticker-sporting license. This time, the cashier was ordered by her computer to get my ID from me because I was buying a bottle of soda—before I’d even taken the wine out of my cart. “This happens a lot,” said the nice cashier, adding that while the soda appeared to be some kind of bug, there were other non-alcohol products that persistently required that the cashiers scan IDs. Internet reports indicate some stores are requiring ID scans for video games sales and even compressed air, for example.

She took my ID and tried to scan it; when it didn’t work she didn’t bat an eye, as apparently it’s routine that some IDs are “non-scannable.” She had to call a supervisor to over-ride her computer’s insistence that she scan an ID.

I called Target to ask them about their policy and they emailed me a statement that said:

Swiping a guest’s ID allows Target to verify the age or identity of guests with a simple process. It also allows Target to control the sale and distribution of restricted products.

When swiping a guest’s ID, Target only retains the data that is relevant to the type of transaction. For example, in the case of your alcohol purchase, only your date of birth was retained with the receipt. Information obtained during the ID swipe is not used for any other purposes.

It is very good to hear that they don’t retain all the data from scanned licenses or use it for other purposes. Though, I don’t see why they have to retain date of birth, which is a powerful piece of information frequently used to uniquely identify a person and disentangle their data from others’.

I am going to leave that sticker on my license.

Companies are in the business of making money, and as long as nobody stops them, they are likely to continue using every stratagem at hand to collect our personal information that is so valuable to them. There are two ways to stop them: A) enacting laws, and B) consumer pressure. The first is vital, and we need to keep working on that, but meanwhile shoppers should take whatever small steps they can to defend their data from grasping hands.