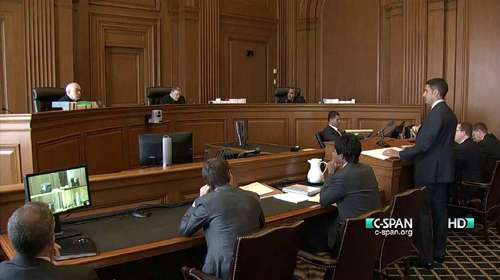

Writing in the New Republic, Yishai Schwartz notes the confluence of two privacy stories yesterday: the theft of celebrities’ private nude photos stored in Apple’s iCloud, and my colleague Alexander Abdo’s argument before the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in our challenge to the NSA’s domestic telephone metadata collection program. Schwartz argues that we and other privacy advocates are misguided to place such focus on the NSA because “the real danger to contemporary privacy isn’t government intrusion at all: It’s the weaknesses of private corporations.”

He writes,

The ACLU portrays a future where the government sweeps up enough data to piece together our most intimate secrets. Federal agents might never have legal access to our nude photos, but our medical conditions, IQ’s, and romantic lives are fast becoming an open book. All it would take would be another Nixon or Hoover to put this data to dastardly uses. Better to leave this data in the hands of the private sector, argue the privacy advocates.

This is misguided, he argues, asking:

Is another Nixon, and particularly one powerful enough to overcome layers of post-Watergate oversight and compliance mechanisms, really more likely than an iCloud or Gmail hacker? When corporations cannot even be relied upon to secure our content, it seems naïve to automatically entrust our privacy to the private sector rather than the government. And it seems odd to allow Verizon commercial access to the same information that we deny the NSA for the purpose of counterterror.

In the modern era, it is the large corporations that pose the greatest threat to privacy. Google, Amazon, and Facebook may know things about us that we have never written in an email or stored in a file. We may never even know what is included in the mosaics of our lives that corporations are already weaving. With the government, we can take comfort that layers of bureaucracy, minimization procedures, and oversight prevent tyranny and mitigates the damage from leaks. But with private corporations, we have no such assurances.

From time to time we hear these kinds of arguments, which convey the message, “when it comes to privacy invasion, companies are far scarier than the government, so all this fuss about the government invading privacy is overblown and it’s the companies we should be paying attention to.” (Occasionally we hear the reverse as well.)

We shouldn’t play this game. Our privacy is under assault from the government and from corporations. We can talk about which threat is “bigger,” but such conversations always threaten to imply that we shouldn’t worry about one threat or the other. At the end of the day there’s no reason we shouldn’t expect our privacy to be protected from both, and work toward that end. We live in a democracy, we are in control of our destiny, and if we want we can protect ourselves from spying by powerful institutions—government and corporate alike—through good public policies.

Not to mention that the distinction between government and corporate assaults on privacy is often a distinction without a difference, as we have been pointing out since at least 2004. The government regularly purchases or requisitions information from private-sector databases—and in some cases orders companies to collect, maintain, and monitor data on its behalf—even while the private sector pushes new data and surveillance products on the government.

The threat that companies pose to privacy is every bit as bad as Schwartz describes, but he significantly understates the privacy threat from government. For example he:

- Confines his discussion of government spying to just one program (telephone metadata collection) of the dozens that have been revealed so far. (None revealed so far involve the secret collection of nude photos, but we know the NSA’s British partner does collect such images.)

- Hinges his argument on acceptance of the artificial and out-of-date distinction between content and metadata.

- Takes internal bureaucratic “oversight and compliance mechanisms” too seriously as meaningful protections of privacy. (Even the limited information we have about the effectiveness of such mechanisms that has leaked out via the FISA Court is non-confidence-inspiring, to say the least.)

- Ignores the long history of government misuse of surveillance powers for political purposes.

- Fails to grapple with the significant fact that the government has the coercive authority to deprive us of life and liberty, something no Silicon Valley giant can ever do.

Finally, Schwartz misdescribes the position of privacy advocates. Our aim isn’t to shift the collection and storage of huge amounts of records about people’s activities from the government to the private sector, as he suggests; we want to stop that kind of data tracking by any institution—or more precisely put such data under the control of the individual.