VIDEO: Yes, Mass Collection of U.S. Phone Records Violates the Constitution

EDITOR'S NOTE: A resounding win! A Philadelphia audience sided squarely with team civil liberties in a debate hosted yesterday by Intelligence Squared. Arguing for the motion, "Mass Collection of U.S. Phone Records Violates the Constitution," were ACLU staff attorney Alex Abdo and Elizabeth Wydra, chief counsel of the Constitutional Accountability Center. They faced off against John Yoo, a former Justice Department attorney known for authoring the Bush-era torture memos, and Stewart Baker, former NSA general counsel.

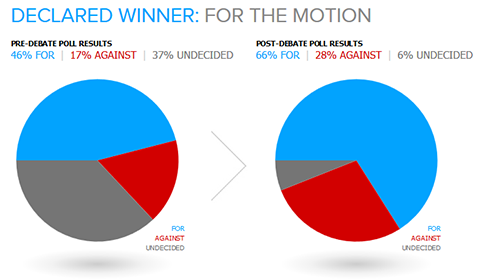

Intelligence Squared debates measure the audience's support for each side both before and after the debate, so the winner isn't just a question of who earned a plurality or a majority of votes, but who compelled more audience members to change their positions. Team civil liberties won on both fronts: 46 percent of the audience voted for the motion (with 17 percent voting against and 37 percent undecided) before the debate. By the end, a full 20 percent became convinced that the NSA's bulk collection of ordinary Americans' phone records is in direct violation of the Fourth Amendment. The debate ended with 66 percent voting for the motion, 28 percent against, and 6 percent undecided.

Read Alex's opening statement below. Or even better, just watch the debate:

I'm honored to be here to discuss the mass collection of Americans' phone records by the NSA. Before getting into that program, though, it's critical to recognize that this debate is not just about phone records, and it is not just about the NSA. This is a debate about the kind of society we want to live in. Do we want to live in a country in which the government routinely spies on hundreds of millions of people who have done absolutely nothing wrong? Or do we want to be true to the vision of our nation's founders, who believed that the government should — as a general matter — leave us alone unless it has cause to invade our privacy. I think our founders got it right, and I hope you'll agree, which is why you should vote for the resolution: Mass collection of our phone records violates the Fourth Amendment.

Here's what it looks like to live in a society of mass surveillance:

Every time you place or receive a call, the government knows who you talked to, when the call started, and how long it lasted. The government knows (1) every time you called your doctor, and which doctor you called; (2) which family members you stay in touch with, and which you don't; and (3) which pastor, rabbi, or imam you talked to, and for how long you spoke.

The government knows whether, how often, and precisely when you called the abortion clinic, the local Alcoholics Anonymous, your psychiatrist, your ex-boyfriend, a criminal-defense attorney, and the suicide hotline.

If you called someone today — by tomorrow morning, the government will have a record of that call. It will keep that record for the next five years. And it is doing the same for every one of your calls, and for every one of the calls of millions of other Americans who have done nothing wrong.

***

This program is the most sweeping surveillance operation ever undertaken in the United States.

And it is unconstitutional for the simple reason that the Fourth Amendment does not permit dragnet surveillance. In fact, as my partner will explain in a few minutes, dragnet or indiscriminate surveillance was the principal evil the Fourth Amendment was designed to prevent.

And for good reason. Dragnet surveillance intrudes on one of the most fundamental of liberties in a free and democratic society — to be left alone by our government absent good cause.

The phone-records program breaks that promise. It places the entire country under surveillance without any suspicion. It threatens our ability to communicate freely without having to worry that the government is looking over our shoulders. It discourages journalists' sources from coming forward, knowing, as they now do, that their every call is being documented in a government database. And it causes ordinary Americans to hesitate before calling individuals or organizations they would rather not have in their permanent record, on file with the NSA.

***

Now, our opponents will attempt to minimize the NSA program's intrusiveness and exaggerate its effectiveness. They will argue (1) that the Fourth Amendment does not protect our phone records; (2) that there are protections in place for our privacy; and (3) that the program is necessary for our national security.

Those arguments are all wrong.

First, our phone records—particularly when they are collected in bulk—are extraordinarily sensitive. They reveal all of your associations: personal, professional, medical . . . all of them. In fact, your phone records can be every bit as sensitive as what you actually say on the phone. If you call someone other than your spouse routinely at 1 in the morning, you don't have to know what's said in order to know what's going on. If a government employee calls a reporter a dozen times before news breaks of an illegal government program, again, the call pattern tells the story. Our phone records are, in other words, a proxy for the content of our calls.

Our opponents will say that the Supreme Court has already decided that phone records are not protected by the Constitution. The argument is based on a Supreme Court case, called Smith v. Maryland, decided in 1979. But that case involved the collection for several days of an individual criminal suspect's phone records. The NSA's program—in contrast—involves the indefinite surveillance of millions of innocent Americans.

Our opponents will say that these differences don't matter, but it's truly bizarre to define the boundaries of privacy in the digital age based on a legal opinion issued before the internet as we know it was created—an opinion that many Supreme Court justices have already said is ill-suited to the digital era.

Second, the privacy protections that our opponents will focus on are a red herring. Those restrictions are weak. They can be violated, and they already have been thousands of times. But more importantly, under our opponents' theory, the Constitution simply does not apply to our phone records. This means that the government could collect them without any of the supposed privacy protections our opponents will describe.

Another fatal flaw with the argument is that the government's collection of our phone records violates our privacy even if there are restrictions on their later use. The collection itself is a violation. For that reason, we don't let the NSA keep a copy of every single email sent in the country, so long as it has protections in place. And we don't allow the NSA to put a video camera in our bedrooms, so long as it agrees not to press play without a good reason.

Third, bulk collection has not made us any safer. Virtually every independent review of the NSA's phone-records program has concluded that it hasn't stopped any terrorist attacks, and that the government can track down terrorists without mass collection, by issuing targeted requests to the phone companies.

A congressional review group said that after carefully studying the NSA's classified evidence, they could not identify "a single instance involving a threat to the United States in which the telephone records program made a concrete difference." A separate presidential review group came to the same conclusion. And the president himself has agreed with both of those reports.

***

One final point. Tonight's resolution is focused on phone records, but don't be fooled—the consequences are much, much broader. If the Fourth Amendment permits the bulk collection of our phone records, then it would permit the bulk collection of other similar records.

The problem is that virtually everything we do today leaves a digital trail of some sort. Whenever you send an email, visit a website, use your credit card, or even just walk around with your phone turned on—you are leaving a rich trail of digital breadcrumbs in your wake.

The arguments our opponents will make tonight would expose all of that information to routine, bulk collection by the government.

That's not the world that our framers envisioned when they drafted the Fourth Amendment, and it's not the world that you should accept. You should vote for the motion: Mass collection of our phone records violates the Fourth Amendment.

Learn more about government surveillance and other civil liberties issues: Sign up for breaking news alerts, follow us on Twitter, and like us on Facebook.