Victory! Court Allows Wikimedia’s Challenge to NSA Surveillance to Go Forward

In a critical victory for privacy and the rule of law, a federal court of appeals ruled unanimously today that an ACLU challenge to NSA internet surveillance, Wikimedia v. NSA, can go forward. As the court explained, Wikimedia, the lead plaintiff in the lawsuit, persuasively argued that its communications are searched by the NSA. As a result, we’re one step closer to ensuring that secret, warrantless spying will be subject to scrutiny in the public courts.

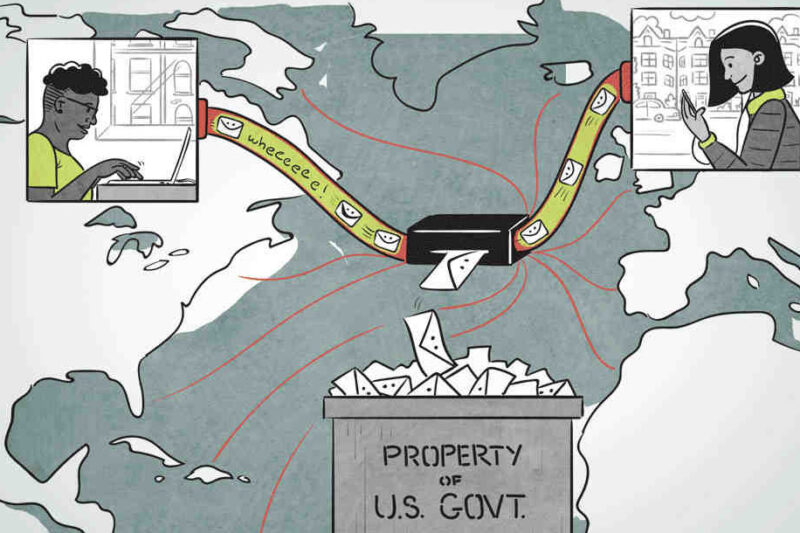

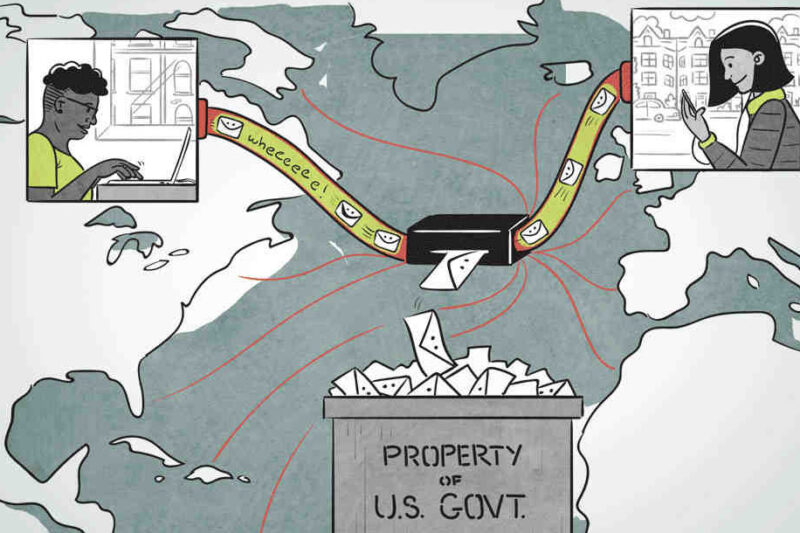

At issue is the NSA’s “Upstream” surveillance, which involves the continuous monitoring of international internet communications. With the help of companies like AT&T and Verizon, the NSA conducts this spying by tapping directly into the internet backbone inside the United States — the physical infrastructure that carries Americans’ emails, online chats, and web browsing. The agency then copies and combs through vast quantities of the international internet traffic whizzing by. And it does all of this without a warrant. (See this comic for a more detailed explanation of how Upstream works.)

The government claims that Upstream surveillance is authorized by Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act. That law allows the NSA to engage in warrantless surveillance of Americans when they are communicating with over 106,000 so-called “targets” abroad. But no judge signs off on these targets, who need only be foreigners abroad likely to communicate “foreign intelligence information,” which is defined incredibly broadly. Targets can include people who have no connection to terrorism and are not accused of any wrongdoing whatsoever, like journalists, lawyers, and human rights researchers.

As a result, the NSA secretly vacuums up millions of communications every year. While the government recently suspended one element of this program — which collected communications about targets, not just to or from them — it continues to scour internet traffic for communications associated with its tens of thousands of targets. Moreover, the government has not disavowed the possibility of reviving “about” collection in the future. The government’s continuing surveillance under Section 702 of FISA is one of the reasons why it’s so important that our challenge to Upstream is going forward.

Three key takeaways from today’s opinion:

1. Wikimedia’s allegations that its communications are subject to Upstream surveillance are “plausible,” not “speculative.”

In October 2015, a federal district court in Maryland dismissed our suit on “standing” grounds, concluding that our clients had not plausibly alleged that their communications were monitored by the NSA. Without standing, none of the plaintiffs would have their day in court to contest Upstream on the merits.

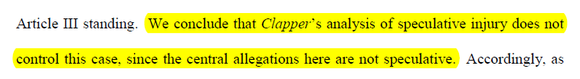

The district court’s opinion relied heavily on the Supreme Court’s decision in a previous ACLU lawsuit, Clapper v. Amnesty International USA, another challenge to warrantless surveillance under Section 702. In February 2013, the Supreme Court dismissed that case, reasoning that the plaintiffs could only “speculate” as to whether they were subject to that surveillance. But as we explained in court, our current challenge to the NSA’s warrantless spying is very different from the last one. Among other reasons, Clapper was decided prior to the Edward Snowden revelations and extensive government disclosures about Upstream surveillance — public disclosures that make it very clear that our plaintiffs’ communications are swept up by the NSA.

The Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals agreed with us with respect to Wikimedia, in part because of the tremendous volume and distribution of Wikimedia’s international internet communications. Rejecting the district court’s analysis, the Fourth Circuit concluded that Wikimedia’s allegations were plausible, not “speculative” within the meaning of Clapper:

In other words:

2. The court wrongly dismissed the other plaintiffs’ allegations as implausible.

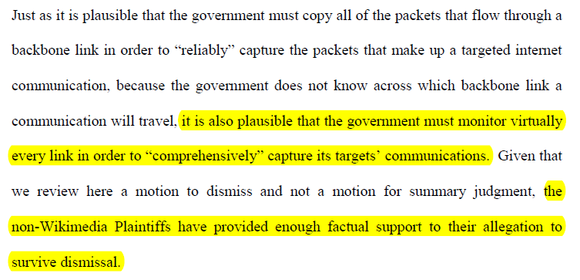

Despite Wikimedia’s victory, two of the three appeals court judges wrongly dismissed the other plaintiffs’ allegations as implausible. In doing so, they failed to consider all of our detailed, well-supported arguments that the NSA is copying and reviewing substantially all international text-based internet communications — including the communications of Human Rights Watch, the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, The Rutherford Institute, and the other plaintiffs.

In a dissenting opinion, Senior Judge Davis succinctly explained why the majority’s “crabbed plausibility analysis” was wrong:

3. Chilling effects matter.

Not only does Upstream surveillance violate our clients’ right to privacy under the Fourth Amendment, but it also violates their First Amendment rights to freedom of expression and freedom of association. The Fourth Circuit acknowledged that Wikimedia’s allegations about First Amendment harms also provide a basis for standing:

Now more than ever, it’s essential that plaintiffs be permitted to challenge unlawful spying in court, so that our judicial system can serve as a bulwark against executive branch overreach. Congress, too, has a role to play. Section 702 is set to expire in December 2017, and the debate around reauthorization of the law is already well underway. The ACLU has called for substantial reforms to Section 702, and we’ll continue to fight to achieve them in both Congress and the courts.