We learned last week that Volkswagen has intentionally programmed the emissions control devices in its diesel cars to detect when an emissions test is underway, and to emit legal amounts of pollution at those times, but to otherwise emit 15 to 35 times as much pollution as the law allows.

We could call those “smart emissions control devices.”

Smartness is in the air. We’re looking at a future of smart cars, smart cities, smart homes, smart electric meters, smart refrigerators, smart televisions, smart watches, and smart who-knows-what-else. If something is “smart,” it must be good, right?

Well, not necessarily. Turns out dumbness has its virtues.

To start with, remember that Lady Justice is blindfolded. There’s a reason we sequester juries to intentionally prevent them from learning certain things. More knowledge does not always lead to more justice or more good. Sometimes where possible we want judges (those grading an essay contest, say, or judging works of art) to be blind to the identities of the people they’re judging.

But let me present an even more basic analogy. When we flip a coin, its dumbness is crucial. It doesn’t know that the visiting team is the massive underdog, that the captain’s sister just died of cancer, and that the coach is at risk of losing his job. It’s the coin’s very dumbness that makes everyone turn to it as a decider. If the coin did know such things, it would bring into question the legitimacy of its “decision.”

Of course a coin can’t “know” anything, but imagine the referee has replaced it with a computer programmed to perform a virtual coin flip. There’s a reason we recoil at that idea. If we were ever to trust a computer with such a task, it would only be after a thorough examination of the computer’s code, mainly to find out whether the computer’s decision is based on “knowledge” of some kind, or whether it is blind as it should be.

Similarly, think about playing a computer game. Let’s take something relatively simple like the classic Tetris. The challenge is to deal with the random shapes that come at you—and the whole game is based on the premise that those shapes are, in fact, random. But how do we know that the programmers haven’t instructed the game to throw easier shapes at us at some points, and harder ones at another? When we’re on a losing streak, and the shapes that we’re getting seem perversely unlucky (as will inevitably happen at some points if the shapes are indeed random), it is easy to question whether there isn’t some perverse intelligence at work behind the scenes—that the game may be watching how we perform and manipulating us to keep our interest high. I find myself increasingly experiencing such thoughts; we might call it “intelligence anxiety.”

The problem with intelligence is that unlike dumbness, it can be evil.

Some games definitely do screw with people. Claw machine games, for example, are programmed to intentionally drop toys a certain percentage of the time (each machine’s operator can actually configure that percentage). And what can be done with relatively simple games such as Tetris and claw machines can be done even more subtly with more complicated software.

The reason we depend on the dumbness of computer games is that in a game of intelligence vs. intelligence, it’s never a fair fight; the game has total control. We just wouldn’t play—at least if the embedded intelligence were apparent to us. The really bad things come when we think something is dumb but it’s not. That’s one reason transparency is so crucial, and will only become more so.

And of course games only highlight the dynamic here; any computerized technology can be programmed to engage in petty nudges or large-scale crimes like Volkswagen’s.

A “smart cities” thought experiment

Another result of intelligence in machines is that it can create resentment and controversy. As an example, let’s think about how that might play out in the “smart cities” context.

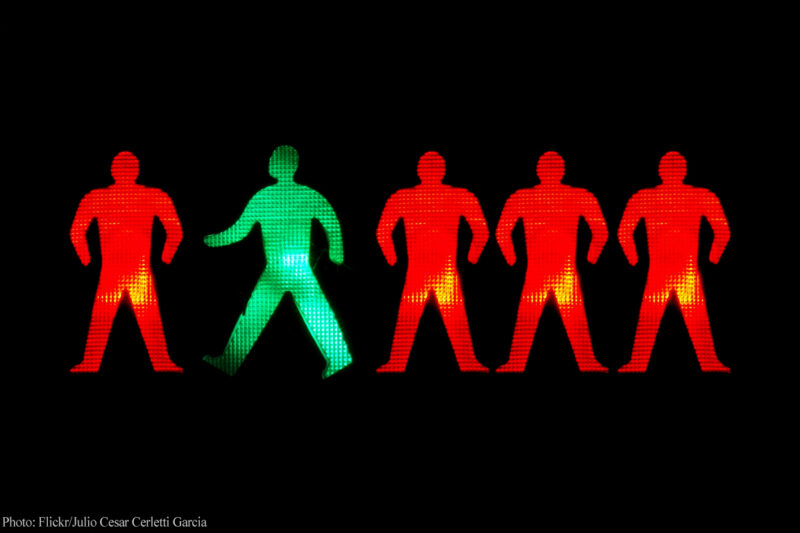

The other day I was sitting in my car at a traffic light. There was no cross-traffic, but the light was red, so I sat there. Then, just as a group of cars finally approached on the cross-road, the light turned green for me, and those cars had to come to a stop. Overall, a very inefficient way of proceeding. How long until our traffic lights are all “smart,” able to watch traffic approaching from different directions and intelligently manipulate the timing of red and green lights for maximum efficiency? Three cars coming from the north, and one coming from the east? Turn it green for the three, make the one wait, right? If the traffic’s backing up from one direction but not another at certain times of day, then extend the green to keep the traffic flowing evenly. That kind of technology could bring significant convenience to drivers, as well as environmental efficiencies from less wasted idling time and fewer accelerations.

However, along with the efficiencies it could also open up a can of worms.

First, issues would arise over the nature of the algorithms. Naturally, like any complicated system, the traffic signal’s “brains” may exhibit bugs and quirks that don’t seem to make sense to drivers. But even putting that aside, judgments will have to be made by the system’s programmers. What if the one car coming from the east is a lot closer to the intersection than the three cars coming from the north? And once our traffic signals are no longer “dumb,” pressures may arise to have them give preference to some cars over others. What if two cars are at equal distances, but one is a small electric car while the other is a big SUV that will require much more fuel to stop and then reaccelerate? Should we reward the driver of the fuel-efficient car, or minimize emissions by giving the SUV the green?

Already we have wireless technology that allows emergency vehicles to turn lights green so they can move through a city more safely and rapidly. This is known as “traffic signal preemption,” and can be integrated into city-wide network management systems, operated from a fire station, or installed as a wireless function on particular vehicles. Aside from the illegal use of such technology by private citizens, that seems like a great innovation—but it’s natural to wonder where its limits are. Presidential motorcades, for example (something we see regularly here in downtown Washington), would seem to be a natural extension of the technology. What about the governor? The mayor when he’s in a hurry? What about prioritizing routes frequented by local residents over routes frequented by visitors or commuters? Or even giving preference to local residents on an individual basis using license plate recognition, or data from transponders? We could even give people (pregnant women, for example) an electronic equivalent of a voucher allowing them to tilt the lights in their favor if they need to rush to the hospital.

To push this scenario even further, I can even imagine an attempt to maximize economic efficiency by making individualized judgments about drivers and the importance of their time. Using license recognition or transponders, technology could easily be integrated into the system, background data about the car’s owner downloaded in a flash, and some basic judgments made about the likely owner’s economic value. After all, is it not ultimately more economically efficient if we make a minimum-wage fast food worker spend an extra two minutes sitting at a red light instead of, say, a brain surgeon or a VP at GiantCorp? Or theoretically the lights could be timed according to the purpose of drivers’ trips, with assessments made by data mining information from a location surveillance system such as a license plate reader network, cell phones, or cameras.

Note that controversies over all these decisions would likely rage even if the system were completely transparent, and purely aimed at optimizing traffic flow. Some drivers, because of the routes they regularly follow, may be worse off than with regular dumb traffic lights, perhaps dramatically so—even though the population as a whole is better off. The losers in the macro optimization process are either going to trust in that overall optimization and its fairness, or they’re going to be mad as hell.

And mathematical transparency (as opposed to transparency over value decisions and of the actual code) may not even be possible. Traffic is a complex system—in the full mathematical sense of the term—and lights are a part of that. If a road is part of a dense city grid with traffic lights on each block, the optimal strategy for timing lights would become very complicated, and it might not even be possible to achieve through the programming of conscious rules; machine deep learning would likely be a much better way to do it. It’s possible that complex timing systems could achieve significant overall increases in the efficiency of traffic—but because it’s a complex system, the timing at particular lights may appear baffling to individual drivers.

Imagine further that the traffic management system is entirely run by a private company that is allowed total control over the algorithms that run this system, and whose decisions (and the value judgments they’re based on) are opaque and not subject to any kind of public input. (We could also imagine that this scenario, instead of applying to vehicular traffic, applies to internet traffic. Suddenly we shift from a futuristic flight of fancy to the very real present-day issue of network neutrality. But I digress.)

I don’t expect most of the above will happen; the point is to accentuate an important dynamic: the smarter a technology gets, the more values decisions must be made, and the more it’s likely to generate controversy and resentment. Our current traffic signals are mostly dumb, and as inefficient as that may be, it is at least perceived as equitable. Imagine a person, running late for something crucial, sitting at a seemingly interminable red light getting tense and angry. Today he may rail at his bad luck and at the universe, but in the future he will feel he’s the victim of a mind—and of whatever political entities are responsible for the shape of that signal’s logic.

Algorithmic objectivity

At work here is what has been called “the promise of algorithmic objectivity.” Algorithms become the latest way to claim something is “natural” (and therefore beyond the political realm) in order to insulate power from accountability. When things are truly dumb, that objectivity can be real, but as machines get smarter and their operation less clear, they become more susceptible to accusations of bias of one kind or another.

The promise of algorithmic objectivity is especially likely to be touted when a computer replaces something controversial that was previously done by humans. The computer is sold as more objective precisely because it’s dumber than the humans. But when dumb things get smarter, they enter the same zone of controversy and contention from the other direction. Either way we get debates between those claiming that a machine is objective and fair, and others claiming—or speculating, if the machine isn’t transparent—that it is not. Or, both sides arguing over just how the machine’s bias should tilt.

(This dynamic is parallel to complaints by leftist political economists that the capitalist system poses as neutral, natural, and objective, while actually being an ideological construct designed to serve certain interests over others. Jurgen Habermas argued in the early 1970s that the legitimacy of modern capitalism was being thrown into crisis partly because the state was increasingly getting sucked into managing the economy, stripping away the shield of objectivity provided by a supposedly neutral marketplace.)

We can see the dynamic at work with Google’s search algorithms. In response to both demands for censorship and accusations of self-advantaging (and allegedly anti-trust violating) biased search results, Google seeks refuge from regulatory pressures by protesting that its algorithms are objective.

Another example is raised by a museum exhibit and Intercept article asking the fascinating question, “when is a photograph ‘real’ and when is it ‘altered’?” The Intercept cites an award-winning image of a Gaza City funeral procession, which was challenged due to manual adjustments the photographer made to its tone. I suspect that if the adjustments had been made automatically by his camera (being today little more than a specialized computer), the photo would not have been questioned. But because there was intelligence and intentionality behind the changes that are made, it is seen by some as “altered.”

The main points I’m driving at here are that first, smartness is not automatically better than dumbness, and in many cases we actually count on things being dumb; and second, political controversies will increasingly swirl around the existence and nature of the intelligence built into our world.

And perhaps most importantly, the growth of intelligence anxiety and all these other dynamics will make transparency more important than ever. If Congress had required (as I’ve argued it should) that all code in all vehicles licensed to travel on public roadways be transparent, Volkswagen would not have gotten away with evading clean air protections for more than half a decade.

Update:

This post was updated to replace the term “neutrality anxiety” with “intelligence anxiety.”