An Apology May Seem Like a Small Thing After Being Tortured. It’s Anything But.

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights will hold a hearing on Friday, October 23, to address the implications of impunity for CIA torture and the need for reparations for victims. In advance of the hearing, an American survivor of torture at the hands of the Brazilian government in 1974 shares his story.

In 2008, while living in retirement in Panamá, I received an email from the Brazilian government. The message invited me to appear the following month before the country’s Amnesty Commission, which grants reparations to people who faced persecution by the government of Brazil between 1946 and 1988.

When I arrived, the president of the commission, Dr. Paulo Abrão, stood up before an audience of some 200 people and said the words I had been waiting more than 40 years to hear.

“Reverend Morris, on behalf of the government of Brasil, I want to ask for your forgiveness for what was done to you by agents of our government 34 years ago.” As a gesture of his government’s repentance, I was awarded a cash gift of some $125,000 and a lifetime pension of approximately $1,000 per month.

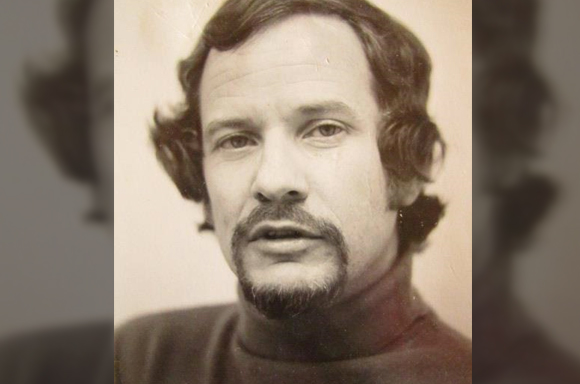

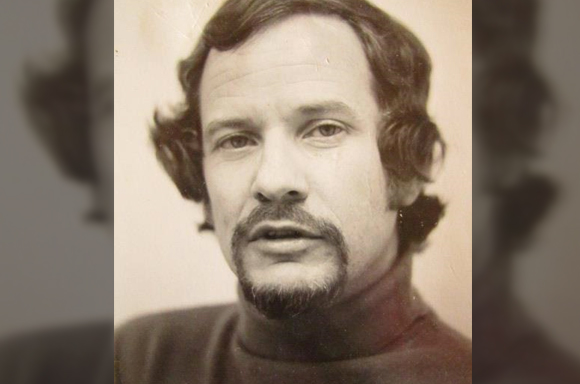

I cannot express how meaningful this experience was. For more than 50 years, I have served as a minister of the United Methodist Church. At the beginning of 1964, I was sent to Brazil as a missionary. A short time later, before I even had any grasp of Portuguese, a CIA-orchestrated coup installed a brutal military dictatorship that would last for two decades.

For the next 11 years, I would serve the Brazilian Methodist Church as a pastor in various locations around the country. In 1970, I was assigned to work with Archbishop Dom Hélder Câmara. The military regime had its sights set on Dom Hélder, who was known to the government for his displeasure with the junta. Starting in 1969, the government began kidnapping and torturing people associated with the archbishop.

I was one of them. On September 30, 1974, because of my close relationship with Dom Hélder, I was kidnapped by the security forces of the Brazilian military and spent the next 17 days in their torture chambers. My torturers beat and electrocuted me. They kept me sleep deprived and in solitary confinement, and they subjected me to a mock staged execution. Many of the torture methods used on me were identical to those used at Abu Grahib in Iraq.

One of my torturers, Major Maia, bragged to me about being a graduate of the School of the Americas, a U.S. Army institution that trained some of Latin America’s most notorious dictators. He told me he was a Christian, fighting with the U.S. against “godless communism.” At one point, he offered me “rehabilitation” if I would confess to being a CIA agent infiltrating Don Hélder’s activities.

Because of the active intervention of various U.S. diplomats and friends, I was released after 17 days and deported from Brazil. A wave of media interest in my story followed, and a letter-writing campaign by thousands of Methodists and human rights activists led to Congress suspending all military assistance to Brazil in 1976.

But the legacy of my experience in Brazil was far from over. Yes, I had my freedom, but I also faced difficulty finding employment in my own country. I moved to Costa Rica, where I established my own construction company. Even then, I couldn’t put the past fully behind me. For years, I was under the watch of Costa Rican security forces, and, I believe, the CIA. My telephones were tapped and my offices were broken into. I was regularly detained at the San Jose airport. My wife was also harassed by security agents, until they learned she was the private secretary of the president of Costa Rica.

My reputation suffered as well, due to the Brazilian Army’s unfounded accusations that I was a Communist on the one hand and a CIA agent on the other. (In the 1970s, those kinds of accusations were like a kiss of death.) My own church briefly rejected me, something that caused me even more pain than the actual torture I had faced. I was also prevented regular contact with my children, who had remained with their mother in Brazil.

Those 17 days in a Brazilian prison in the 1970s affected every day that followed. While the Brazilian government must go further in facing the crimes of the past — including by prosecuting those responsible for atrocities — the importance of its act of repentance toward me and toward other victims cannot be overstated.

Members of my government intervened when I needed them, and saved my life. For this I am eternally grateful. But this is the same government that recently committed the very crimes that I am denouncing here. I hope 40 years don’t pass before our leaders recognize what they have done to their victims, and what those victims need in order to heal.

We should all demand that those in our government who authorized and carried out acts of torture be criminally investigated and held accountable. And for the victims of these crimes to carry on with their lives, our government should pay reparations for the harm done to them.

In 1974, more than 100 members of Congress were United Methodists. I have no doubt that this fact helped save my life when word got out that a United Methodist missionary had been kidnapped and was being tortured in Brazil.

Methodist or not, we must stand up for all torture victims. Torture brutalizes and dehumanizes those who are tortured, but we are all responsible and we cannot remain indifferent. If we don’t hold the torturers to account, we are entrenching a norm that allows torture to go unpunished. This is a terrible blow to all citizens and to humanity as a whole.

Only through accountability can we rejoin the community of nations.