The ‘Magna Carta’ of Cyberspace Turns 20: An Interview With the ACLU Lawyer Who Helped Save the Internet

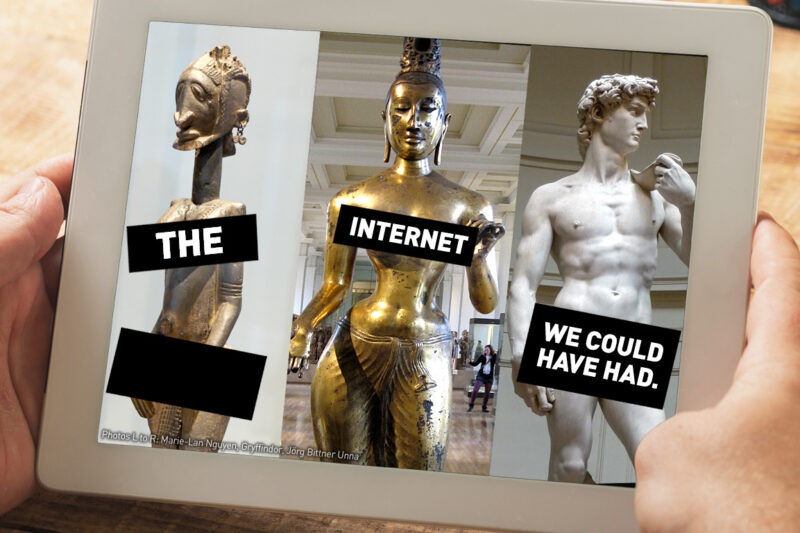

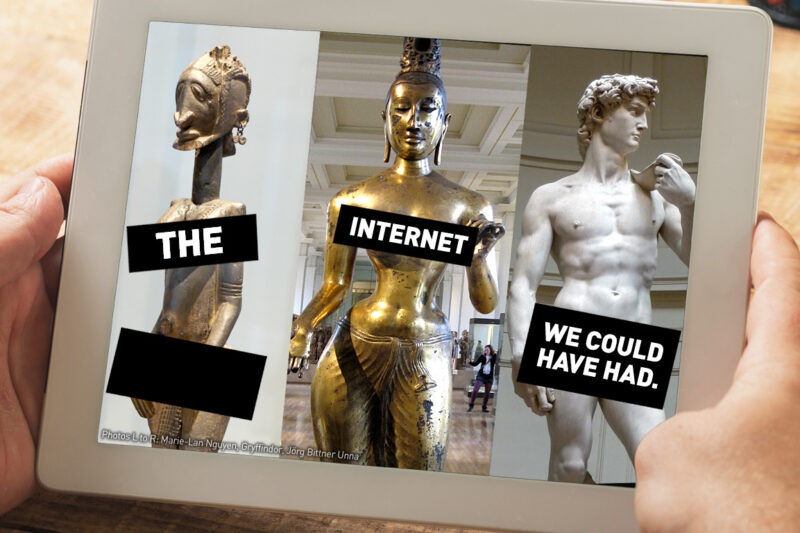

In the mid-1990s, as average American households were increasingly getting online, a “Great Internet Sex Panic” threatened to severely restrict the most significant communications medium of our time.

The Communications Decency Act was introduced in Congress in 1995 to address the fabricated threat that pornography was taking over the web and imperiling our children. “The information superhighway should not become a red light district,” declared Sen. James Exon (D-Neb.), the bill’s sponsor. His solution was to criminalize the dissemination of “obscene or indecent” online content if it could be viewed by minors — essentially, applying the same standards to the internet as those imposed on broadcast television. The bill passed both chambers and was signed into law by Bill Clinton in February 1996.

At the time, the ACLU didn’t even have a website. But recognizing the extraordinary potential of the internet as a forum for the exchange of ideas — one with "no parallel in the history of human communication” — the organization moved to challenge the law. The ACLU represented 20 diverse plaintiffs in the case, including advocacy groups like Planned Parenthood, who feared prosecution over their sexual education materials. We were also a named plaintiff in the case. (Read on to learn why.)

The case made its way up to the Supreme Court, which unanimously struck down the anti-indecency portions of the law on June 26, 1997. Justice John Paul Stevens wrote:

The record demonstrates that the growth of the Internet has been and continues to be phenomenal. As a matter of constitutional tradition, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, we presume that governmental regulation of the content of speech is more likely to interfere with the free exchange of ideas than to encourage it. The interest in encouraging freedom of expression in a democratic society outweighs any theoretical but unproven benefit of censorship.

On the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the decision, often referred to as the “Magna Carta” of the internet, I asked Chris Hansen, who led the ACLU’s lawsuit against the CDA, about what it was like to litigate Reno v. ACLU.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

First things first, can you explain what constitutes indecency or obscenity, and who has the authority to decide if something is indecent or obscene? Has this definition changed over time? And is there a separate category of speech that may be indecent or obscene only for minors?

%3Ciframe%20allowfullscreen%3D%22%22%20frameborder%3D%220%22%20height%3D%22326%22%20src%3D%22https%3A%2F%2Fwww.youtube.com%2Fembed%2FkyBH5oNQOS0%3Fecver%3D1%26autoplay%3D1%26version%3D3%22%20thumb%3D%22%2Ffiles%2Fyt_carlin-580x326.jpg%22%20width%3D%22580%22%3E%3C%2Fiframe%3E

Privacy statement. This embed will serve content from youtube.com.

Laws prohibiting speech about sex date back to the early 1800s. “Obscenity” and “harmful to minors” are terms found in criminal laws that have evolved over time. “Indecency” is a term adopted by the FCC and allows an administrative fine against broadcasters. The CDA made it a crime to engage in speech online that was indecent.

It is virtually impossible to identify speech that fits these categories. During the various internet censorship cases the ACLU brought, we asked the government to identify speech in each category, and they were largely unable to do so. For example, they said that an online photo on Playboy’s website of a topless woman was not harmful to minors, but a virtually identical photo on Penthouse’s website was. In addition, because the standards are subjective, material considered obscene decades ago, like Henry Miller’s “Tropic of Cancer,” is no longer considered obscene. Today very few obscenity cases are bought in either federal or state courts.

Not surprisingly we found that English has more than seven words that some might consider indecent, and all of those words appeared on our website.

In order to challenge the anti-indecency provision of the Communications Decency Act as a plaintiff, the ACLU needed to prove the organization could be prosecuted under that law. That meant it needed to have published online content that might be deemed “indecent” or “obscene.” I’ve heard that we posted pornography on our website in order clear that hurdle. Is that true?

The ACLU wanted to be a plaintiff as well as representing plaintiffs so that history would remember the fight as an ACLU fight. We wanted the case to be called ACLU v. Reno. To sue, we needed to have standing. In other words, we needed a credible argument that we could be prosecuted under the law. At the time, nothing on our website was even arguably indecent.

We decided to do two things. First, the Supreme Court had declared the George Carlin monologue indecent [see video above], and their opinion included the entire monologue as an appendix. So we put the opinion with the appendix on the website. We were afraid that was too cute, so we also held a contest, inviting people who came to our website to post guesses, before they read the opinion, what the seven dirty words were. Not surprisingly we found that English has more than seven words that some might consider indecent, and all of those words appeared on our website. The government never seriously challenged our standing.

Parenthetically, “pornography” is not a legal term. Nothing we had on our site was close to what most would consider pornography.

The web was so new when Congress passed the CDA in 1996 — if I’m not mistaken, we created our website specifically so that we could challenge the law. You needed to argue about the future of the internet to judges who had never used it before. How did you do that? Did either side have a sense of how big the internet would eventually become?

When we decided to bring the case, none of us had been online, and the ACLU did not have a website. We flew down to Washington so that someone we knew could show us the internet. When we litigated the case in Philadelphia, we used a phone line to set up the internet in the courtroom and show the judges what a website looked like. We made an effort to show them websites we thought they would find interesting. We also showed them chat rooms and bulletin boards and the WELL, an early social media site. I’m told that when we argued the case in the Supreme Court, only one of the justices had ever been online and that several others were taken down to the court basement by their clerks and shown the internet.

This is what the ACLU homepage looked like in June 1997.

Both sides knew that the standards that would be applied to a new communications form were incredibly important. We wanted to be sure the internet had the same strong First Amendment standards as books, not the weaker standards of broadcast television. Nevertheless, I don’t think any of us knew how important it would become. In fact, one of our witnesses testified that “If you think you can predict what the internet will become, you’re wrong.” I proposed we drop testimony about the WELL — the social media site — on the grounds that the internet was about the static websites, not social media platforms where people communicate with each other. I was persuaded not to do that, and since I was monumentally wrong, I’m glad I was persuaded.

I’ve heard you explain that in searching for plaintiffs, the ACLU looked for groups that posted content that was sexual enough that it was at risk under the law, but not so sexual that the court wouldn’t want to protect it. That’s how we ended up, for example, with Planned Parenthood as a plaintiff, but not a pornography website. But is it possible to protect one without protecting the other?

Then-ACLU lawyer Ann Beeson spent an enormous amount of time finding sites that were at risk under the law but that judges would not want to see go to jail. If the case was seen as being about protecting Penthouse’s pictures of naked women, we thought we’d lose. So we ended up with 20 sites, like Stop Prison Rape (describing rape in jails and prisons) or the Safer Sex Web page (sex advice for the disability community) or Wildcat Press (a gay and lesbian publisher) that included very frank language about sex that most judges would find valuable. During a later stage internet censorship case, we had about 20 summer law students try to find such sites that could be potential plaintiffs. They loved the assignment for about an hour, but because the assignment inevitably took them to less savory sexually explicit sites, thereafter they complained bitterly.

Because the definitions are so subjective, it is not possible to prosecute these laws without at least risking valuable speech. For example, what some people find “prurient” others may not find “prurient.” “Contemporary community standards” change over time and based on geography. What is “patently offensive” in Meridian, Mississippi, may not be “patently offensive” in New York City. If a site is engaged in speech that is close to the line, even if they think it is valuable, they are likely to self-censor to avoid any risk of prosecution.

ACLU lawyers at a press conference after the decision in Reno v. ACLU. (Left: Chris Hansen; right: Chris Hansen and Ann Beeson)

Our victory in Reno determined that the internet would enjoy the broadest of First Amendment protections — like those accorded to books. That’s as opposed to broadcast television, where speech the government considers indecent or obscene is prohibited. How do you explain this distinction? Do you think it makes sense?

As the government increasingly pressures companies to remove online content, we’re creating a censorship system that applies to an enormous amount of communications that don’t enjoy constitutional protections.

I think most people understand the desire to protect children from adult speech. That’s what motivates laws like these. But both of the internet censorship statutes required the entire internet to be child friendly, even if the effect was to prevent adults from accessing material that they were unquestionably entitled to view. For those parents who want to restrict their children from seeing adult speech, many other alternatives — such as putting the computer in a public area of the home or monitoring usage or blocking software — exist.

The question of different standards for broadcast TV than for books or even cable TV makes no sense at all and will eventually disappear. We were seriously afraid that the broadcast TV model would be applied to the internet because it, like television, comes into the house on a screen in a box, and you don’t always know what you will see when you click. But ACLU v. Reno and the ubiquity of the internet will lead to the demise of the special rules for broadcast TV.

The CDA had various descendants because Congress never gave up trying to prohibit certain kinds of content online. We lost our challenge to the Children's Internet Protection Act (CIPA), which requires libraries and schools that receive federal funding to use filters to block sexually explicit content. Later, the Child Online Protection Act (COPA) attempted to resurrect many components of the CDA but never took effect thanks in part to our litigation. What’s the latest front in the attempt to scrub the internet of sex?

Obscenity is still illegal on the web, but prosecutors rarely bring those cases anymore, partially because of shifting social standards.

I think the greater censorship dangers today involve attempts by nongovernmental entities — such as Facebook, Twitter, Google, and other internet companies — to decide what speech is appropriate online, and those efforts largely are directed at hate speech. Facebook and other internet companies aren’t bound by the First Amendment, which only applies to the government. As the government increasingly pressures companies to remove online content, we’re creating a censorship system that applies to an enormous amount of communications that don’t enjoy constitutional protections.