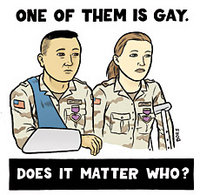

The New York Times‘ “At War” blog on Monday released the stories of seven current and former service members and their experiences in the military under the discriminatory and counterproductive “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” (DADT) policy. You would be very hard-pressed to read these powerful testimonials from obviously outstanding members of the armed forces and not come away with the impression that DADT has undermined and weakened our military, and destroyed very promising careers.

A lesbian combat engineer lieutenant and West Point graduate, currently preparing for a combat deployment to Afghanistan, writes:

The problems encountered are endless. How does a young gay N.C.O. live with his partner when he is forced to live in the barracks because the Army does not recognize his marriage?

How can a soldier receive emergency leave for a spouse who does not exist, according to the Army? How is it possible to incorporate your partner into family readiness groups while deployed?

At a fundamental level, the Army is built around the team, whether it’s a squad, platoon, or even a family readiness group. It’s not a job meant to be done alone. Yet any of these soldiers can tell you that life as a gay service member is a lonely and foreign endeavor in which the typical choice is between having a healthy relationship or family, or pursuing the career you love.

What is gained by forcing otherwise dedicated men and women into making such a choice? This is a question that DADT proponents must answer.

Matthew Rowe, a 2004 graduate of West Point and a former captain in the Army who resigned his commission in 2009, writes:

I would go out on the weekends with my friends and go through the motions of trying to pick up girls and go to clubs, but I would come home feeling more alone and isolated as a result. There were times that I came home after a long day at work, and I felt very alone, ashamed of myself because I couldn’t be “normal,” and depressed that my youth was slipping away and that I wouldn’t experience love while I remained in the Army.

I was not suicidal, but there were some dark days when I wondered what it would be like if I decided that I didn’t want to live any more. Being gay in the military under “don’t ask, don’t tell” really is a private hell. The psychological effect of feeling alone and depressed was more damaging to me than any emotional effect of being shot at or a bomb blast (both of which I have also experienced). The only thing worse for me was the loss of one of my soldiers.

Reading Rowe’s account, I was reminded of the testimony of Adm. Michael Mullen, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, from earlier this year in which he said, “…we have in place a policy that forces young men and women to lie about who they are in order to defend their fellow citizens. For me, personally, it comes down to integrity — theirs as individuals and ours as an institution.”

It is long overdue to end this discriminatory and counterproductive policy which has served to undermine the military and is a disservice to the millions of men and women who serve in it with pride and distinction.