White House-Led Effort to Create Online ID Standards Proceeding; Stakeholders Gather in Phoenix

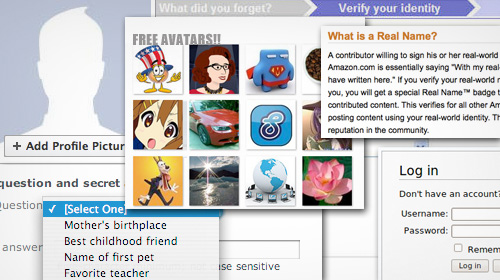

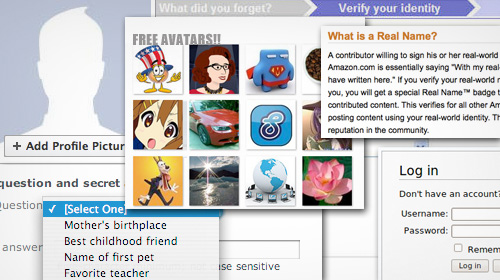

In April 2011, the White House set forth a proposed "National Strategy for Trusted Identities in Cyberspace," or NSTIC. The document was a proposal to create a mechanism by which people could identify themselves online to another party with certainty—a long-elusive goal that has been talked about and pursued by the private sector and "identity community" for many years, without success.

I explained my initial take on this proposal in this January 2011 blog post, and little has changed. In brief, the creation of a rigorous online identity system, even though it is not envisioned as being government-run, has a very real potential to become a de facto mandatory online national ID and to eviscerate online anonymity, which has been such an important part of the internet's vibrancy. On the other hand, such a tool could have good applications, and if the administration's vision does not take hold, there is a strong chance that Facebook Connect or some other private sector alternative may fill the gap—and without any of the privacy protections that the administration has consistently said should be part of this system. Amazing new cryptographic privacy techniques have been developed that, if incorporated into an identity system, would not only be better than what private-sector alternatives are likely to generate, but conceivably could be better than what now exists.

The bottom line is that if everything is done perfectly, an online identity system could be a good thing.

Otherwise, it's likely to be a disaster.

The administration has launched one of its "multi-stakeholder processes" to attempt to create actual concrete proposals and standards for this online identity "ecosystem" (it is envisioned as being made up of a variety of private parties operating under shared standards, not a single centralized government or private operator).

As I have noted before, this concept of a multi-stakeholder process is the ultimate expression of an interest group liberalism theory of government, in which the sum total of all the vectors of private interests produces the public good. But there's no particular reason to believe that that will be the case. In theory it sounds good to get all interested parties together in a room and let them hammer out a compromise solution that works for all of them. There are, however, several problems with this:

- It requires enormous time and resources to fully participate in this process. Stakeholders are now gathered in Phoenix for a third multi-day meeting, and the process has consumed countless other hours of participants' time in meetings of numerous committees—and up to this meeting has really only so far addressed procedural questions about the ground rules.

- The outcome of such a process may be heavily dependent on who shows up, and in what numbers. The NSTIC process is open to all, and the corporate sector makes up a very large proportion of the participants (I don't know exactly how large). Companies can afford to devote personnel and other resources that pose much more significant burdens on nonprofit public interest groups. (That said, the interests of the corporations represented do vary, and many individual corporate representatives are very thoughtful about privacy issues.)

- There is an overarching public interest that may not be adequately or proportionately represented by the powerful interest groups that are able to participate in such a process.

- Sometimes, conflicting interests just can't be squared. When different stakeholders' interests are diametrically opposed, there is nothing magic about getting representatives of those interests together in a room. Their desires may still be zero-sum.

An extended, cumbersome, time-consuming process for trying to hammer out solutions to highly contentious issues is also, one suspects, the perfect refuge for politicians who (as is so often the case due to the nature of their job) are trying to please all sides in a dispute and delay being forced to take sides. It may be a new variation on the old political fudging tactic: "when in doubt, create a commission."

All that said, a multi-stakeholder process may be a somewhat natural fit in this case. Since we don't want the government running an online identity system, and any successful identity network will have to consist of a broad ecosystem with multiple providers rather than a narrow system run by one company, it does makes sense to figure out what kind of proposal will fit with enough diverse parties' interests to be a real, viable thing. Nevertheless, many of the problems I list above appear to apply. At the same time, the administration seems to recognize this fact, and has done a good job in helping shape the process to compensate. For example, the process includes a privacy committee (which I am on) that has special powers to review work product. (Of course, the privacy committee is itself open to all).

I am in Phoenix this week for the third plenary meeting of the Identity Ecosystem Steering Group, or IDESG, as the multi-stakeholder group is called. The group is finally moving beyond process issues, and actually begin trying to build a proposal. Although as I've said we are deeply concerned about this project of creating an online identity system, we are engaging in the process because if it is done right it could be neutral—or just possibly even a plus—for online freedom. Stay tuned!

Learn more about online privacy and other civil liberty issues: Sign up for breaking news alerts, follow us on Twitter, and like us on Facebook.