Discretionary Detention by the Numbers

Overview

Cesar Matias, a gay man, fled persecution in Honduras on account of his sexuality and arrived in the United States in 2005. After living in Los Angeles for seven years, Cesar was convicted of drug possession and was arrested by Immigration and Customs Enforcement in 2012. Months later, he received a bond hearing before an immigration judge, where the judge found that Cesar was not a flight risk nor danger to the community and set a $3,000 bond for his release. But, the judge never asked Cesar whether he could afford that amount.

Since 2016, 9,188 people have been locked up in our immigration system for over 30 days despite having been granted bond, most often because they could not afford to pay it. Like Cesar, most of them are immigrants seeking asylum. They are not convicted of crimes or subject to immediate deportation – in these cases, ICE had a choice, and it chose to imprison them.

In federal and many state criminal bail systems, established procedures require judges to consider a defendant’s ability to pay a bond. Sadly, such protections do not exist for immigrants locked up in ICE detention centers, resulting in wealth-based detention. People should not be locked up simply because they can’t afford their bond.

The Fight Against Discretionary Detention

In April 2016, the ACLU filed a class-action lawsuit in Los Angeles, seeking to require the government to consider ability to pay when it sets bail bonds for immigrants. The suit succeeded. Cesar, our lead plaintiff, was ultimately released from detention, and in a major legal victory, a federal appeals court required for the first time that immigration authorities consider people’s financial circumstances when setting bond as well as their eligibility for release on alternative conditions of supervision.

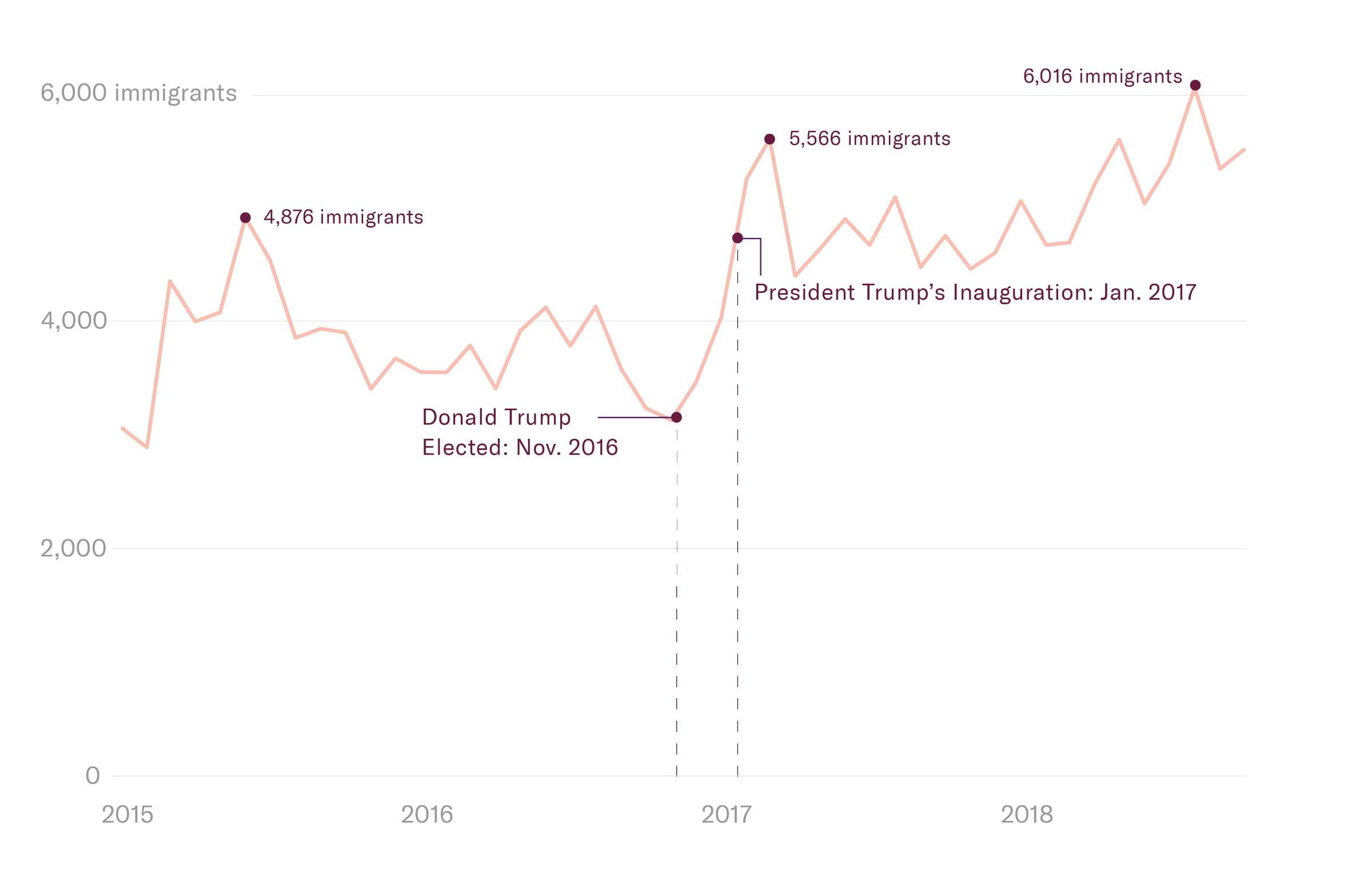

However, these protections only extend to the people within the jurisdiction of one of the twelve regional U.S. appeals courts, and the majority of the country lags far behind. Since taking office, the Trump administration has dramatically increased the use of immigration detention, with the detained population reaching record highs. This blanket increase is happening to people in all different immigration circumstances – including those eligible for release on bond or other conditions of supervision. Since most immigration courts do not require immigration judges to consider someone’s finances before setting bond amounts or alternatives to bond, advocates have predicted that more and more people will receive a bond they cannot afford.

A new ACLU analysis of data from the Department of Justice’s Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) suggests that ICE is indeed detaining more and more immigrants who may have previously been released, making the arbitrariness of the immigration bond system an even more important problem.

Discretionary detention is on the rise

Number of immigrants eligible for a bond between Jan. 2015 and Dec. 2018, by month

While the Obama administration provided clear guidance to prioritize certain groups of immigrants – people with serious criminal convictions and recent arrivals – Donald Trump ran on an anti-immigrant agenda that included a promise to reverse the Obama enforcement priorities. And, once he took office, his ICE chief bluntly told Congress that “No population is off the table.” These were not idle threats; the Trump administration dramatically increased the use of discretionary immigration detention, locking up thousands of people who were previously not a priority.

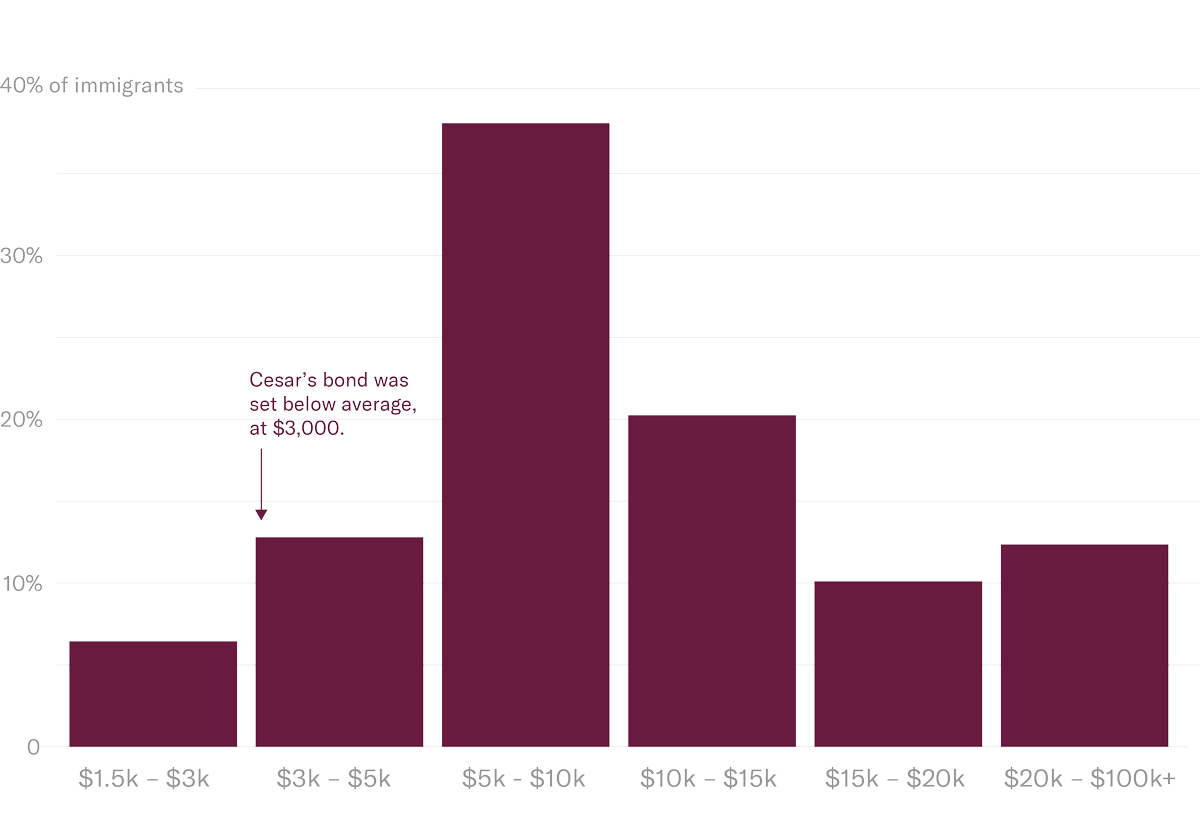

Many people can't afford their bond

As ICE’s detention population grows, so does the number of immigrants given bonds. Unfortunately, since the majority of immigration judges are not required to consider affordability when setting the bond amount, this increase means that more people are receiving bonds that they cannot pay.

Distribution of Unpaid Bond Amounts

Most immigrants since 2016 that couldn't pay their bond for at least 30 days were assigned a bond amount between $5,000 and $10,000

Since 2016, 38 percent of bonds that immigrants did not pay within a month were set between $5,000 to $10,000 dollars. But, as Mr. Matias’s case illustrates, lower amounts may be too high for many. Comparing this with an average American’s savings puts that number in perspective – the Federal Reserve estimated in 2017 that 4 of 10 American adults could not come up with $400 to cover an emergency expense.

Some of those who cannot pay are able to cobble together money from friends and family, but only after spending days, months, or even years in jail – without work, and separated from family and children. The inability to pay bond for can push families into poverty, potentially putting individuals at risk of losing housing, small businesses, or even the custody of their children.

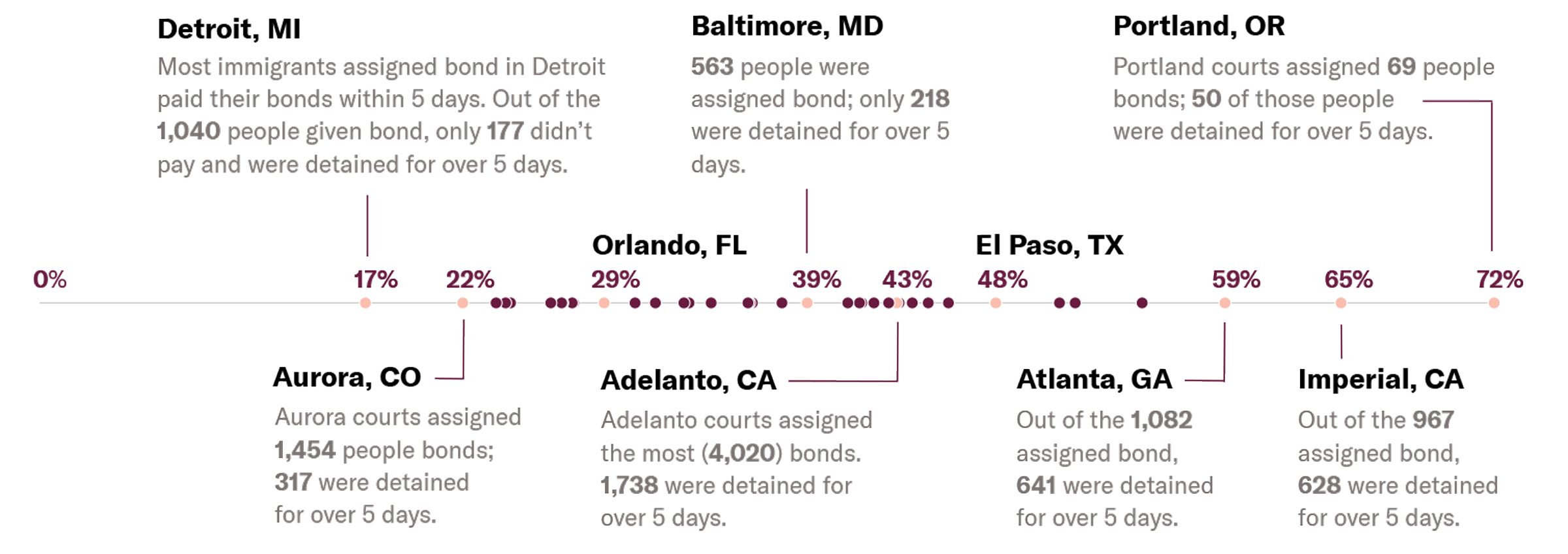

Bond practices are inconsistent and arbitrary

We won the court battle to beat back unaffordable bonds in one of twelve regional jurisdictions in Cesar’s case. Unfortunately, the other jurisdictions remain unprotected, and we have not seen significant decreases in bond amounts overall..

The likelihood of someone receiving a bond that they can’t afford to pay varies between states, cities, courts, and judges. Since 2018, some immigration judges set bonds that over 70 percent of immigrants did not pay within five days and a third did not pay within 30 days; others set bonds that were paid by immigrants that same day almost every time.

The differences between cities are also striking. Since 2018, in Portland, 72 percent of immigrants given bond did not pay within 5 days. In Detroit, 17 percent failed to pay. (It’s important to note that the individuals entering these courts may differ, and these differences, in addition to arbitrary decision making, may cause the disparities between courts.)

Unpaid Bonds by Court Location

Percentage of cases ending in detention for over 5 days by court city (2018)

Note: Cities with fewer than 60 bond hearings between Jan 2018 and Feb 2019 were eliminated from analysis. Numbers are rounded to the nearest percentage.

Let’s end poverty-based detention

There are compelling arguments that we should not rely on money bond at all to guarantee a person shows up in court. Doing so discriminates against the poor without making our communities any safer. But where we use bond, there must be basic protections to ensure that people aren’t locked up simply because they cannot afford to go free. Instead, these systems could offer alternative conditions of supervision such as check-ins or travel restrictions. These, and even less intrusive measures, like sending text message reminders, are typically enough to ensure that the person shows up to court.But And if we where wedouse bond, there must be basic protections to ensure that people aren’t locked up simply because they cannot afford to go free.

At the very least, judges who set bond amounts should be required to consider the person’s finances before doing so. That’s basic common sense, and our litigation has brought this much needed change to one region of the country. As we continue to expand this work, Congress should also act. A bill introduced in the House and Senate — the Dignity for Detained Immigrants Act — would impose critical reforms to prevent the imprisonment of immigrants based on poverty. Under the Act, all immigrants detained by ICE will receive a prompt bond hearing before an immigration judge. The judge will order the person’s release unless the government establishes that alternatives to detention will not ensure his or her appearance in court or that the person poses a threat to the community. Moreover, consistent with the federal bail laws, the Act requires the judge to impose the least restrictive conditions of release—including release on recognizance, bond, or community supervision. And if the judge decides to set a bond, he or she must consider the person’s ability to pay the bond without imposing a financial hardship.

The bottom line is that no one should be imprisoned because they cannot afford the price tag of being free. As the Trump administration continues to ramp up the immigration detention system, it’s crucial that we reform the bond system.

For further detail on analysis, please read ACLU Analytics team’s methodology report here.

Related Stories

The Real Border Crisis | American Civil Liberties Union