Brown at 60: The Promise of School Integration and the Rise of Re-segregation and the School-to-Prison Pipeline

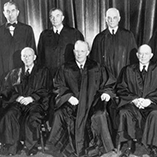

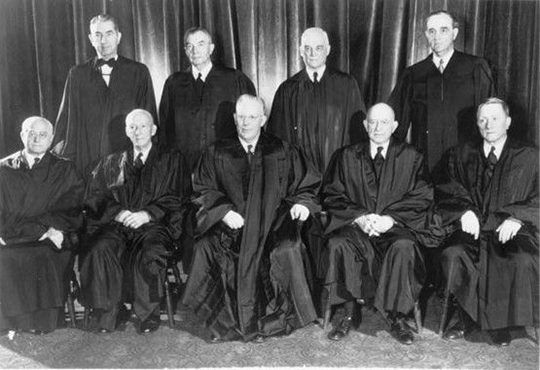

"We conclude that in the field of public education,

the doctrine of separate but equal has no place."

Chief Justice Earl Warren

writing for the Supreme Court

May 17, 1954

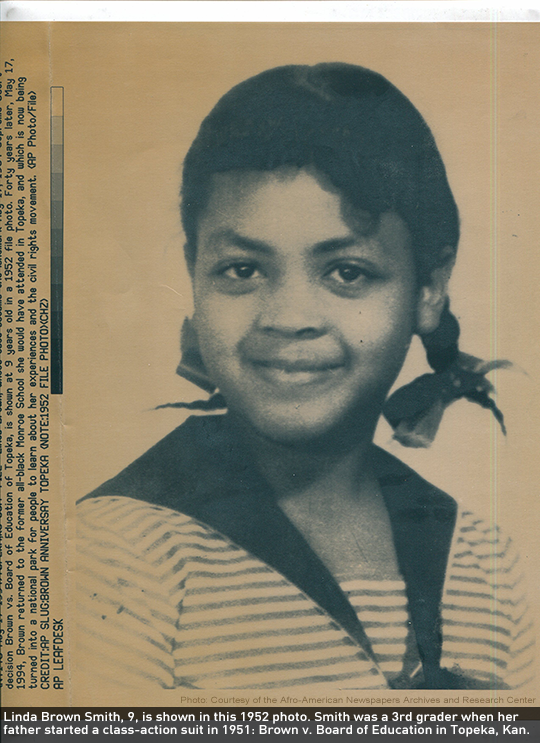

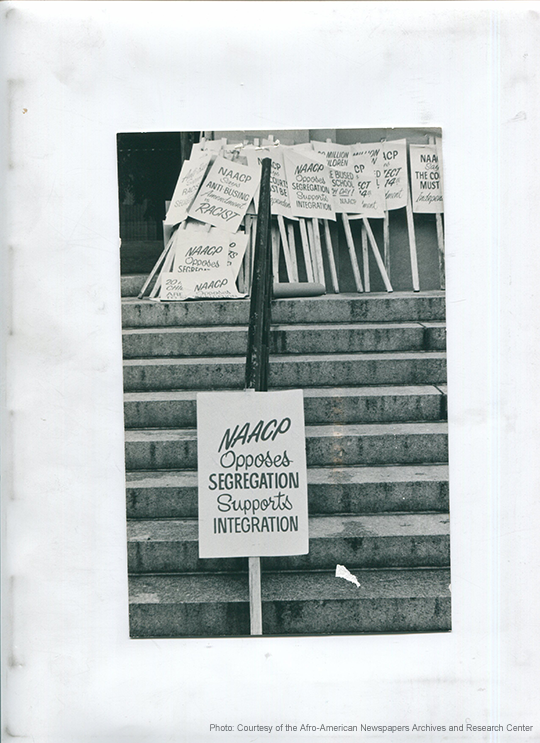

The landmark Brown v. Board of Education ruling struck down the separate, but equal doctrine and declared school segregation unconstitutional. The ACLU submitted an amicus brief supporting the NAACP’s argument in Brown and continued to support plaintiffs in the decades-long battle for equal educational access and opportunity.

1955 - Brown II

In the follow-up to Brown v. Board of Education the Supreme Court decreed that the dismantling of separate school systems for Blacks and whites could proceed with “all deliberate speed,” sparking massive resistance to desegregation throughout the country—and especially in the South.

1956 - Bush v. Orleans and Ruby Bridges

The case of the 6-year-old girl is etched into the collective memory of an era, inspiring the iconic Norman Rockwell painting of hope and defiance.

U.S. District Court Judge J. Skelly Wright ordered New Orleans public schools to desegregate on a grade-per-year basis, beginning with the first grade. White parents withdrew their children from school, forcing Ruby, escorted by federal marshals, to complete the first grade alone.

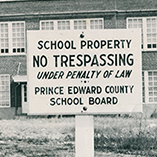

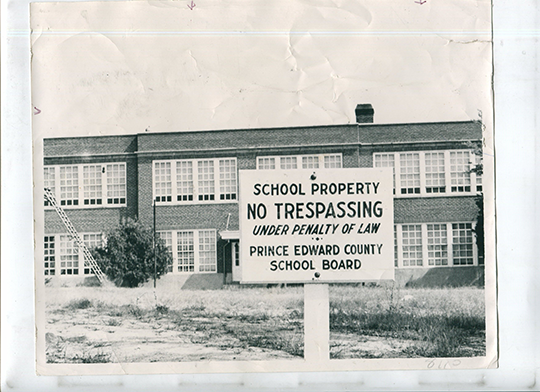

1956 - Massive Resistance

Devised by Virginia’s Senator Harry F. Byrd Sr., massive resistance was an all-out effort to preserve racial segregation. Actions included closing public schools, ending mandatory school attendance, redrawing district lines, providing vouchers to white parents for private schools, and refusing to fund integrated schools. Prince Edward County closed all its schools and created white private academies rather than integrate, leaving the county’s Black students with no access to public education for four years.

1959 - Aaron v. Cooper and the Little Rock Nine

A group of nine Black students endured violence, verbal abuse and social isolation after integrating Central High in Little Rock, Ark. Governor Orval Faubus called the National Guard to surround Central High, declaring that “blood would run in the streets” if Black students attempted to enter. Federal troops finally escorted the Nine into Central High by order of President Eisenhower.

1964 - Civil Rights Act

Shepherded by President Lyndon Johnson, Congress outlawed racial segregation in public accommodations and transportation. The Act’s Title VI created a powerful enforcement tool by banning the use of federal funds for local or state governments that discriminate.

1970 - Tallulah Morgan v. James Hennigan

Boston, once a center of the abolition movement, would become a cauldron of white resistance to integration. Black parents successfully argued that the Boston School Committee violated the 14th Amendment by its deliberate policy of racial segregation. Judge W. Arthur Garrity Jr. ruled that the School Committee had knowingly carried out a systematic program of segregation.

By mid-decade, anti-busing protests turned violent. The case continued through 1994, when a final judgment permanently prohibited the School Committee from practicing racial discrimination.

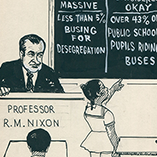

1971 - Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education

The Supreme Court unanimously upheld busing programs to speed racial integration of public schools. In Charlotte, N.C., nearly 95 percent of Black children still attended segregated schools almost 20 years after Brown, with busing used to maintain segregation. The NAACP sued the Charlotte-Mecklenburg school district on behalf of Vera and Darius Swann to allow their son to attend one of Charlotte’s few integrated schools, and the one closest to their home.

1974 - Milliken v. Bradley

Detroit’s white flight and rigid housing segregation ensured that public schools remained racially segregated. Black parents and the Detroit Branch NAACP sued the Michigan State Board of Education, charging the schools with deliberate racial discrimination. The Supreme Court rejected the argument. In a stinging dissent, Justice Thurgood Marshall, lawyer for the Brown plaintiffs in 1954, accused the court of taking a giant step backward:

We deal here with the right of all of our children, whatever their race, to an equal start in life and to an equal opportunity to reach their full potential as citizens. Those children who have been denied that right in the past deserve better than to see fences thrown up to deny them that right in the future. Our Nation, I fear, will be ill-served by the Court’s refusal to remedy separate and unequal education, for unless our children begin to learn together, there is little hope that our people will ever learn to live together.

1979 - Brown Legacy Cases

When open school enrollment policies in Topeka, Kan., threatened to derail integration, the ACLU filed suit. Working with attorneys Richard Jones, Joseph Johnson and Charles Scott Jr. (son of one of the attorneys in the original Brown case), the plaintiffs prevailed by the late 1980s. Topeka Public Schools were found to be out of compliance, and a court-ordered plan to remove the last vestiges of school segregation was issued on July 25, 1994.

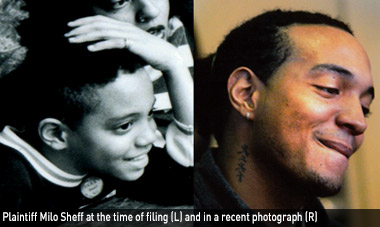

1989 - Sheff v. O'Neill

The struggle to end segregation in Hartford, Conn., schools lasted nearly two decades. Today, 42 percent of Hartford children attend integrated schools; the ACLU is currently negotiating a plan to end racial isolation for the remaining 59 percent.

1990s - Zero Tolerance

School districts begin enacting “zero tolerance” policies, an array of harsh discipline policies that often treated minor infractions with excessive punishment. Although policies vary by district, 79 percent of all school districts adopted some form of zero tolerance by 1997.

1994 - Bradford v. Maryland

Charging that Maryland provided an inadequate education, the ACLU fought to win equal educational resources for Baltimore schoolchildren. Bradford established that the education Baltimore students were receiving was not “constitutionally adequate.” The 1997 settlement mandated increased funding for Baltimore City schools, enshrined into law in SB 795.

2000 - Williams v. California

California agreed to settle a landmark civil rights case brought by the ACLU to ensure quality learning conditions for millions of low-income students of color. Williams created new standards for measuring the basic conditions students need in order to learn, such as textbooks, well-trained teachers, and clean and safe school facilities.

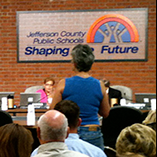

2006 - PICS v. Seattle and McFarland v. Jefferson County Public Schools

The ACLU submitted an amicus brief before the Supreme Court. The Court ultimately rejected the constitutionality of school district plans in Seattle and Louisville that, in an effort to address racial segregation in K-12 schools, used race as a factor in student assignment.

2004 - McFarland v. Jefferson County Public Schools

From 1973 to 2000, Jefferson County operated under federal court supervision under which it was compelled to take steps to desegregate schools which had previously been segregated unconstitutionally on the basis of race. During the period of court supervision, the school district used various methods to eliminate unconstitutional segregation. Once court supervision ended, the Jefferson County School District made efforts to maintain desegregated schools, arguing that maintaining racially integrated learning environments benefited all students educationally.

2007 - Global Debate

The ACLU elevated the school-to-prison pipeline into the human rights arena with its shadow report to the United Nations. Turning a Blind Eye to INJustice documented state-by-state data that ran counter to the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination.

2010 - Student Safety Act

The New York Civil Liberties Union led a three-year advocacy campaign to create the Student Safety Act. The Act requires quarterly reporting by the Department of Education and the New York Police Department on school safety issues, including arrest, expulsion and suspension of students.

November 2013 - Broward County Agreement

The nation’s sixth-largest school district signed an agreement with the NAACP that offers alternatives to arrests and overly harsh discipline rules.

January 2014 - Department of Justice and Department of Education School Discipline Guidelines

The jointly issued school discipline guidelines particularly take aim at discriminatory and excessive practices against students of color and students with disabilities. During a news conference late last year, Attorney General Eric Holder declared, “School discipline should end in a principal’s office, not a police station.”