Raul and his four children. He and his 10-year-old son were separated by immigration officials in Arizona in March 2018 (Guillermo Arias/ACLU).

Separated from their Children by U.S. Immigration, Jubilation as These Parents Win Entry in Mexicali

Meet some of the 29 separated parents who crossed into U.S. territory to make asylum claims at a border checkpoint on Saturday.

By Ashoka Mukpo

March 8, 2019

When Nery crossed through the heavy iron gate into the United States from a border checkpoint in Mexicali on Saturday, it was a major step in a harrowing journey that began nearly a year ago and spanned three countries. Last May, Nery and his teenage son fled Guatemala after being threatened and attacked over their support for a local politician. They traveled north through Mexico across the U.S. border, where the two presented themselves to immigration officials hoping to seek asylum. What they didn’t know was they’d arrived during the height of the Trump administration’s “zero tolerance” policy, and after three days, the two were separated in an immigration holding center. A month later, Nery was deported back to Guatemala without his son, who was placed in a shelter in New York.

Nery and his teenage son fled Guatemala after being threatened over their support for a local politician (Guillermo Arias/ACLU).

At dawn on Saturday, Nery arrived at the checkpoint along with 28 other parents who’d also been separated from their children under “zero tolerance” to ask for asylum under U.S. law. All were members of a group of around 430 people who were separated from their children and then deported to their home countries without those children beginning in late 2017. For weeks, these parents and their families — 54 people in total — had been waiting in a hotel in Tijuana under the watchful eye of Al Otro Lado, a legal services organization based in Los Angeles. All had harrowing tales of violence and persecution they had suffered in their home countries as well as abuse at the hands of immigration officials at the U.S. border.

“I want my son,” said Lorenca, an indigenous woman who’d escaped persecution in Guatemala. “I just want to be reunited with my son.” (To protect their privacy, the parents are identified here only by their first names or, in some cases, pseudonyms).

There was “Hector,” who’d fled Honduras after being savagely beaten and tortured for political reasons, narrowly escaping his attackers by jumping into a river. Two months after being separated from his 16-year-old son by immigration officers in January 2018, he went on hunger strike when ICE agents refused to let the two speak over the phone.

Hector fled Honduras after he was attacked and had his house burned down for political reasons (Guillermo Arias/ACLU).

“Every time he talks to us, he asks about everyone and cries,” Hector said about his son. “He misses us a lot.”

“Lilian” fled violence and threats in El Salvador, bringing her 13-year-old daughter north with her to what she hoped would be safety. After crossing the border, the two were separated on Christmas Day in 2017.

“They took away our kids as if they weren’t ours,” she said. “Shackled our hands, feet, and waist as if we were criminals and snatched away our kids without mercy or compassion.”

During her initial interview with immigration officials, she says one laughed, turned to the others, and said, “Fuck these Salvadorans.”

Lilian and her 13-year-old daughter were separated by immigration officials on Christmas Day in 2017 (Guillermo Arias/ACLU).

Elmer left Honduras after his father was murdered, surviving an attempt on his life and threats to his teenage daughter. In mid-June of 2018, he was deported back to Honduras without her after being picked up by Border Patrol officers near Brownsville, Texas. Almost immediately after his deportation he fled north to Guatemala, fearing that his life would be in jeopardy if he remained in Honduras.

Raul had his wife and four children with him. He’d escaped threats made to him and his family in Guatemala, leaving for Mexico in March 2018 and crossing the U.S. border in Arizona with his 10-year-old son. The two were arrested and days later separated in a hielera — a border detention facility commonly called “the freezer.” Raul was sent back to Guatemala in early April after being misled into signing a deportation agreement that ended his asylum claim. For months his son was transferred between different facilities, eventually landing with a foster family who repeatedly asked him whether he wanted them to adopt him.

The boy told Raul that he wanted to come home, so despite his fears, he elected to have him returned to the family that August. On his phone, Raul displayed photos of his son holding up medication that he’d begun taking in order to cope with the nightmares he’d been having since his detention. Horrified at her son’s ordeal, Raul’s wife had nearly miscarried their baby daughter, who they’d named “Genesis” to symbolize a new beginning for their family. Although reunited with their son, Raul still hoped to follow through with the asylum claim he’d been pressured into dropping last year.

Raul's son began taking medication to cope with the nightmares he’d been having since his detention (Guillermo Arias/ACLU).

There was also Javier, who’d been held at gunpoint in his home in Honduras by four armed men. In May 2018 he was separated from his 14-year-old son and was deported three weeks later after signing papers he said he couldn’t read.

And Jose, who’d been separated from his 15-year-old daughter that same month after fleeing Honduras. He spoke about his hope to be reunited with his daughter away from the peril they’d left behind. “I want to give her a hug and tell her now I’m here,” he said. “We are family, and we are safe from danger.”

A Devil's Bargain

After a wave of public outrage over the Trump administration’s family separation policy and a court order resulting from an ACLU lawsuit, the parents at the hotel had been given the choice to have their children join them. But for many, it was a devil’s bargain. They’d originally fled with their children because of threats of violence and persecution, and they feared that if their children were sent back that they could be hurt or worse. So they made an excruciating decision to allow those children to remain in the U.S. and pursue their own asylum claims, even if it meant that there would be no way to predict when, if ever, they’d see one another again.

Girl walking around the hotel (Guillermo Arias/ACLU).

“Parents should never be forced to choose between reuniting with their children and keeping them safe, yet that is the agonizing decision forced upon these parents,” said Lee Gelernt, the lead ACLU lawyer in the Ms. L. v ICE family separation lawsuit.

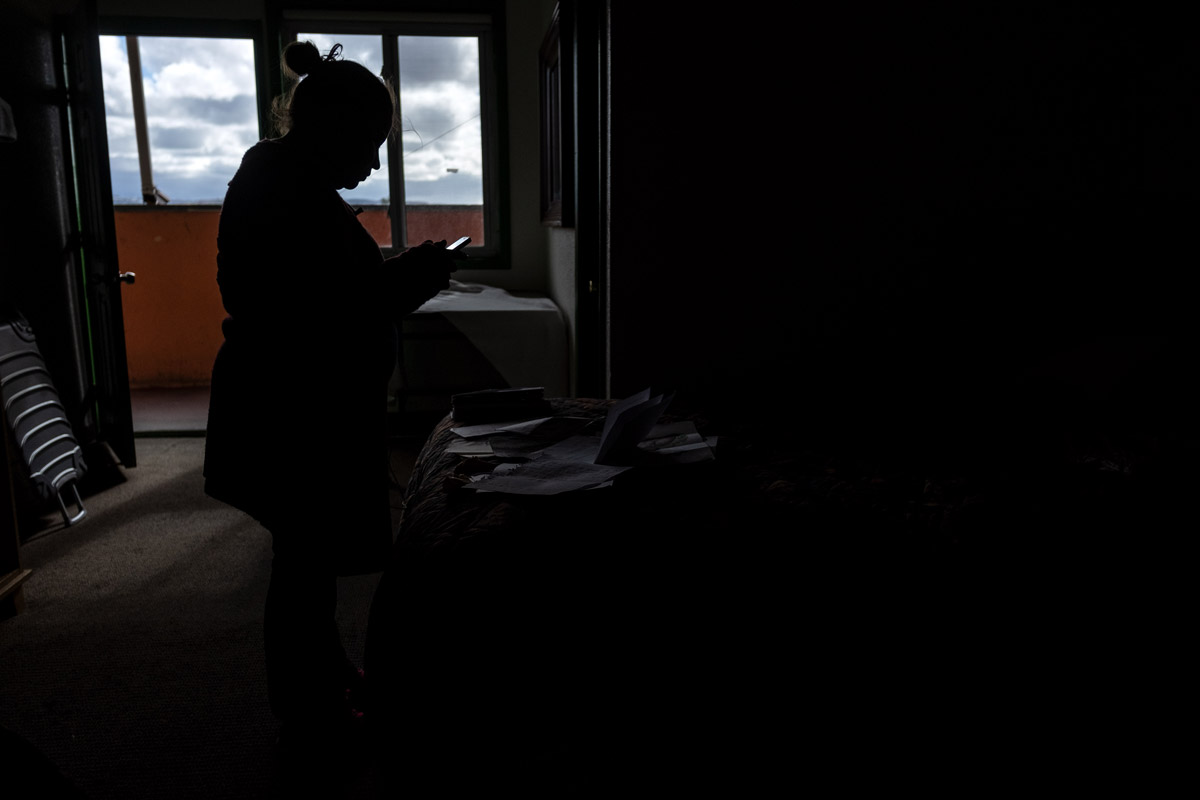

“We have children on the other side who aren’t even with a family member, but with strangers,” said “Hector,” in his dimly lit room at the hotel, which often serves as a landing spot for people deported from the U.S. “As a parent, I don’t even know what kind of family has my son right now.”

Lawyers from Al Otro Lado had brought the parents to the hotel in anticipation of having the group present themselves en masse to cross the border for asylum proceedings. In recent months, this has become harder, with the Trump administration beginning to roll out a policy that forces asylum seekers to wait in potentially dangerous situations in Mexico rather than inside the United States while their claim is processed. (The ACLU filed suit on Feb. 14 challenging the policy. Al Otro Lado is one of the plaintiffs.)

The parents’ presence in Mexico was the culmination of a months-long process by Al Otro Lado and its partners. After a judge ordered the Trump administration to end its family separation policy in late June of last year, the ACLU and a steering committee comprised of the law firm Paul Weiss along with three nonprofit organizations — Justice in Motion, Women’s Refugee Commission, and KIND — undertook a complicated and difficult effort, with help from Al Otro Lado, to find the parents who’d already been deported. Among the hardest cases were those who’d initially traveled to the U.S. with their children to seek asylum and had since gone into hiding.

Hotel (Guillermo Arias/ACLU)

“In Honduras, the security situation was really serious,” said Erika Pinheiro, Al Otro Lado’s legal and policy director. “Many of the parents we were visiting were moving from place to place to avoid persecutors or really living in dangerous situations.”

Interviews with the parents revealed that many had been deported back to perilous circumstances, and they had only dropped their initial asylum claims under duress. Some said they’d been pushed to sign forms they couldn’t read and which they were told would enable them to see their children again. After the forms turned out to be deportation agreements, they were sent home without their children with no clear plan for reunification.

“See You on the Other Side”

Twenty-nine agreed to return with the help of Al Otro Lado, obtaining transit visas at the Guatemala-Mexico border during a tense 18-hour negotiation and traveling to Northern Mexico in early February.

As days dragged into weeks, the families slowly got to know one another. Al Otro Lado staff and hotel employees shuttled the parents and young children to nearby dentists and doctors, while volunteer immigration lawyers dropped in to explain the byzantine U.S. asylum system. The parents talked about their children inside the United States in quiet, pained tones.

Two asylum seekers talking at dusk (Guillermo Arias/ACLU).

“I wouldn’t care if I didn’t make it inside,” said “Lilian.” “If I could just look at her at the border and touch her hands I’d be happy.”

After two long weeks of waiting, Al Otro Lado staff set a date — March 2 — for the group to present themselves to border officials at Mexicali for their asylum claims. As that day crept closer, nerves began to fray as the prospect of an arduous journey through the U.S. immigration system loomed ahead.

“We might get them out of CBP custody at the port of entry,” Pinhiero said, “but they have to be ready to be detained for their entire proceedings.” In some cases, asylum proceedings can last for several years.

Nery shrugged off concerns about the long process ahead. “If you have a child there, and you know he needs you, you’d do the impossible, right?” he said. “They say that a parent will do anything for a child, and that’s the perfect word. Anything.”

Lorenca, an indigenous woman from Guatemala, was separated from her son near El Paso, Texas, in July 2018 (Guillermo Arias/ACLU).

On Friday, March 1, the group boarded charter buses and drove across the arid Mexican desert to Mexicali, a hundred miles to the east of Tijuana. But before their attempt at claiming asylum, there was one last order of business: a wedding. Fearing a long separation could be near, Elmer and his fiancée had decided to marry. To the cheers of the gathered families, the two stood in a hotel lobby and were married by Alexia Salvatierra, a minister who would also accompany the families to the border checkpoint along with other church leaders the next day.

Early Saturday morning, the parents gathered their belongings and quietly set off on the short walk toward the nearby checkpoint. Some clutched the hands of their young children, rolling their suitcases behind them. But when Pinhiero approached Customs and Border Protection officers to explain who the families were and what they were asking, the response was swift: There was no space, and they’d all have to leave.

The parents refused to give up.

As the hours dragged by, they sat on nearby benches, calling and texting updates to their children in the U.S. Some paced under the hot sun, while young children in the group fiddled with coloring books donated by volunteers. CBP officers requested documents and identification proving that the parents had been separated from their children, but they refused to budge on their willingness to admit and process the group.

“Step by step,” Pinhiero assured the group. “They said that they’re going to call their supervisor again.”

Border checkpoint at Mexicali.

By late afternoon, Al Otro Lado staff members began to prepare themselves for the prospect that the group might have to spend the night at the checkpoint. By then, some news organizations had arrived and were reporting about the families’ journey to the checkpoint. Some celebrities began to tweet their support. Ten hours after their arrival, Pinhiero called the families to attention. Gather your belongings and documents, she said, you’re being admitted.

Waves of jubilation swept through the crowd. Some wiped tears from their eyes.

“I’m so happy, it’s a lot of emotion,” said Nery, waiting in line for his turn. “All the sacrifices were worth the effort.”

As the families went through the gate one-by-one, Al Otro Lado staffers hugged them and wished them luck. “I’ll see you on the other side,” one said. By nightfall, all that remained on the benches were a few candy wrappers and stray papers.

“I’m so relieved,” Pinhiero said. “But it’s not over until they’re back with their kids.”