Terrorism and Economic Injustice After Enslavement

White supremacy is not linear; it is structural, circular, and pervasive. So is this article. To historically address the issue of reparations, it is important to excavate the past and understand the many ways that seemingly random events are incredibly interconnected. Ida B. Wells' pamphlet “Southern Horrors: Lynching Law in All Its Phases” presaged the Wilmington Massacre and the Tulsa Annihilation, and because of the ways these events were reported, we are confident that there were events that went unreported that were equally devastating.

Reparations are not just about a "payback" or a "check." They’re about the ways to repair the economic, political, and social devastation that was deliberately imposed on African-American people in the United States because of fear, economic envy, and a defensive imposition of white supremacy. Absent lynching, intimidation, and Jim Crow, African-American communities in the South, where the majority of the Black population lived, may have thrived.

That was not the plan.

The plan was to subjugate a people, to replicate the conditions of enslavement through law and intimidation. And though Black people asked for little from government, the plan was to offer them even less, to force them to pay, through taxation, for the elevation of the whites who blatantly oppressed them. Thus, this essay is both a discussion about the importance of reparations to close the wealth gap and an examination of a period of U.S. history that is infrequently discussed — the history of intimidation and terrorism of Black people after Reconstruction that culminated, not only in lynchings, but also in the economic evisceration of Black communities. The post-traumatic reactions to these extremely violent episodes are justification for reparations.

Reparations, H.R. 40 and the Path Forward

The latest on Reparations, H.R. 40 and the Path Forward

Source: American Civil Liberties Union

Formerly enslaved people made significant political and economic progress after the 1865 passage of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, the one that abolished slavery and involuntary servitude ("except as punishment for a crime," totally defined by white supremacists). Unshackled, African-American people were able to accumulate property, acquire education, and participate in the political process. Fortunes were accumulated; politicians were elected; and the unwritten rules of white supremacy were challenged with Black participation and with Black excellence. These realities collided with the stereotypes that shaped the many ways that white citizens perceived their Black counterparts. Indeed, during that time, even the invocation of the term "counterparts" (implying equality) might be provocation for the confiscation of property, a beating, or a lynching.

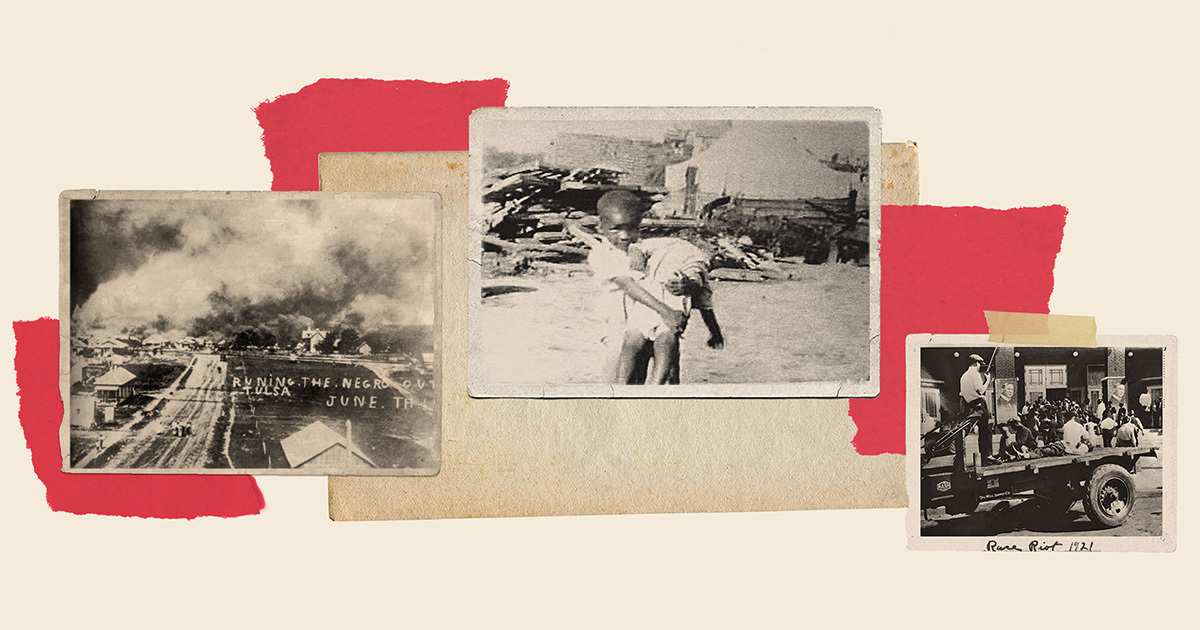

Memphis

Consider Thomas Moss. He was a postal worker, as good a job as a Black man could get in Memphis in 1892. He was a husband, a father, and an entrepreneur. He opened the People's Grocery in the Curve, an area right outside Memphis, Tennessee, competing with another store that previously held a monopoly. Its proprietor, William Barrett was a law-breaking braggart (who had several infractions for selling liquor illegally) whose store was frequented by gamblers. Black women were extremely uncomfortable shopping in his store, and so the People's Grocery was opened and enjoyed patronage from the Black community.

Whites were angry. How dare these Black people open up a store without their permission, taking valuable patronage from them? Whites were indignant, consumed with economic envy that allowed them to detail the possessions that Mr. Moss and his colleagues owned. All it took was an excuse, a lie, for whites to initiate a conflict with Mr. Moss and his colleagues, fabricate a justification for a lynching, kill three Black men, and acquire the People's Grocery assets at a fraction of their worth.

What happened?

Two young boys, one Black, one white, were playing marbles. The white boy was getting beaten, and a fight ensued. He ran into Barrett's store and accused the Black boy of something or other. White men, grown men, came to defend the marble loser. Grown white men went to break up a boy's dispute with guns. Where there are guns, there are shots. Some Black men weren't about to let a young black boy be shot over marbles. They fought back. Later, Barrett returned to the store with armed "deputies," a melee occurred, and shots were fired on both sides. The three Black men who owned or worked in the store were arrested, incarcerated, moved from the jail, and lynched. After the lynchings, the People's Grocery was vandalized by an armed white mob, and Barrett, who orchestrated a lynching to stifle economic competition, acquired the People's Grocery at an eighth of its value!

Ida B. Wells

Wikimedia

The crusading journalist Ida B. Wells was godmother to Thomas Moss' daughter. His lynching was the first she wrote about and investigated. This was a notable lynching because it was not about interracial sexual relations but about economic self-determination. Indeed, her investigations showed that fewer than a third of all lynchings had to do with sex — mostly they had to do with intimidation, to frighten black people from voting or accruing property or asserting themselves in the face of white injustice. And many of the lynchings that had to do with sex were consensual relationships that white women denied, even accusing their lovers of rape when the forbidden relationships were exposed.

Reacting to a spate of lynchings, Wells wrote, "If Southern white men are not careful, they will overreach themselves, and public sentiment will have a reaction; a conclusion will then be reached which will be very damaging to the moral reputation of their women." After writing this editorial, which appeared in the paper she owned, the Memphis Free Speech, Ida B. left Memphis to attend a conference, never to return because her press was destroyed and her life threatened, all because she justifiably questioned the "unassailable" virtue of white women and the abhorrent lynchings of Black men.

The 1892 Memphis lynchings, she wrote, were "our first lesson in white supremacy." The lynchings were a galling attempt to snatch back gains that African Americans had made in that city with the protection of Reconstruction troops. They were a depraved attempt to put Black people "in their place." They had a chilling effect on African-American economic development in that city, but also nationally. Many Black folks simply fled the area, fearing for their safety. Thomas Moss, just before he died, advised Black people to "go west." Wells, herself, ended up based in New York for a time, working for newspaper publisher Thomas Fortune and crossing the country documenting lynchings and lecturing about its horrors.

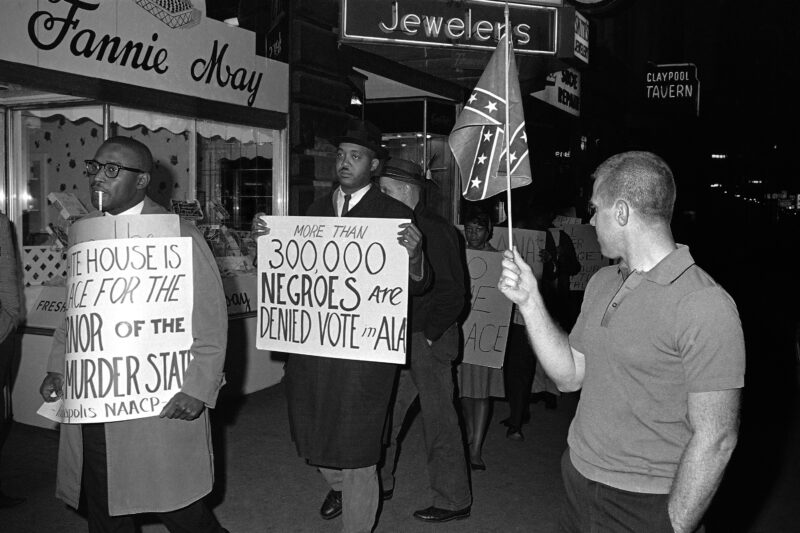

Many will anchor the claim for reparations in the unpaid labor of enslavement, the unpaid work that built the U.S. Capitol and the so-called White House (I prefer to describe it as the House That Enslaved People Built), that undergirded the Southern economy, that was the basis of the U.S. bond market. While all of this is correct, the claim for reparations must also be anchored in the economic, social, and political violence that Black people experienced. Whites who had simmered in white supremacy all their lives used every means they had to reestablish a social order that subjugated Black people in every facet of life. They passed legislation to control everything from the ordinary acts of drinking water and riding on buses to the self-determining actions of buying property and producing newspapers as well as from the citizenship responsibilities of voting to participating in civic life as elected officials.

Whites were absolutely threatened by the gains that Black people made since the end of enslavement, advancements that were not aided by the promised "forty acres and a mule." Indeed, without compensation, and with considerable opposition, the formerly enslaved managed to narrow the wealth gap dramatically. In 1880, just 15 years after enslavement ended, Black folk had $1 for every $36 white people had. In 1890, we had $1 for every $26 that white folks had. In 1900, $1 for every $23 white folks had. In 1910, $1 for every $16 white people had. Look at that progress, we went from 1:36 to 1:16. Today we have $1 for every $14 white folks have, not much better off than we were in 1910.

This is part of the basis of reparations. It is not just that enslavement disadvantaged Black people. It is also that the terrorism inflicted on Black people had consequences in terms of accumulation, participation, and the transmission of generational wealth. After enslavement, without "handouts," and even with the white investment banker-initiated failure of the Freedman's Bank (see “The Color of Money,” by Mehrsa Baradaran), Black folks were attempting to create a space in which we could thrive. But white supremacy prevailed, with a complex and intertwined set of social, political, and economic constraints.

Wilmington

Just six years after Ida B. Wells' friends were lynched in Memphis, Wilmington, North Carolina was incinerated in the event that some call the Wilmington Riot. It is more aptly described as the Wilmington Massacre. As Black and white Republican and independents worked together to gain political leverage, white Democrats — many of whom were Ku Klux Klan members, or part of the Red Shirts (Klan members without hoods) — carefully sowed the seeds of resistance to Black participation. With a carefully executed propaganda campaign, they railed against the "Negrofication" of Wilmington. Local newspapers ran cartoons that depicted inflammatory caricatures of Black savages, rapists, and more.

Meanwhile, Black people in Wilmington had made economic gains; there was a thriving middle class. Black folk outnumbered whites by about 30%, and Black and white men worked on the docks together, earning equal wages. Many whites thought Blacks had a "favored position," although there is no evidence of that. The film, “Wilmington on Fire,” aptly depicts the tensions of the times, tensions so stark that more than 200 white men were deputized as magistrates in a town of fewer than 20,000 people to enforce "law and order," or simply to terrorize Black people. They had police powers, and many of them were part of the White Government Union, a white supremacist group created by the North Carolina Democratic Party.

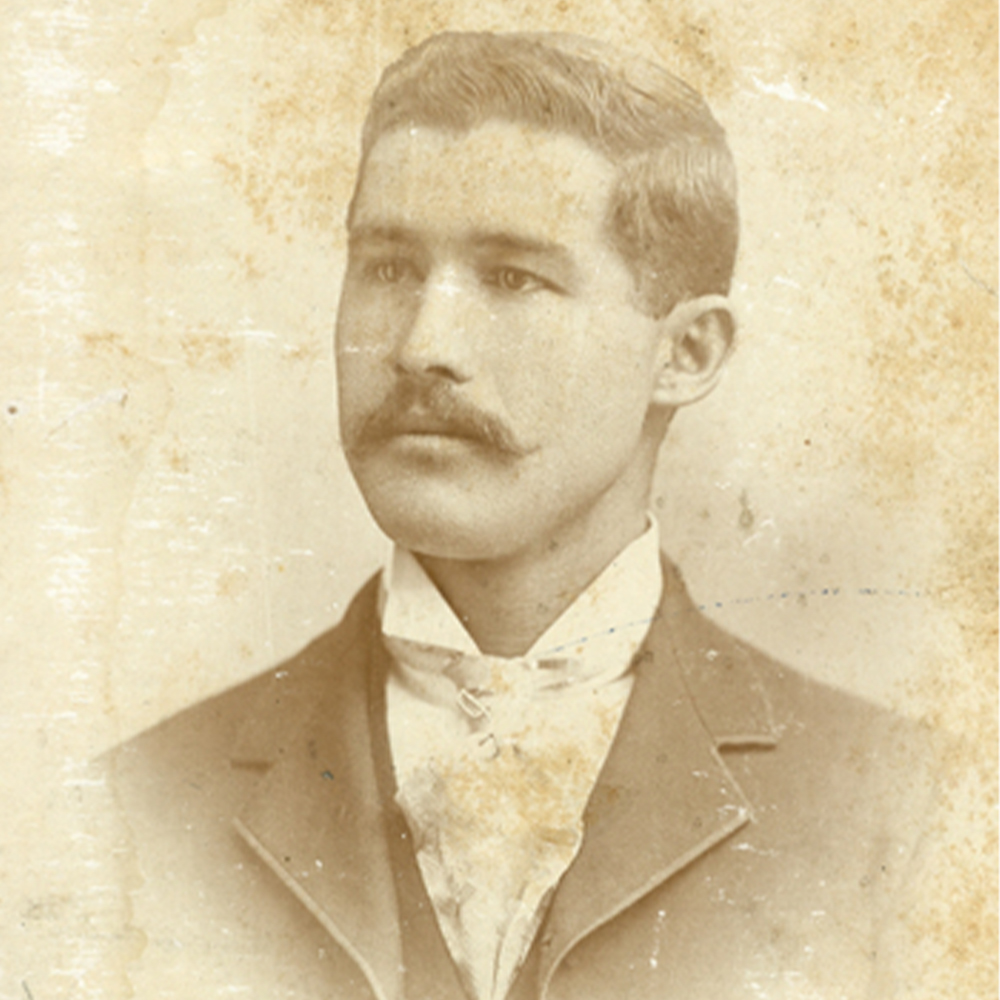

Alexander Manly

Wikimedia

Alexander Manly and his brother, Frank, owned the first Black daily newspaper in the United States, the Daily Record. The paper was widely read, especially in eastern North Carolina. It was a popular and profitable venture that even attracted some white advertisers. But Alex Manly felt compelled to reply when Rebecca Latimer Felton advocated lynching in a public speech. Felton, the Georgia white supremacist and "women's rights advocate," suggested that it would be acceptable to lynch a thousand Black men a day to stop supposed attacks on white women's virtue.

Manly's strong response is reminiscent of the 1892 editorial that Wells wrote, which raised questions about the morality and veracity of white women.

His editorial read, in part:

"We suggest that the whites guard their women more closely, thus giving no opportunity for the human fiend, be he white or black. Our experience among poor white people in the country teaches us that the women of that race are not any more particular in the matter of clandestine meetings with colored men than are the white men with colored women. Meetings of these kinds go on for some time until the woman's infatuation or the man's boldness brig attention them and the man is lynched for rape. Every Negro lynched is called a "big, burly black brute" when in fact many of those were sufficiently attractive for white girls of culture and refinement to fall in love with them as is well known to all."

For whites, Manly's editorial crossed many lines. He called out the white men who had affairs with Black women, a reminder that the consistent rape of Black women was a feature of enslavement. He highlighted interracial relationships in a way that indicated that white women were willing participants in these relationships. The Manly editorial was widely reprinted in the white press to inflame sentiments against Black people. Indeed, Manly and Wilmington became symbols of what happened when Black people had too much power.

When a fusion coalition that included Blacks and Republicans won the 1898 election in Wilmington, white Democrats staged the only coup d 'état that ever took place (so far) in the United States. Armed Red Shirts overturned the city government. On the eve of the election, prominent Black people were arrested and held in jail. The next day they were given one-way tickets out of town, forced to abandon their property and livelihood.

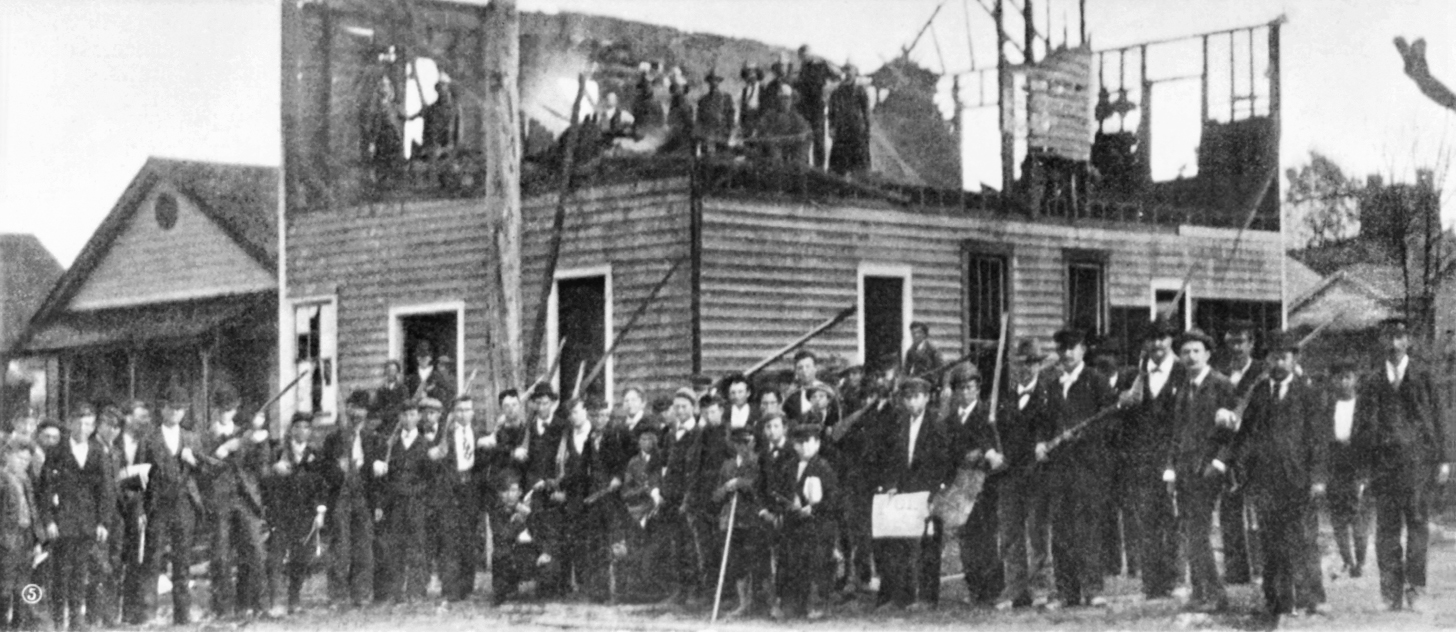

White mob near the ruins of The Daily Record in Wilmington

Wikimedia

The Manly brothers had experienced death threats since the publication of Alex Manly's editorial. On Nov. 10, their press was destroyed, and they barely escaped with their lives. More than 2,100 African Americans permanently moved out of Wilmington, turning it into a majority white city. Estimates of the number of Black people massacred range from 60 to more than 100, and rumors of mass graves suggest that there may have been even more than 100. Whites confiscated the property of the Blacks who left using various "legal" ruses, including the use of the many magistrates who could — based on any pretext — order people to sign their property over to whites.

The Wilmington Massacre, like the Memphis lynchings, had a chilling effect on economic development. According to the economist William Darity, there were 216 Black-owned businesses in Wilmington in 1897. The number fell by more than a quarter to 162 firms in 1900, a startling drop in such a short time. Simultaneously, the number of white-owned businesses grew. Alex Manly never recovered from the Wilmington Massacre. He went from being a newspaper owner and editor to working as a painter to support his family. However, he remained politically active for the rest of his life.

Dr. Lewin Manly, an Atlanta-based dentist, is the grandson of Alex Manly. Featured in the film “Wilmington on Fire,” he speaks of all that his family lost because of the Wilmington Massacre and favors reparations, although he is uncertain of the form they should take. Indeed, the Wilmington Massacre makes a case for both specific and general reparations. Some individuals can trace their losses to economic terrorism, and some communities can also show how they were impacted by the economic manifestation of white supremacy. Further, the shattering of dreams, the restrictions on possibility and potential, the abject daily constraints imposed on a people are justifications for reparations that provide community repair.

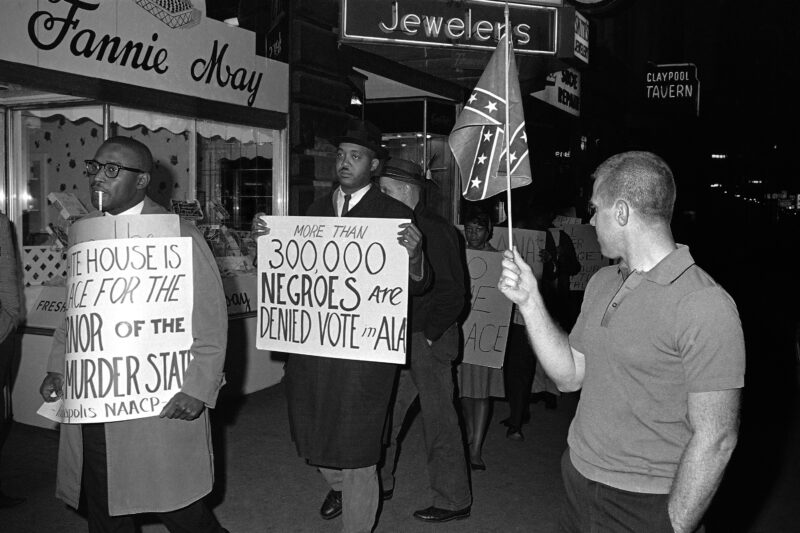

Tulsa

The Greenwood section of Tulsa, Oklahoma, was called "Black Wall Street." There was visible economic prosperity in that community. African Americans owned hotels, a movie theatre, and upscale homes. There was enough wealth in the community that African Americans had built a library and a hospital and, in early 1921, had opened a new church.

African Americans and whites lived largely separately, but there was tension because whites were threatened and envious of the wealth that African Americans enjoyed. There was, however, an income distribution in the African American community. Not all Blacks were wealthy. The Black wealthy were visibly so, to the point that one newspaper wrote that "N---- s in Tulsa have too much money."

Tulsa was also the Wild West. There was an active Klan in Tulsa and a culture of frontier justice. A year before the events that led to the destruction of Black Wall Street, Roy Belton, a white man, was lynched after he robbed and killed a white taxi driver. The owner of one of the Tulsa Black newspapers opined, "If a white could be lynched, what was to stop a mob from lynching a black."

On May 31, 1921, Dick Rowland, a 19-year-old Black man, accidentally jostled Sarah Page, a 17-year-old white elevator operator, when the elevator stopped abruptly. She screamed, and the white man who saw her scream reported that Sarah had been raped. She steadfastly refused to say she was raped or press any charges, but the rumor of rape was enough to incite white people to destroy a thriving Black community and to massacre hundreds of Black people.

Economic envy was the foundation of the Tulsa Annihilation, according to Dr. Olivia Hooker who was, until her death in November 2018, the sole living survivor of that massacre. In a 2015 interview, days before her 100th birthday, Dr. Hooker told me, "We did not have to go downtown" because the community offered everything anyone needed, except a bank. Her father, Samuel Hooker, owned a department store and was a pillar in a community that included pharmacists, doctors, and teachers. One of the many lawyers in Greenwood was John Hope Franklin, Sr., the father of the esteemed historian who carried the same name.

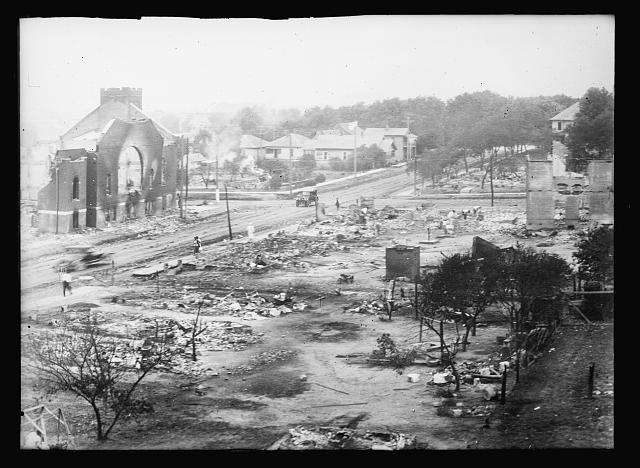

Burned buildings in the aftermath of the Tulsa Massacre

Library of Congress

Whites in Tulsa had been stockpiling weapons to attack the Black community even before the incident. Hooker recalls that one newspaper had the headline, "Negro To Be Lynched Tonight." The lynching never happened because African-American World War I veterans went to the jail to guard Rowland, bringing their weapons to ensure that the young man would not be hurt. The fact that Black men were willing to defend one of their own, along with the rumor of a rape, incited White Tulsans to destroy over a thousand Black-owned homes and businesses and to cause the deaths of between 300 and 1,000 people. The damages were estimated to be at least $3 million in 1921 dollars.

Armed white people went into the Greenwood section of Tulsa on the evening of May 31. They ransacked homes and shot people. Their economic envy was on full display as they took things they felt Black people had no right to own. Dr. Hooker remembers hiding under a table as people came into her family home and broke her mother's "Caruso records," stepped on her doll, and vandalized her home. Black people were held in concentration camp-like settings — some for as long as two weeks after the massacre or until a white person was willing to vouch for them. Some middle-class Black women were released only if they were willing to work in a subservient capacity for white people. They were being "put in their place" because they had too much.

At 100 years old, Dr. Olivia Hooker was still talking about Greenwood and Black Wall Street, always insisting that the handful of survivors and their descendants deserve justice, restitution, and reparations. The Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot recommended the same thing after spending several years investigating the massacre. The commission submitted a report to the Oklahoma Legislature in 2001, but its recommendations have been ignored.

There are indications that Tulsa was bombed by United States Army planes. No one was ever indicted, tried, or convicted for the carnage in Tulsa. The destruction of a thriving Black community was a blow to Black Tulsans and to African-American people nationwide. The state of Oklahoma owes reparations, but so does the United States that sent troops and bombed Black Tulsa to reinforce white supremacy.

What We Must Do

Lynchings and massacres in Memphis, Wilmington, and Tulsa were just a few of the violent and suppressive incidents that took place in the “land of the free.” In some instances, after a lynching, Black people were simply banished from their homes, and their property confiscated. Some of these instances are documented and many are not.

After the passage of the 13th Amendment, African-American people did all they could to thrive, including opening banks, starting businesses, and engaging in civic life. White supremacists were not prepared for Black progress, and the federal government, after Reconstruction, was not inclined to protect Black rights. Thus there were thousands of lynchings, used to intimidate and respond to Black economic progress.

Racist legislators were also more than willing to use public policy as a tool for subjugation. The Homestead Act of 1862 distributed hundreds of millions of acres to white immigrants, but formerly enslaved people were unable to get a fraction of that land. Depression-era economic considerations often excluded African-American people. Post-World War II legislation that provided education and housing possibilities for whites all too often excluded Black people, with federally sponsored redlining encouraging segregated housing.

Norwegian immigrants in front of a sod house

Wikimedia

What must we do?

Kent Chatfield, the researcher who helped document the atrocities of 1898 in Wilmington and who was featured in “Wilmington on Fire,” said, "You can't right a wrong through the passage of time." Ignoring a century of post-enslavement economic intimidation will not narrow the wealth gap. Mindful and intentional action is necessary.

The passage of H.R. 40 is a necessary first step.

The legislation, first introduced in 1989 by Rep. John Conyers (D-Mich.) is now being led by Rep. Sheila Jackson-Lee (D-Texas), and companion legislation has been introduced in the Senate. The bill would establish a federal commission to study and develop reparations proposals.

As Congress takes up H.R. 40, some aspects of restorative justice can take place immediately. Restorative funding of historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) so that these very critical schools can truly thrive could happen with more resources provided by the Department of Education and state departments of education. In terms of land, housing, and gentrification, vacant properties in cities could be granted to African-American organizations for community development.

Corporations and universities that have participated in the gains from enslavement and economic terrorism can begin the process of restorative justice, even absent legislation. The students of Georgetown University, for example, have been courageous in acknowledging the ways they benefited from the sale of enslaved people and passed a referendum to support compensation to the descendants of those who were once owned and sold by the Jesuit university.

The National African American Reparations Commission has developed a 10-point reparations platform that calls for a formal apology, land, education, health care, the protection of sacred sites, criminal justice reform, and more. Its implementation places African-American people on a more level playing field economically, educationally, and politically.

In the very short run, lawmakers must examine any legislation through an equity impact assessment lens. If legislation has a deleterious effect on the African-American community, it must be altered. We have had 400 years of adverse impact, from enslavement to economic intimidation to Jim Crow to its ugly aftermath. It takes more than the passage of time to right the wrongs of white supremacy. It takes mindful and deliberate action. We as a nation need to embrace reparations now.

Reparations for Slavery Now

It's a necessary step for America to advance racial justice. And momentum is building.

Source: American Civil Liberties Union