This was originally posted on The Huffington Post.

Click here to read an original op-ed from the TED speaker who inspired this post and watch the TEDTalk below.

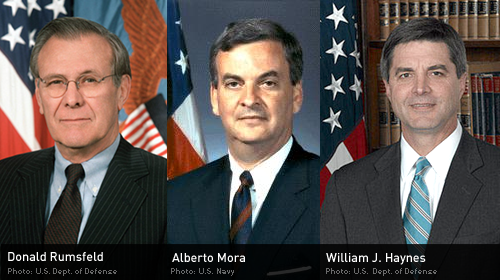

Trained in the Geneva Conventions and the Uniform Code of Military Justice, the military interrogators and guards who tortured and dehumanized prisoners in U.S. custody after 9/11 were hardly without ethical bearings. But as Alberto Mora, former chief counsel of the Navy, predicted when he discovered Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld had authorized previously banned interrogation techniques,

Once the initial barrier against the use of improper force had been breached, a phenomenon known as "force drift" would almost certainly begin to come into play. This term describes the observed tendency among interrogators who rely on force. If some force is good, these people come to believe, then the application of more force must be better. Thus, the level of force applied against an uncooperative witness tends to escalate such that, if left unchecked, force levels, to include torture, could be reached.

Mora memorialized his concerns in a statement for the Navy's inspector general, and he was right, of course: set aside the Geneva Conventions and the other bulwarks that keep cruelty in check, and soon interrogators are shackling prisoners in excruciating stress positions, confining them in freezing cells, and terrorizing them with dogs. A mountain of once-secret documents shows the "Lucifer effect" at work in detention facilities from CIA black sites and Afghanistan to Iraq and Guantánamo.

Like so many of the documents in the declassified files, though, Mora's Statement for the Record shows that what Zimbardo calls "the heroic imagination" was also very much at work, up and down the chain of command throughout the military and intelligence services. Indeed, as we have written previously, the reason we have such a vivid and damning documentary record is that so many women and men stood up and spoke out against the abuse of prisoners.

Many, like Mora, committed themselves to paper specifically because they wanted to build a historical record of the descent into torture and of their efforts to check the slide. In Mora's case, his account includes a remarkable exchange with Secretary Rumsfeld's Chief Counsel, William "Jim" Haynes, over Rumsfeld's infamous handwritten addition note on his interrogation directive, "I stand for 8-10 hours a day. Why is standing limited to four hours?"

Although, having some sense of the Secretary's verbal style, I was confident the comment was intended to be jocular, defense attorneys for the detainees were sure to interpret it otherwise. Unless withdrawn rapidly, the memo was sure to be discovered and used at trial in the military commissions. The Secretary's signature on the memo ensured that he would be called as a witness. I told Mr. Haynes he could be sure that, at the end of what would be a long interrogation, the defense attorney would then refer the Secretary to the notation and ask whether it was not intended as a coded message, a written nod-and-a-wink to interrogators to the effect that they should not feel bound by the limits set in the memo, but consider themselves authorized to do what was necessary to obtain the necessary information.

Mora's brave dissent derives strength from a clear vision of future consequence: there will be adversarial legal proceedings for detainees; during those proceedings, there will be examinations of the means by which testimony was extracted; during those examinations, Rumsfeld himself will inevitably be called to account for approving those methods. It is clear throughout the documentary record that the heroic imagination of those who dissented was driven in no small part by a vision of how the actions they were being asked to engage in or approve would be viewed in the future.

The 2004 report of the CIA's inspector general -- a crucial document of dissent in itself -- was the result of an investigation the IG launched when CIA agents returning from the field "expressed unsolicited concern about the possibility of recrimination or legal action." As the IG recorded, "One officer expressed concern that one day, an Agency officer will wind up on some 'wanted list' to appear before the World Court for war crimes stemming from activities [redacted]."

In Guantánamo, an alarmed Navy Criminal Investigation Task Force agent sent minutes from a meeting with a CIA attorney on interrogation techniques -- the meeting in which the attorney sardonically advised "if the detainee dies, you're doing it wrong" -- up the chain of command, along with the note, "This looks like the kinds of stuff Congressional hearings are made of." The techniques discussed (and later used) would seem, the agent said, "to stretch beyond the bounds of legal propriety" and would very likely "shock the conscience of any legal body looking at using the results of the interrogations or possibly even the interrogators."

An interrogator in Iraq, on receiving a memo instructing that "The gloves are coming off gentlemen regarding these detainees," fired back a message saying, simply, "As for 'the gloves need to come off,' we need to take a deep breath and remember who we are."

And when military interrogators were unleashed in Guantánamo in 2002, FBI agents opened a file labeled "War Crimes," assuming that eventually a prosecutor would examine the evidence and charge those who had violated the law.

All of these men and women, and the others like them who in many cases risked promotions and even their positions to raise their voices against torture, were looking to the future; they were, in fact, looking to us. It is now the future. But we are not, so far, the people they anticipated. The kind of reckoning they were certain would come has not happened; the kinds of judgments they foresaw have not come to pass. Where they were counting on us to assume the moral burden they were forced to carry, at considerable personal risk and largely in secret, for so long, we have failed them. We have left them to bear the burden of conscience for all of us.

What will this do to the heroic imagination in the future? As appalling as the results of the Stanford experiment were, afterwards there was a reckoning of sorts: we collectively acknowledged the Lucifer effect; we deplored those who succumbed to it and admired those who didn't. But imagine the experiment without that kind of retrospective evaluation -- imagine the results weren't published, say, and that those who resisted evil never had the actions affirmed. Now run the experiment with the same group again. Will we have the same number of ordinary heroes? Or will there now be fewer?

Learn more about torture and other civil liberty issues: Sign up for breaking news alerts, follow us on Twitter, and like us on Facebook.