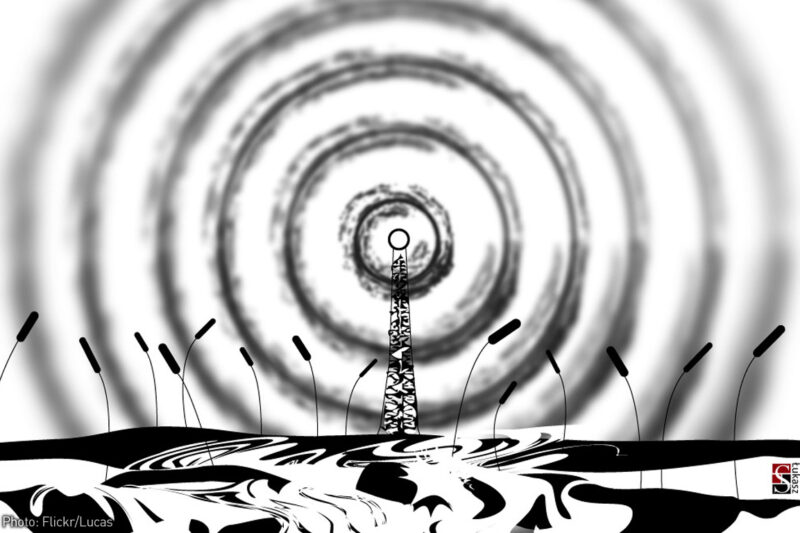

Yesterday, DHS released its new policy on the use of Stingrays—mass surveillance devices used by police to identify and track phones, often without a warrant. The new policy, presented at this Congressional hearing, came only after pressure was created by several high profile media stories, Congressional inquiries, and similar DOJ guidance. (More information about how Stingrays operate—impersonating legitimate cell phone towers and sweeping up location and device information for all phones within range—is here).

First, the bad news.

Stingrays are sort of like a surveillance Atari—they were once cutting-edge, but are light years behind newer technologies. Now there are surveillance devices that allow the police to collect the content of calls and texts and even hack into phones. In other words, the government is only now developing a privacy policy for technology that was used domestically beginning in the mid-nineties and has already spread to roughly half the states. And, the policy doesn’t even touch future surveillance devices that may collect the same information or more.

Second, the other piece of bad news: The policy that has been released is riddled with gaps and loopholes. The DHS policy contains several positive elements, such as a default warrant requirement, limits on the retention of information, and a requirement that judges be informed about how the devices operate in warrant applications. These reforms are certainly an improvement over the status quo. But, they are not adequate. There are four main problems.

- The guidance only applies to cases in which Stingrays are used as part of a criminal investigation. In cases where DHS is patrolling the “border” (defined by the government as a 100 mile zone), conducting certain immigration activities, or monitoring conferences (as local police have done)—no protections apply.

- Even in cases where the policy does apply, there are numerous loopholes that permit police to use the device without a warrant. Requiring a warrant in some cases is certainly better than no warrant requirement. But it’s concerning that the policy contains a warrant exception in broadly defined exigent circumstances, undefined “exceptional” situations, and for national security investigations covered by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act.

- The policy does not apply to state or local officials who receive federal funding to purchase Stingrays. So, for example, police in Wisconsin, Florida, and Maryland who have received money from DOJ and DHS to purchase surveillance technology do not need to abide by any of the new privacy protections. In other words, though the federal government has imposed futile and illegitimate secrecy requirements on states who purchase these devices, they have taken no parallel steps to use their leverage to ensure constitutional use. One might think protecting the Constitution would be a higher priority than trying to hide this technology from the American people.

- The policy completely ignores the rights of individuals to be notified when information from a Stingray is being used against them. We now know that prosecutors have made a concerted attempt to hide the use of Stingrays in cases. DOJ has asked prosecutors to refer to Stingray information as information from a “confidential source” in court filings, or, if necessary, drop cases where defendants raise Stingray challenges to prevent disclosure of information. Instead of remedying these practices, the DHS policy is completely silent on the obligation of the government to information individuals when their information is collected and used. The result: individuals most harmed by the Stingrays may continue to be deprived of the information necessary to challenge their legality.

DOJ and DHS should immediately take steps to remedy the deficiencies in their policies, and require greater transparency.

But even this is, at best, a partial solution. We need to stop chasing surveillance technologies, and instead plan for the future. That would begin with comprehensive legislation and agency policies that protect any collection of location, device, or sensitive information—regardless of the technology used. California has already passed a law that takes this approach. The federal government should follow suit.