As the nation celebrates Black History Month, we continue to work to change how the story unfolds for people who live at the margins of our society — including our children.

As the nation celebrates Black History Month, we continue to work to change how the story unfolds for people who live at the margins of our society — including our children.

For most, childhood is remembered as a time of carefree pleasure. When my nieces and nephews wake up in the morning, they know they will eat breakfast, get hugs from their parents, go on play dates, and attend good, safe schools. But for many children, this is more of a dream than a reality.

In There Are No Children Here, journalist Alex Kotlowitz describes the tense atmosphere inside an inner city public school:

Ms. Barone tired of the large classes, which at one point swelled to as many as thirty-four students — they now numbered around twenty-five-and of the funding cutbacks. And she worried so much about her children, many of whom came in tired or sad or distracted, that she eventually developed an ulcerated colon.

The relentless violence of the neighborhood also wore her down. The parking lot behind the school of the neighborhood also wore her down. The parking lot behind the school had been the site of numerous gang battles. When the powerful sounds of .357 Magnums and sawed-off shotguns echoed off the school walls, the streetwise students slid off their chairs and huddled under their desks. The children had had no "duck and cover" drills, as in the early 1960s, when the prospect of a nuclear war with Cuba and the Soviet Union threatened the nation. This was merely their sensible reaction to the possibility of bullets flying through the window.

A child's life awaits a story, like the blank pages of a novel. It is up to parents, family, and the community to shape the story of who each child will become. Ensuring that they have the opportunity to grow up safe, strong and full of hope for the future is not only in their best interest; it's an investment in ours as well. As Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. said nearly 50 years ago, "We are all caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied into a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one destiny, affects all indirectly."

Jennifer Bellamy serves as a legislative counsel in the ACLU's Washington Legislative Office. In addition to representing the ALCU in coalition work connecting a broad political cross section of policy makers, she is a leader of the National Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Coalition and co-chair for the Criminal Justice Task Force of the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights. She holds a B.A. from the University of Alabama and a J.D. from Samford University, Cumberland School of Law.

As the nation celebrated Black History Month, the ACLU continues to work to change how the story unfolds for people who live at the margins of our society — including our children. The ACLU advocates for the passage the Youth PROMISE Act, which provides communities with the support and resources they need to create opportunities for success, keeps kids out of harm's way, and rehabilitates those who have gotten off track. The YPA not only helps break the cycle of violence, but provides much needed positive alternatives for kids, right in their own neighborhoods. This legislation has a profound impact on the dreams of our children.

If given a chance, young people can emerge from even the harshest experiences to achieve beyond all of our expectations. But it is up to us to give them that chance.

Langston Hughes famously asked: "What happens to a dream deferred?"

The answer is up to us.

This blog post is one of several personal testimonials written by ACLU staff members to commemorate Black History Month.

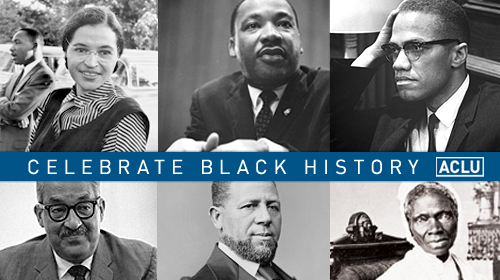

Do you know who’s pictured in our Celebrate Black History logo? Clockwise from top right: Martin Luther King, Jr.; Malcolm X; Sojourner Truth and Rosa Parks.

Learn more about racial justice: Sign up for breaking news alerts, follow us on Twitter, and like us on Facebook.