Five Truths About Black History

Creation stories have emerged from every culture, and in each instance, they have helped to define not only where a people came from — but how we got to where we are as a society. The American creation story is based on freedom, equality, and the pursuit of happiness. That story, like most creation stories, is part true and part myth. Since it’s Black History Month, here are five truths that remain hidden from too many people today.

America was founded on white supremacy

The nation’s founders believed in white supremacy, and they were not ashamed to say so.

The first slaves arrived here in 1619. Between 1619 and 1865, Virginia passed more than 130 slave statutes to regulate the ownership of Black people. A 1662 law made all children of enslaved mothers slaves, regardless of the father’s race or status, so that rape by white slave-masters couldn’t create a free child. A 1667 law codified that slaves who converted to Christianity were still slaves. A 1669 law allowed slaves to be killed for resisting authority.

The wording of the law regarding Christianity is revealing. The slave-masters would claim Christian piety in their acts of enslavement:

WHEREAS some doubts have risen whether children that are slaves by birth, and by the charity and piety of their owners made pertakers of the blessed sacrament of baptisme, should by vertue of their baptisme be made ffree… the conferring of baptisme doth not alter the condition of the person as to his bondage or ffreedome;

Virginia didn’t have a monopoly on horrible slave laws. In 1740, South Carolina passed a comprehensive slave code with 57 provisions “so that the slave may be kept in due subjection and obedience.” Provisions included making it a crime for slaves to grow or possess their own food, gather in groups, or learn to read.

In 1755, Georgia required all plantation owners and their white employees to serve in the state militia, which was responsible for enforcing slavery. Joseph Clay, a Savannah merchant, described the role of slavery in 1784, saying, “The Negro business is a great object with us. It is to the trade of this country as the soul is to the body, and without it no house can gain proper stability.”

Forty of the 56 signers of the Declaration of Independence owned slaves. Under the Constitution, a slave was counted as three-fifths of a free person. Ten of the first 12 presidents owned slaves. This is who we were as the United States became a nation.

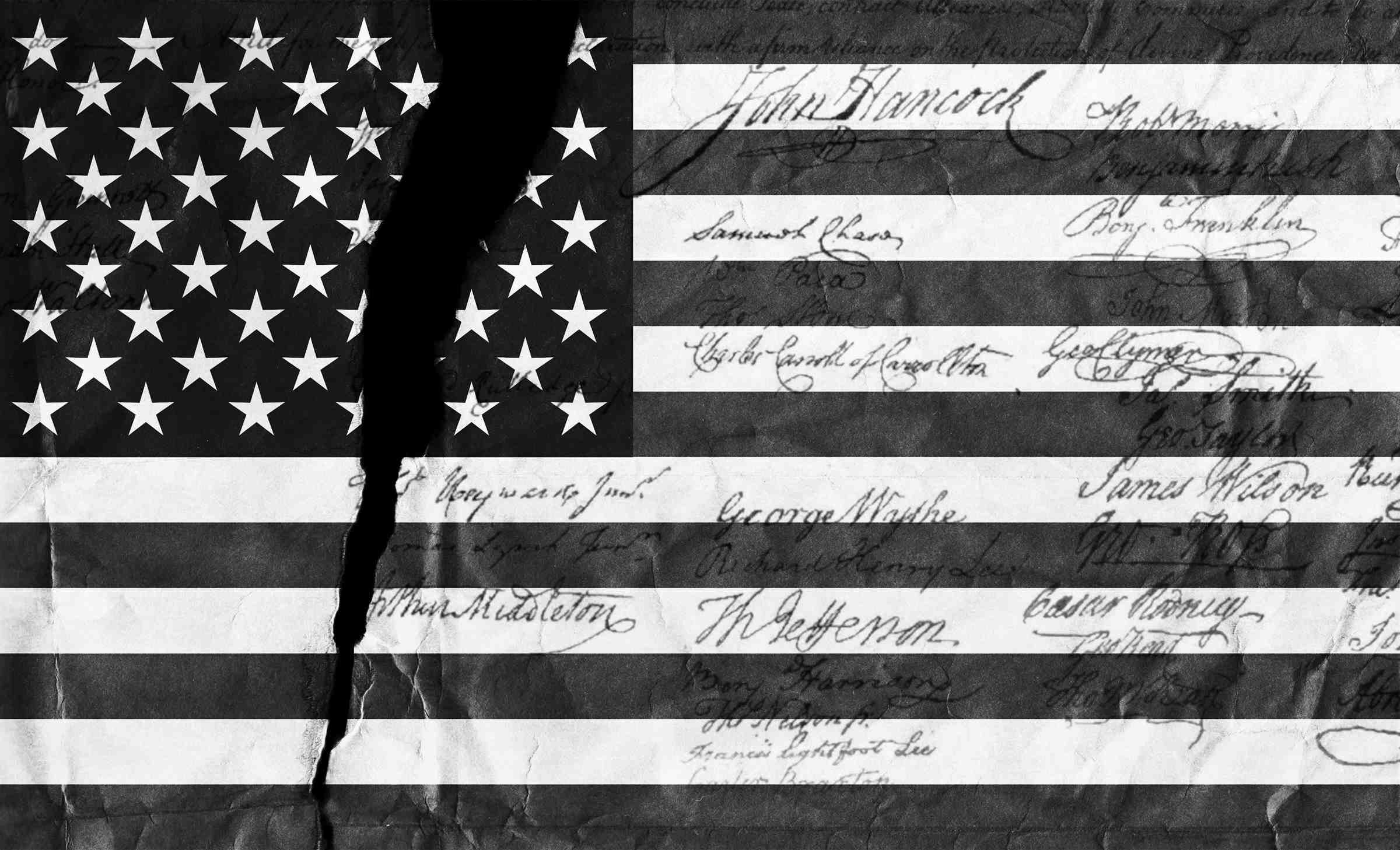

The Greenwood neighborhood of Tulsa, OK in flames during the 1921 massacre

Alvin C. Krupnick Co., Library of Congress

Terrorism, even if we refuse to acknowledge it

The largest terrorist attack in Oklahoma was not at the Federal Building in Oklahoma City in 1995. It was down the road in Tulsa in 1921. The Greenwood neighborhood of Tulsa, Oklahoma, was unique. In the early 20th century, it was referred to as “Black Wall Street” and was home to Black and Native Americans who had become wealthy from oil discoveries.

Wealth, however, did not mean equality. White residents were disturbed by the growing black wealth and sought to impose official segregation measures. In 1914, Tulsa passed a law that forbade anyone from living on a block where more than three quarters of the preexisting residents were of another race. In isolation, Greenwood thrived. Its main strip boasted attorneys’ offices, auto shops, cafes, a movie theater, funeral homes, pool halls, beauty salons, grocery stores, furriers, and confectioneries.

The resentment among whites against this community was a powder keg awaiting a spark. That spark came with a sexual assault allegation against a Black teenager named Dick Rowland. What happened in the elevator of the Drexel Building on May 30, 1921, is unclear, but the common narrative is that Rowland accidentally tripped against its operator, a white 17-year-old named Sarah Page, causing her to scream. A bystander who heard the scream called the police, and “like a game of telephone, the story became more inflammatory with each retelling, and spread rapidly,” writes Dexter Mullins. A Black man took his life into his hands if there was even the suggestion of interest in or offense against a white woman.

What we choose to remember speaks volumes.

When Rowland was captured, some Black World War I veterans from Greenwood armed themselves in front of the courthouse to prevent a lynching. They were justified in their fear — a lynching occurred in Tulsa the year before. Greenwood’s Black newspaper, The Tulsa Star, reported the August 1920 lynching of a white teenager accused of murder by a white mob. The paper reported that the Tulsa police had done little to protect the lynching victim, who had been taken from his jail cell at the county courthouse.

In front of the courthouse, a group of white men approached the Black men from Greenwood. “Nigger, what are you going to do with that pistol?” one of the white men asked. “I’m going to use it if I need to,” was the reply. The white man grabbed for the gun, and a gunshot rang out. It’s unclear whether it was accidental, a warning shot, or an attempt to injure or kill. In any case, all hell broke loose.

Tulsa newspaper with coverage of the massacre

Tulsa Daily World, Library of Congress

The groups of white and Black men had a running gunfight all the way to Greenwood. When they got there, the group of whites — which had grown in number — began firing indiscriminately on Black bystanders. Black people were shot in the streets and dragged behind cars with nooses tied around their necks. Then came the airplanes.

“I could see planes circling in mid-air,” Buck Colbert Franklin, a Black lawyer in Tulsa, recounted. “They grew in number and hummed, darted and dipped low. I could hear something like hail falling upon the top of my office building.” He looked out the window. "Down East Archer, I saw the old Mid-Way hotel on fire, burning from its top, and then another and another and another building began to burn from their top,” he said, describing the aerial bombardment of Greenwood. “The sidewalks were covered with burning turpentine balls. I knew all too well where they came from.” Black people fleeing from burning homes were machine-gunned down in the street.

“Tulsa civic leaders clung to conservative estimates,” writes historian Tim Madigan, but “the number of the dead no doubt climbed well into the hundreds, making the burning in Tulsa the deadliest domestic American outbreak since the Civil War.” Maurice Willows, an American Red Cross social worker, wrote the 1921 report of the aid society on their activities during and after the violence. He reported that up to 300 blacks were killed. He described the numerous stations in the city set up by the Red Cross to aid the wounded. He also reported that in the rush to bury the bodies, no records were made of many burials.

The Tulsa Massacre destroyed more than 35 blocks of the city, along with more than 1,200 homes and left some 300 people dead, mostly Black. Ten thousand people were left homeless. Yet this act of domestic terrorism is rarely mentioned or taught in schools. What we choose to remember speaks volumes.

The battle of Antietam: Charge of Burnside 9th Corps on the right flank of the Confederate Army

Edwin Forbes, Library of Congress

A war fought for slavery

Research conducted by the Southern Poverty Law Center in 2017 shows that our schools are failing to teach the truth about African enslavement. Only 8 percent of high school seniors surveyed can identify slavery as the central cause of the Civil War. Two-thirds (68 percent) don’t know that it took a constitutional amendment to formally end slavery. Fewer than one in four students (22 percent) can correctly identify how provisions in the Constitution gave advantages to slaveholders. The truth is clear if we choose to see it.

By 1860, America had 4 million slaves worth a total of $3 billion of the day’s currency.

David Blight has written that the total value of all slaves combined, as property, in 1860 was greater than the value of every bank, factory, and railroad in the U.S. By 1860, America had 4 million slaves worth a total of $3 billion of the day’s currency. As a result, there were more millionaires in the Mississippi Valley — notably one of the poorest parts of America today — than anywhere else in the nation.

Furthermore, the southern states were absolutely clear about why they left the union:

- Texas – “[A]ll white men are and of right ought to be entitled to equal civil and political rights; that the servitude of the African race, as existing in the states, is mutually beneficial to both bond and free and is abundantly authorized and justified by the experience of mankind and the revealed will of the Almighty Creator....”

- Mississippi – “[O]ur position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery-the greatest material interest of the world... A blow at slavery is a blow at commerce and civilization.”

- Louisiana –“[T]he people of the slaveholding states are bound together by the same necessity and determination to preserve African slavery.”

- Florida secessionists – “At the South, and with our People of course, slavery is the element of all value, and the destruction of that destroys all that is property.”

- Georgia – “For the last ten years we have had numerous and serious causes of complaint against our non-slave-holding confederate States with reference to the subject of African slavery. They have endeavored to weaken our security, to disturb our domestic peace and tranquility, and persistently refused to comply with their express constitutional obligations to us in reference to that property…”

Vice President Alexander H. Stephens of the Confederacy, in his 1861 “Cornerstone speech,” was as clear as he could possibly be: “Our new government is founded upon… the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition.”

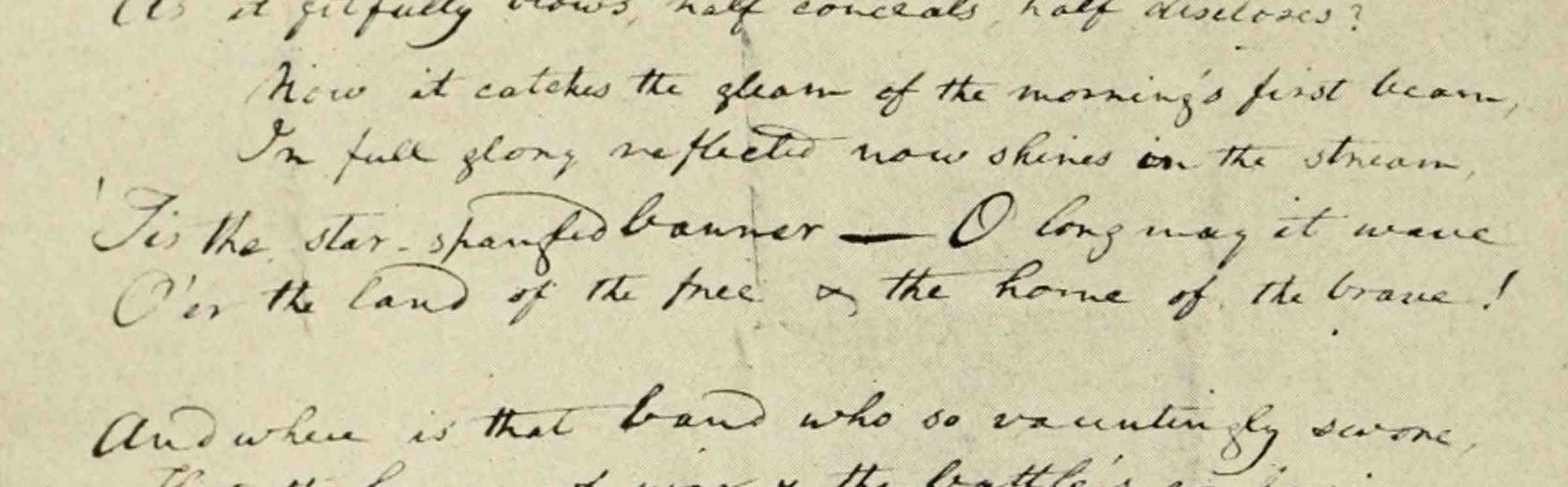

Francis Scott Key's original manuscript copy of his "Star-Spangled Banner" poem.

Francis Scott Key was an avowed white supremacist

The third verse of the national anthem celebrates the murder of slaves: “No refuge could save the hireling and slave from the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave…” Some claim Key was referring to whites captured by the British who were forced to fight for them. There is no historical evidence to support this claim, and facts about Key make it unlikely.

Key came from a rich slave-owning family in Maryland. Just weeks before he wrote the national anthem, Key saw the Colonial Marines — Black slaves who fought for the British in the War of 1812 — help the British drive American soldiers back to Washington, D.C., and then set the White House on fire. He said Blacks were, “a distinct and inferior race of people, which experience proves to be the greatest evil that afflicts the community.”

As the prosecutor in Washington, D.C., he sought the death penalty for a man who possessed abolitionist literature arguing to the jury: “Are you willing gentlemen, to abandon your country, to permit it to be taken from you and occupied by the abolitionist, according to whose taste it is to associate and amalgamate with the Negro?”

Reparations for slavery have already been paid

On April 16, 1862, more than eight months before he issued his Emancipation Proclamation, Abraham Lincoln signed a bill ending slavery in the District of Columbia. It provided for immediate emancipation of slaves and compensation to slave owners loyal to the Union of up to $300 for each freed slave. Over the next nine months, the board of commissioners appointed to administer the act approved petitions, completely or in part, from former owners for the freedom of 2,989 former slaves. Lincoln’s administration paid about $1 million to slave owners in D.C. for the loss of property.

If you didn’t know some of these facts before reading them here, what else don’t you know about the hidden truths of Black American history?