Cell Phone Location Tracking Public Records Request

What's at Stake

Of all of the recent technological developments that have expanded the surveillance capabilities of law enforcement agencies at the expense of individual privacy, perhaps the most powerful is cell phone location tracking. And now, after an unprecedented records request by ACLU affiliates around the country, we know that this method is widespread and often used without adequate regard for constitutional protections, judicial oversight, or accountability.

Summary

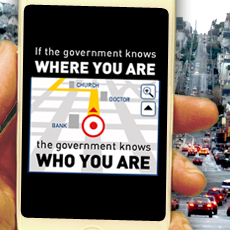

All cell phones register their location with cell phone networks several times a minute, and this function cannot be turned off while the phone is getting a wireless signal. The threat to personal privacy presented by this technology is breathtaking.

To know a person's location over time is to know a great deal about who a person is and what he or she values. As the federal appeals court in Washington, D.C. explained:

TAKE ACTION

Tell Congress: Support the GPS Act! »

MAP: Is Your Local Law Enforcement Tracking Your Cell Phone's Location?

MORE

What our Public Records Act Requests Sought »

"A person who knows all of another's travels can deduce whether he is a weekly church goer, a heavy drinker, a regular at the gym, an unfaithful husband, an outpatient receiving medical treatment, an associate of particular individuals or political groups — and not just one such fact about a person, but all such facts."

The government should have to obtain a warrant based upon probable cause before tracking cell phones. That is what is necessary to protect Americans' privacy, and it is also what is required under the Constitution. (In certain emergency situations, for example to locate a missing person, tracking a cell phone without a warrant is acceptable).

In United States v. Jones, a majority of the Supreme Court recently concluded that the government conducts a search under the Fourth Amendment when it attaches a GPS device to a car and tracks its movements. The conclusion should be no different when the government tracks people through their cell phones, and in both cases a warrant and probable cause should be required.

Until now, how law enforcement agents use cell phone tracking has been largely shrouded in secrecy. What little was known suggested that law enforcement agents frequently tracked cell phones without obtaining a warrant based on probable cause.

In August 2011, 35 ACLU affiliates filed over 380 public records requests with state and local law enforcement agencies to ask about their policies, procedures and practices for tracking cell phones. In April 2012, an additional affiliate filed 27 requests.

What we have learned is disturbing. While virtually all of the roughly 250 police departments that responded to our request said they track cell phones, only a tiny minority reported consistently obtaining a warrant and demonstrating probable cause to do so. While that result is of great concern, it also shows that a warrant requirement is a completely reasonable and workable policy.

The government's location tracking policies should be clear, uniform, and protective of privacy, but instead are in a state of chaos, with agencies in different towns following different rules — or in some cases, having no rules at all. It is time for Americans to take back their privacy. Courts should require a warrant based upon probable cause when law enforcement agencies wish to track cell phones. State legislatures and Congress should update obsolete electronic privacy laws to make clear that law enforcement agents should track cell phones only with a warrant.

Below is an overview of our findings and recommendations.

The Documents: The Government Is Routinely Violating Americans' Privacy Rights Through Warrantless Cell Phone Tracking

The ACLU received over 5,700 pages of documents from roughly 250 local law enforcement agencies regarding cell phone tracking. The responses show that while cell phone tracking is routine, few agencies consistently obtain warrants. Importantly, however, some agencies do obtain warrants, showing that law enforcement agencies can protect Americans' privacy while also meeting law enforcement needs.

The government responses varied widely, and many agencies did not respond at all. The documents included statements of policy, memos, police requests to cell phone companies (sometimes in the form of a subpoena or warrant), and invoices and manuals from cell phone companies explaining their procedures and prices for turning over the location data.

The overwhelming majority of the roughly 250 law enforcement agencies that provided documents engaged in at least some cell phone tracking — and many track cell phones quite frequently. Most law enforcement agencies explained that they track cell phones to investigate crimes. Some said they tracked cell phones only in emergencies, for example to locate a missing person. Only 13 said they have never tracked cell phones.

Many law enforcement agencies track cell phones quite frequently. For example, based on invoices from cell phone companies, it appears that Raleigh, N.C. tracks hundreds of cell phones a year. The practice is so common that cell phone companies have manuals for police explaining what data the companies store, how much they charge police to access that data, and what officers need to do to get it.

Most law enforcement agencies do not obtain a warrant to track cell phones, but some do, and the legal standards used vary widely. Some police departments protect privacy by obtaining a warrant based upon probable cause when tracking cell phones. For example, police in the Riverside County, CA, Denver, the County of Hawaii, Wichita, and Lexington, Ky. demonstrate probable cause and obtain a warrant when tracking cell phones. If these police departments can protect both public safety and privacy by meeting the warrant and probable cause requirements, then surely other agencies can as well.

Unfortunately, other departments do not always demonstrate probable cause and obtain a warrant when tracking cell phones. For example, police in Lincoln, Neb. obtain even GPS location data, which is more precise than cell tower location information, on telephones without demonstrating probable cause. Police in Wilson County, N.C. obtain historical cell tracking data where it is "relevant and material" to an ongoing investigation, a standard lower than probable cause.

Police use various methods to track cell phones. Most commonly, law enforcement agencies obtain cell phone records about one person from a cell phone carrier. However, some police departments, like in Gilbert, Ariz., have purchased their own cell tracking technology.

Sometimes, law enforcement agencies obtainall of the cell phone numbers at a particular location at a particular time. For example, a law enforcement agent in Tucson, Ariz. prepared a memo for fellow officers explaining how to obtain this data. And records from Cary, N.C. include a request for all phones that utilized particular cell phone towers.

Cell phone companies have worsened the lack of transparency by law enforcement by hiding how long they store location data. Cell phone companies store customers'location data for a very long time. According to the U.S. Department of Justice, Sprint keeps location tracking records for 18-24 months, and AT&T holds onto them "since July 2008," suggesting they are stored indefinitely. Yet none of the major cell phone providers disclose to their customers the length of time they keep their customers' cell tracking data. Mobile carriers owe it to their customers to be more forthright about what they are doing with our data.

>>ACLU Open Letter to Wireless Carriers on Location Tracking of Cell Phones

Click here for detailed findings and analysis of the ACLU's cell phone tracking records requests »

The Solutions: What Can Be Done to Protect Privacy

Cell phone location data is not the sort of information that law enforcement agents should be obtaining without the safeguard of the probable cause standard and review by a judge. That will ensure that legitimate investigations can proceed, while protecting innocent Americans from unjustified invasions of their privacy.

State and federal lawmakers should pass laws requiring a warrant for police to engage in location tracking in non-emergency situations. In Congress, there are two pending efforts: First, bipartisan legislation, entitled the Geolocation Privacy and Surveillance (GPS) Act, is sponsored in the Senate by Senators Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) and Mark Kirk (R-Ill.) and in the House by Representatives Jason Chaffetz (R-Utah), Peter Welch (D-Vt.) and Jim Sensenbrenner (R-Wisc.). The bills would require law enforcement agents to obtain a warrant in order to access location information.

The other effort is part of Democratic Vermont Senator Patrick Leahy's proposal to update the 1986 Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA), which the government also uses to secretly access people's email accounts. The bill includes a warrant requirement for real-time tracking, but not for historical location information.

TAKE ACTION: Ask Congress to update ECPA today »

In the meantime, more local law enforcement agencies should voluntarily follow the lead of those police departments that already require a warrant and probable cause to track cell phones.

And more states should pass laws requiring their law enforcement agents to obtain a warrant and probable cause to track cell phones.

When they have the opportunity, more judges should follow the leads of those judges who have required the government to obtain a warrant based upon probable cause.

Technology is evolving quickly, and often to the detriment of privacy. But how much privacy Americans enjoy is fundamentally a choice that ultimately is ours as a society to make.

Legal Documents

-

07/18/2012

ACLU FOIA Request for FBI Memos re: United States v. Jones GPS Tracking Case

Date Filed: 07/18/2012

Download DocumentPress Releases

ACLU Releases Cell Phone Tracking Documents From Some 200 Police Departments Nationwide

ACLU Seeks Details on Government Mobile Phone Tracking in Massive Nationwide Information Request