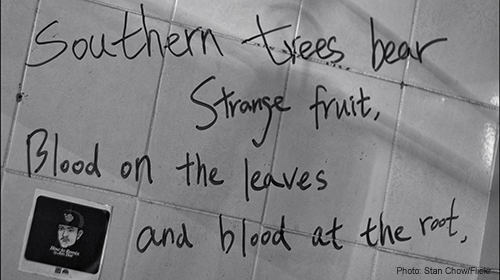

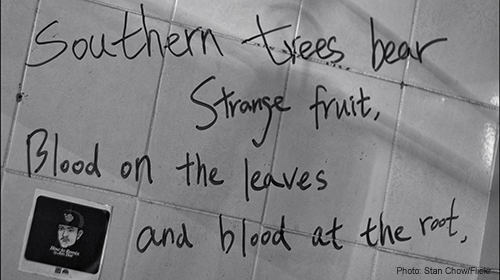

Replacing the Noose With a Needle: The Legacy of Lynching in the United States

Ida B. Wells said it best, "Our country's national crime is lynching."

Last week, we were reminded of this when the Equal Justice Initiative released its report, "Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror." A gruesome history of these carnivals of torture and death from the Civil War until World War II, the report documents the racial terrorism designed to keep black Americans across the South destitute and powerless.

As I read EJI's report, my mind immediately went back to an interview Alex Kozinski, the chief judge of the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, gave to the Los Angeles Times last summer. The interview was stark evidence of our failure to recognize how race distorts our criminal justice system up until the present day. I cringed at the following exchange:

Why have most other Western countries abolished the death penalty?

Most of these countries have in their recent past abused it. I'm not really surprised or unhappy that Germany has outlawed the death penalty. They sort of misused it within living memory, so they probably ought not to be trusted to have one…. In this country by and large we've had executions done with due process. We've had a sad history of lynchings in the South, but in the Wild West they had trials, some measure of due process. It's not that we're guilt-free, but we have less to account for than other countries.

That is clearly not the case as EJI shows in ghastly detail. Lynchings cannot be dismissed as a footnote to our criminal justice system. They were cruel, widespread, hate-driven acts of terrorism, with an enormous social cost we're still paying for today.

Until the 1950s, lynchings were advertised and attended like they were state fairs. People came from all around to witness the torture, humiliation, and murder of human beings. Individuals purchased lynching postcards and traded them like baseball cards. Children were permitted to attend the "show," to watch the mutilation of another person. Photos were taken, souvenirs gathered from the chopped, charred, and often castrated bodies.

EJI documented 3,949 racial terror lynchings of African-Americans between 1877 and 1950 across 12 southern states, including an additional 700 lynchings that were previously unknown. Georgia and Mississippi had the highest number of verifiable lynchings of African-Americans – 586 and 576, respectively. We will never know how many African-Americans disappeared into the night, never to be seen again. Clearly, what we do know belies the suggestion that that America has "less to account for than other countries."

If we are to ever fix our broken criminal justice system, we must first acknowledge the baggage it carries.

This must begin with acknowledgement of our torrid, bloody history of executions without a semblance of due process. Lynchings were a method of organized, socially accepted extra-judicial violence that terrorized millions of African-Americans across the South for nearly a century. We also need to be honest that no one has ever been held accountable for these horrific crimes. No white person was ever convicted for the lynching of an African-American during the period covered in the study.

And yet the unjust execution of African-American men thrives today on the same soil as the lynching trees: Only now the noose has been replaced with the needle. African-American men are over-represented on death row, in executions, and in exonerations. To boot, African-American jurors are systematically excluded by prosecutors in jury service. Race is one of the most disturbing explanations for innocent men, like Glenn Ford in Louisiana and Henry MCollum in North Carolina, ending up on death row for crimes they did not commit.

We cannot continue to ignore the racial injustice of our death penalty system, past or present. I do agree with one comment made by Judge Kozinski, "we ought to come face to face with what we're doing. If we're not comfortable with what we're doing we should not be doing it."

It's time to get uncomfortable.

Learn more about the death penalty and racial justice and other civil liberty issues: Sign up for breaking news alerts, follow us on Twitter, and like us on Facebook.