How the ACLU Won the Largest Mass Acquittal in American History

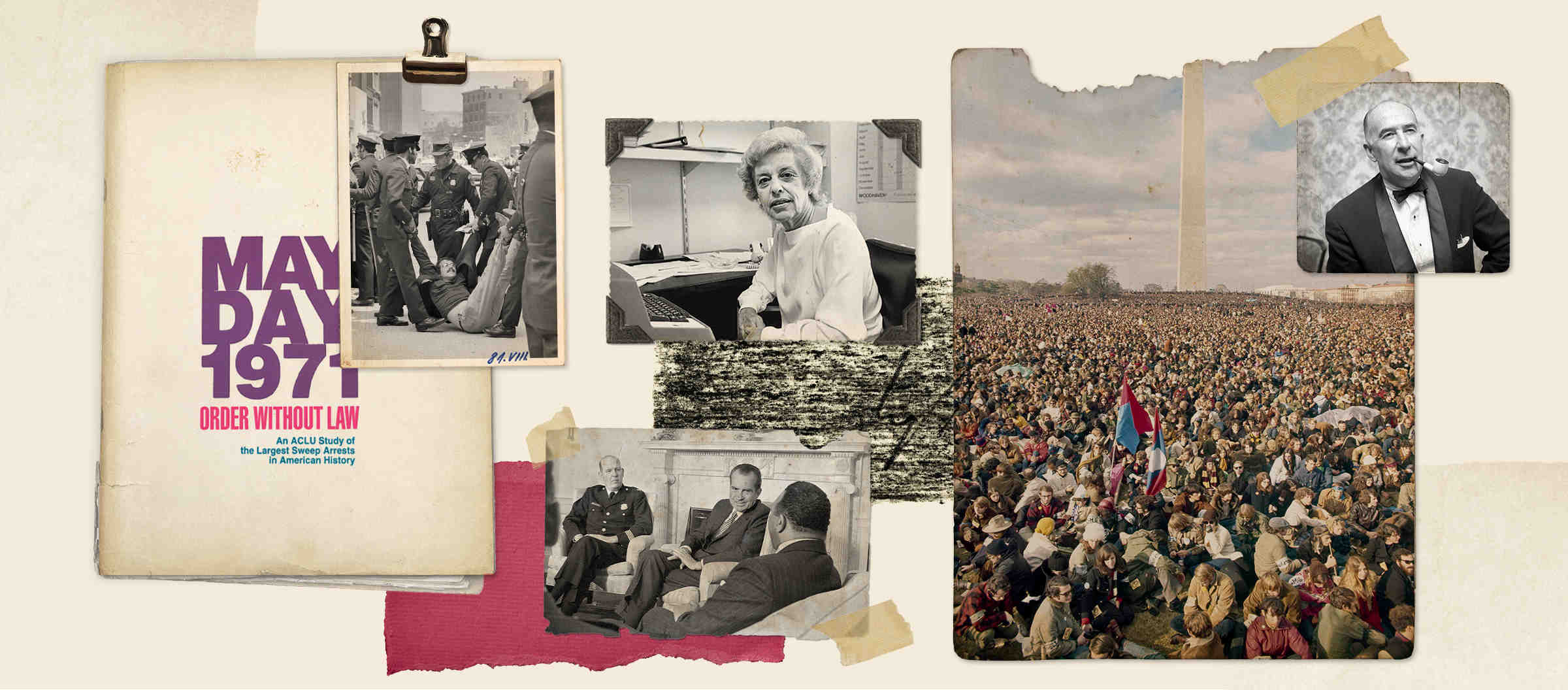

Thousands of anti-war protesters gather near the Washington Monument in Washington, D.C., May 3, 1971, one of several days of civil disobedience called the Mayday march on Washington.

AP Photo

On Saturday, May 1, 1971, about 35,000 opponents of the Vietnam War assembled in Washington, D.C., camping out in West Potomac Park near the Lincoln Memorial and the Washington Monument. Led by antiwar protesters who called themselves the Mayday Tribe, the goal of the demonstrations was simple: “If the government won’t stop the war, we’ll stop the government.” On Monday, May 3, according to the group, thousands upon thousands of protesters would fan out across the capital at strategic interactions and bridges to create gridlock in the city and stop federal employees from getting to work.

The protests, however, were a failure. The Nixon administration was ready.

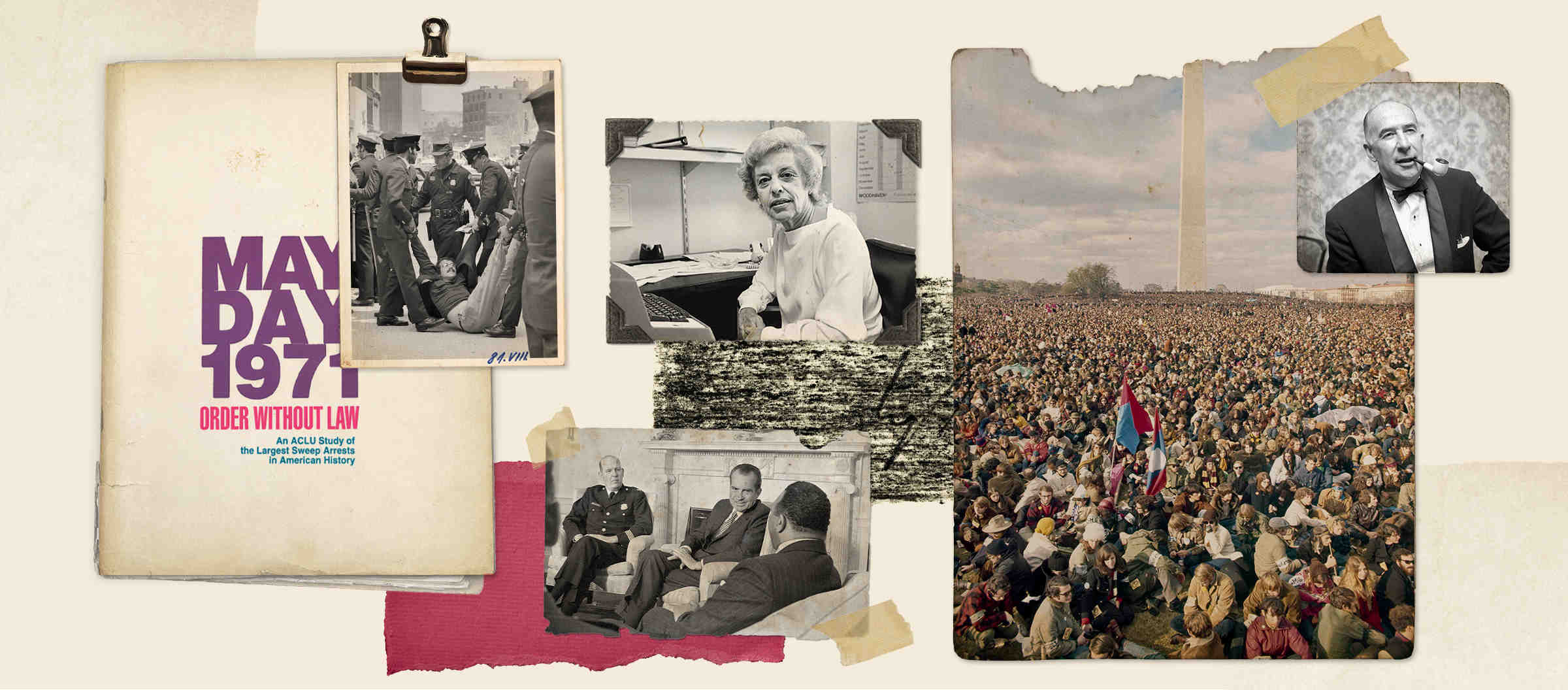

Under the direction of Attorney General John Mitchell, the administration orchestrated a massive police-military response to disrupt the protests. By Saturday night, the Defense Department had staged thousands of armed federal troops around the capital’s suburbs and ordered in a military police battalion as well as a helicopter battalion. In the city, over 5,000 police officers were on duty, backed up by 1,400 National Guardsmen.

U.S. Attorney General John Mitchell is shown February 10, 1970

AP Photo/DP

Early Sunday morning just after dawn, the government pounced on the protesters in West Potomac Park. The administration canceled a permit for use of the park and sent riot police in firing tear gas to scatter tens of thousands of protesters. A Justice Department official, William Rehnquist, who was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court by Nixon not long afterward, described the government’s actions as the imposition of “qualified martial law.”

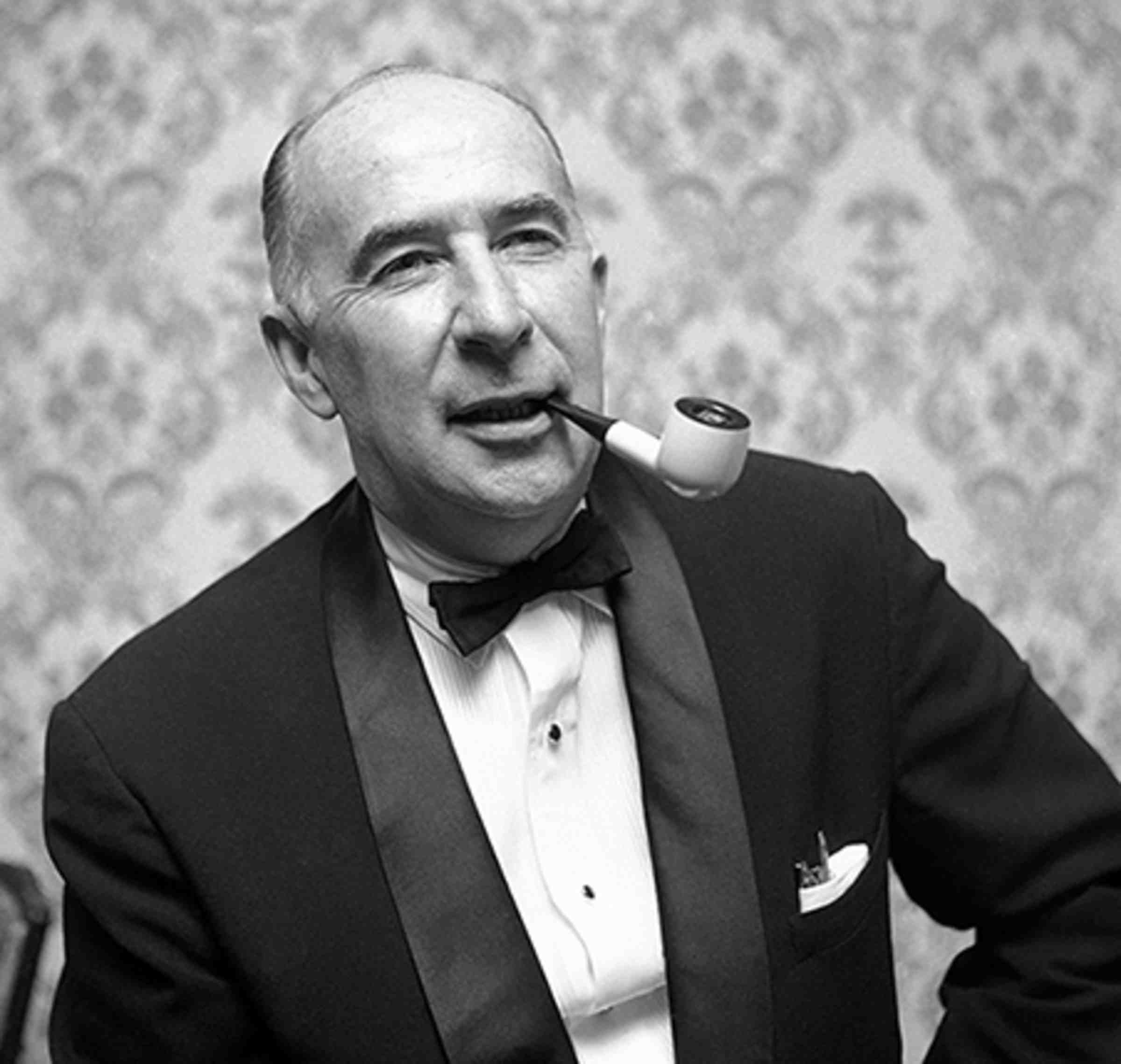

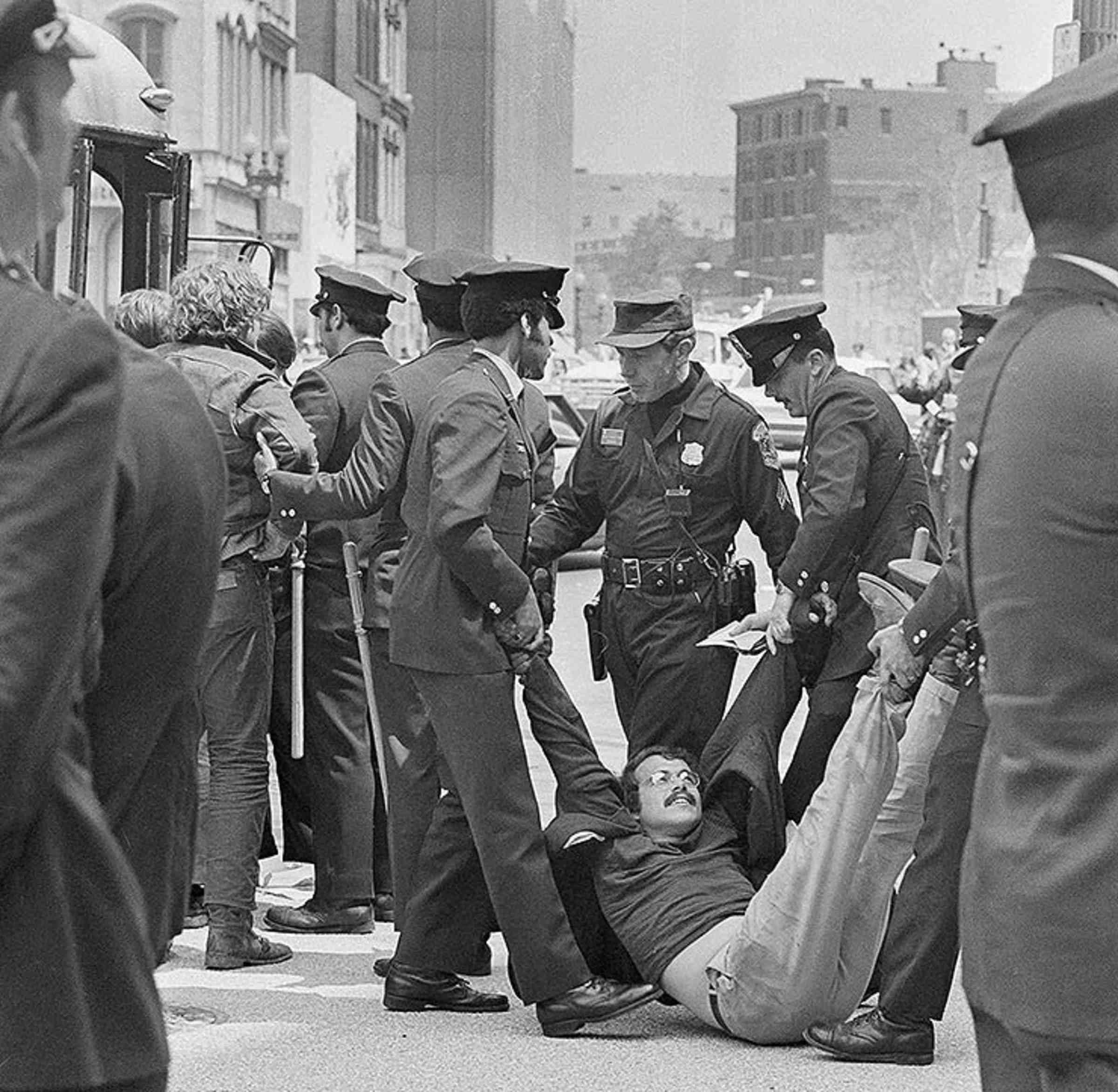

An anti-war demonstrator is frisked by a Washington policeman as mass arrests were made of protesters during a several days-long act of civil disobedience in Washington, D.C., May 2, 1971.

AP Photo

Many of the protesters fled to universities, churches, and other locations across the city to regroup for the next day’s act of civil disobedience.

On Monday morning, the demonstrators still in Washington attempted to carry out their planned action across the city. They were met immediately by police, who in the words of The New York Times, “dispersed the demonstrators with nightsticks and tear gas.” Between 8:30 a.m. and 9 a.m., six Army Chinook helicopters started landing near the Washington Monument off-loading nearly 200 armed soldiers of the 82nd Airborne Division. Officers went through the streets arresting anybody they could find who seemed to be an opponent of the war.

“Anyone and everyone who looked at all freaky,” said one protester, “was scooped up off the street.” They even swept up some construction workers who had gone out on the streets to support the government as well as elderly people in their 70s and children as young as 12. By the end of the day, over 7,000 people would be arrested in the largest mass arrest in U.S. history. All told, the May Day protests would result in more than 12,000 people arrested in dragnet sweeps by the police by the end of Tuesday, May 4.

Police carry off an anti-war demonstrator from an entrance to the Justice Department in Washington, D.C., April 30, 1971.

AP Photo

Given the great numbers of persons arrested on Monday, there were far too many to confine in local jails. City police then began sending the arrested to the fenced-in, open-air practice field of the Washington Redskins’ football team near Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Stadium. Described by detained protesters as a “concentration camp,” the protesters were held without food, water, or sanitary facilities. Protesters dug a latrine and shielded it with tarps for privacy. Inside RFK stadium, a battalion of the 82nd Airborne stood ready to deploy if the police and National Guardsmen couldn’t control the detainees.

This was the scene in Washington, D.C., on May 3, 1971, after a great number of anti-war protesters were arrested and housed on the football practice field of the Washington Redskins. One sat on the goalpost in the background, which was torn down. Note bulge in fence caused by crush of protesters against it after their arrests.

AP Photo

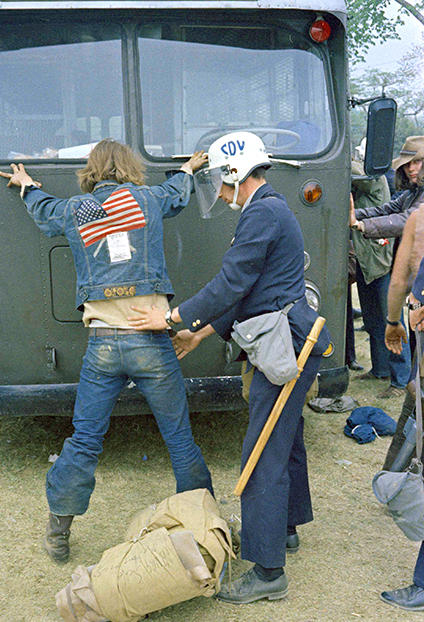

That morning, I got a call in the ACLU’s national office from Florence Isbell, the executive director of the National Capital Area Civil Liberties Union, and the ACLU affiliate’s legal director, Ralph Temple. Ralph and Florence were seeking my advice on how to deal with the Nixon administration’s unprecedented crackdown on free assembly as well as its systematic violation of people’s due process rights through indiscriminate mass arrests. And it just happened to be the case that I had my own experiences with mass arrests of anti-war demonstrators in New York City just a few years earlier when I was the director of the New York Civil Liberties Union. Those experiences proved critical in helping Ralph, Florence, and the D.C. affiliate achieve the largest mass acquittal in American history.

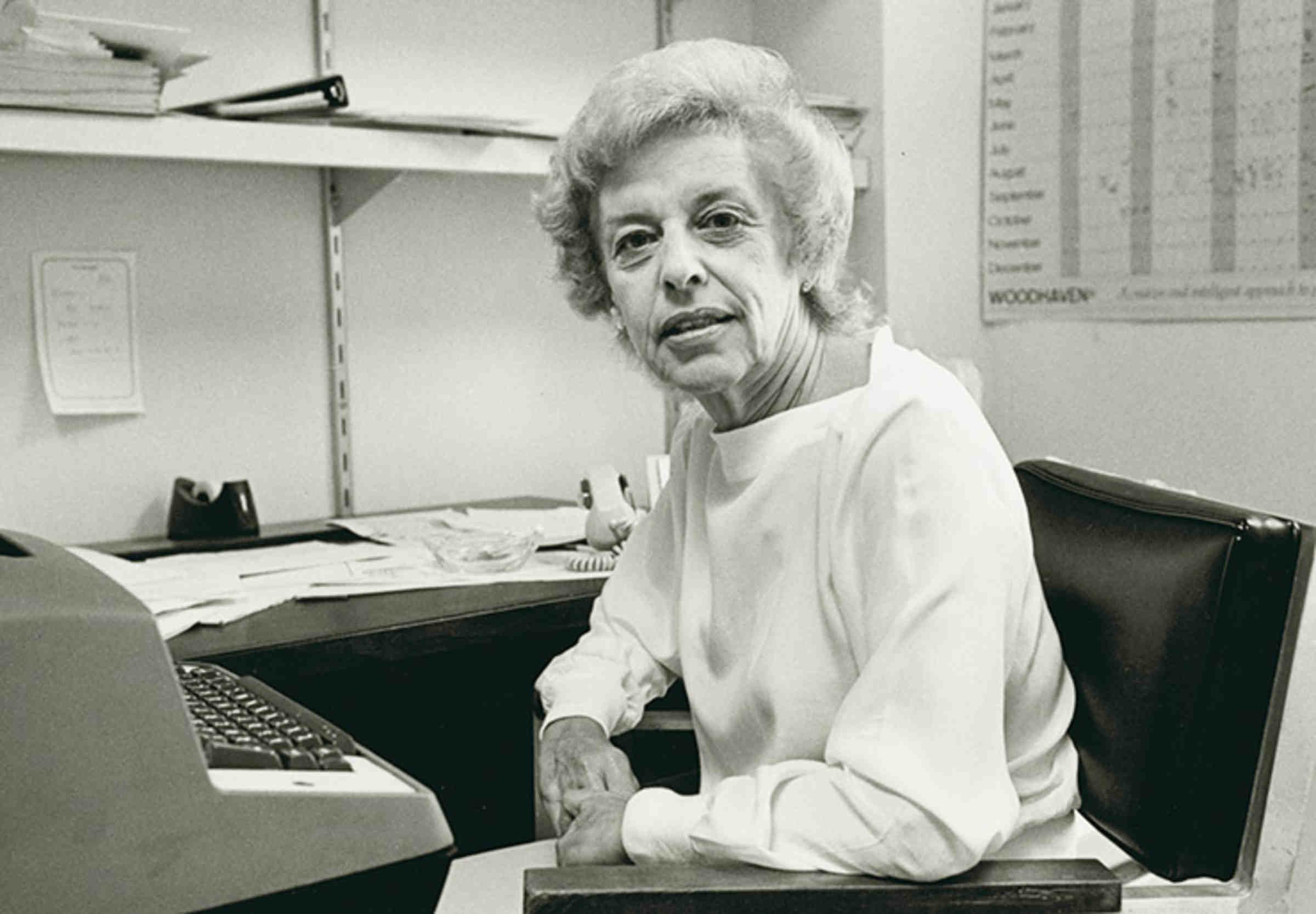

ACLU Associate Director Florence Isbell sitting at her desk, 1984

ACLU Archives, Lawrence Frank

Lying Under Oath

In New York in the 1960s, the New York Civil Liberties Union had observed that when mass arrests took place, the police hustled those they arrested into vans and then went off to make additional arrests. They neither took the time to secure identification of the persons they arrested nor write down the conduct they had observed which supposedly justified the arrests. That meant that when trials took place, the police who testified against defendants made up stories in order to justify the arrests. In other words, they lied under oath.

At NYCLU, we tested our observations on an occasion when we anticipated that a large number of arrests would be made. Knowing the route that the anti-war demonstrators proposed to take during a December 1967 protest in lower Manhattan, we posted observers along the route with movie cameras to record what took place. In a period when many New Yorkers opposed the war, we had little difficulty in persuading shop owners and others to allow us to post our observers in places where they could film the action without themselves becoming targets of the police.

Read the Entire ACLU 100 History Series

Source: American Civil Liberties Union

The attorney who directed the Police Practices Project of the New York Civil Liberties Union, Paul Chevigny, affixed a Moviola to his desk. This was a device used in the editing of films that allows frame-by-frame examination. The films we examined made it clear not only that the allegations against individual arrestees were false, but they also proved that the police officers who were identified in court as the arresting officers were not those who actually made the arrests for which they claimed to be witnesses. The way the police sought to secure criminal convictions of many hundreds of anti-war demonstrators was by perjuring themselves.

We conducted a small number of trials in which we severely embarrassed the police and the prosecutors who were relying on their testimony. After that, we met with the prosecutors and disclosed to them how much evidence we had of police perjury. The prosecutors had no choice but to dismiss the rest of the cases, about 600 on that occasion.

Author and ACLU Executive Director Aryeh Neier, 1970.

ACLU Archives

A Massive Exercise in Perjury

When I spoke to Florence Isbell and Ralph Temple that Monday morning, I told them about these experiences and suggested that, given the great number of arrests in Washington, D.C., the police might do the same.

Florence and Ralph acted quickly. They contacted volunteer lawyers and got them to go to the outside detention camp near RFK Stadium. There the lawyers observed police circulating among the arrested demonstrators, collecting information on identities and arbitrarily assigning police as the supposed arresting officers. It was clear that this was to be a massive exercise in perjury.

Events would bear this out. In the early summer, the District of Columbia Human Relations Commission released a report that determined more than half the people arrested were innocent of any lawbreaking. The report noted that the criterion used by police to arrest people during the May Day actions was “evidence of youthfulness” not actual lawbreaking. The media was critical as well. “As it happened,” wrote a New York Times reporter in mid-May, “there is no doubt that the Washington police with the active connivance of the Department of Justice carried out a policy of preventative detention.”

The Nixon administration, unsurprisingly, continued to defend itself. Attorney General Mitchell would tell a conference of California police officers that “Washington’s decisive opposition to mob force will set an example for other communities” that should be replicated. President Nixon also dug in. “I approve of what [the police] did, and in the event that we have similar situations in the future, I hope that we can handle those situations as well as this one.”

The courts didn’t agree.

President Richard M. Nixon, center, talks with Washington's Police Chief Jerry Wilson, on the left, and Mayor Walter E. Washington, right, in his White House office, May 8, 1971, to personally thank them for handling recent anti-war demonstrations with "firmness and restraint."

AP Photo/Charles Tasnadi

The evidence collected by the National Capital Area ACLU’s volunteer lawyers made it possible to secure the acquittals of all but a small number — under a hundred — of the close to 13,000 anti-war demonstrators arrested during the first week of May 1971. It also contributed to a class action lawsuit that the ACLU affiliate filed against the Washington, D.C. police. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, which heard the case, would summarize critically the actions of D.C. police this way:

On May 3, 1971, when Washington, D.C., was confronted with a threat to bring the orderly conduct of the Federal government to a standstill, the public authorities responded by ordering mass arrests. There was no declaration of martial law. Yet the procedures for requiring that arrests be accompanied by some indication of the basis therefor — even as diluted by the special emergency arrangement permitting the arresting officer to establish probable cause for detention by preparing a simplified field arrest form and photograph — were terminated. The innocent as well as the guilty were in large numbers swept from the streets and placed in detention facilities.

That lawsuit provided one of the few instances in which anti-war demonstrators were able to collect monetary damages for their mistreatment. Some of the demonstrators contributed the modest sums they were awarded to the National Capital Area ACLU.

And that, of course, is what you call a happy ending given the lawlessness of the Nixon administration, which would eventually succumb to its corruption a few years later.

Aryeh Neier served on the staff of the ACLU from 1963 to 1978 and was national Executive Director from 1970 to 1978.