The Skokie Case: How I Came To Represent The Free Speech Rights Of Nazis

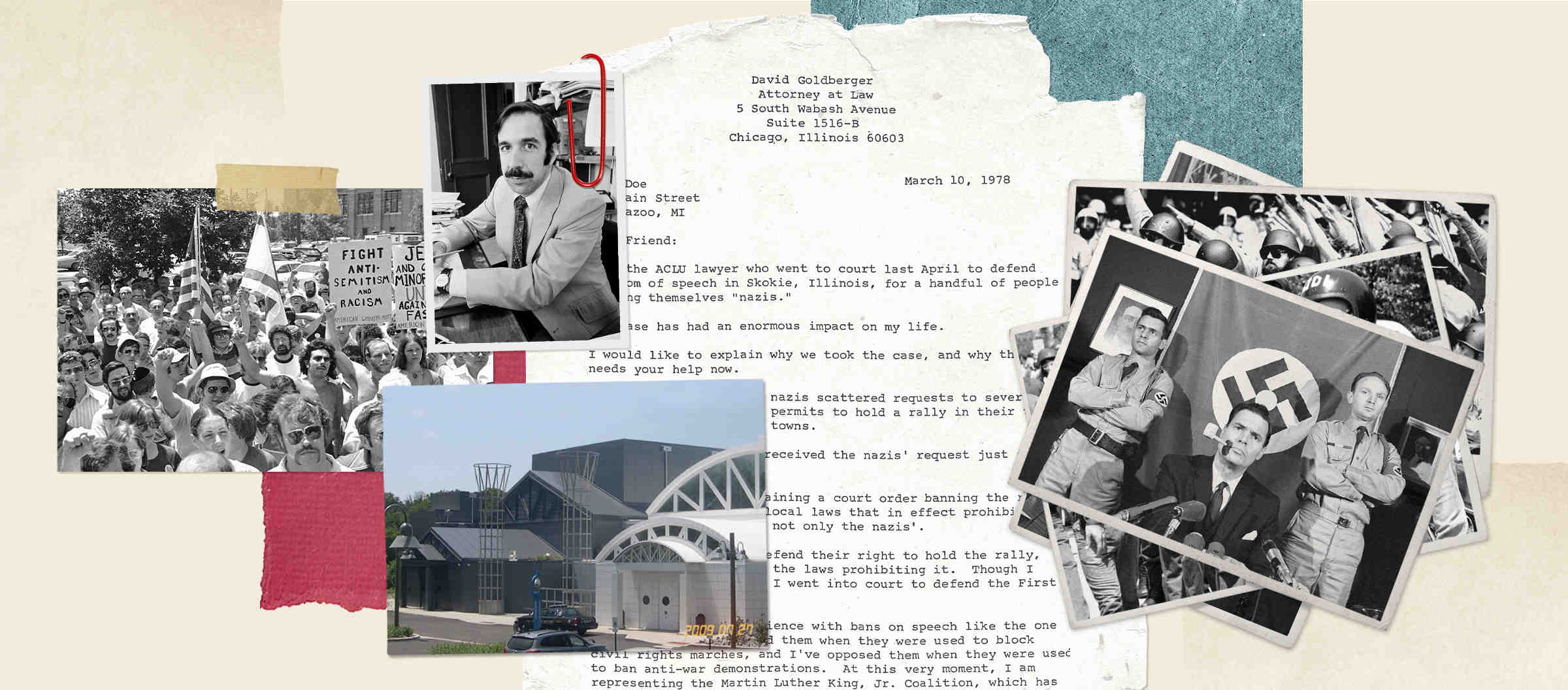

Author David Goldberger, photographed in his Chicago office, on April 19, 1979.

AP

About 50 years ago, I led a team of dedicated lawyers from the ACLU of Illinois in representing a group of Chicago-area Nazis who sought to hold a demonstration in downtown Skokie, Illinois. The Nazis’ decision to go to Skokie provoked a storm of outrage, because Skokie was a village that was nearly half Jewish and home to hundreds of Holocaust survivors. Skokie officials and their allies tried every possible legal device to block the demonstration, and their efforts triggered a barrage of lawsuits that quickly became known as “the Skokie case.”

The village’s determination to block the Nazi demonstration was so intense that it had the effect of turning the Skokie case into a landmark example of the vitality of the First Amendment, as well as the ACLU’s fierce commitment to the principle that freedom of speech is a universal right no matter how offensive the message or the speaker.

It all started on Wednesday, April 27, 1977, when I received a phone call from Frank Collin, the Nazi leader, a man who, by all outward appearances, seemed to be an ordinary person with no distinguishing features — until, of course, he launched into his racist and anti-Semitic diatribes. He said that he had just been served with a lawsuit filed by Skokie in state court seeking to block his group’s planned demonstration in the village the following Sunday. Skokie had scheduled a hearing for the next morning.

According to Collin, the demonstration was to consist of 25-50 party members demonstrating in front of the Skokie Village Hall. They were going to appear in Nazi uniforms with swastika armbands, carrying Nazi banners and signs with the words “Free Speech for White People.” Collin said they selected Skokie to protest decisions by Chicago-area park districts, including Skokie’s, barring them from holding a demonstration in Chicago area parks. The demonstration was to last for about 30 minutes, after which the Nazis would return to their headquarters on the south side of Chicago.

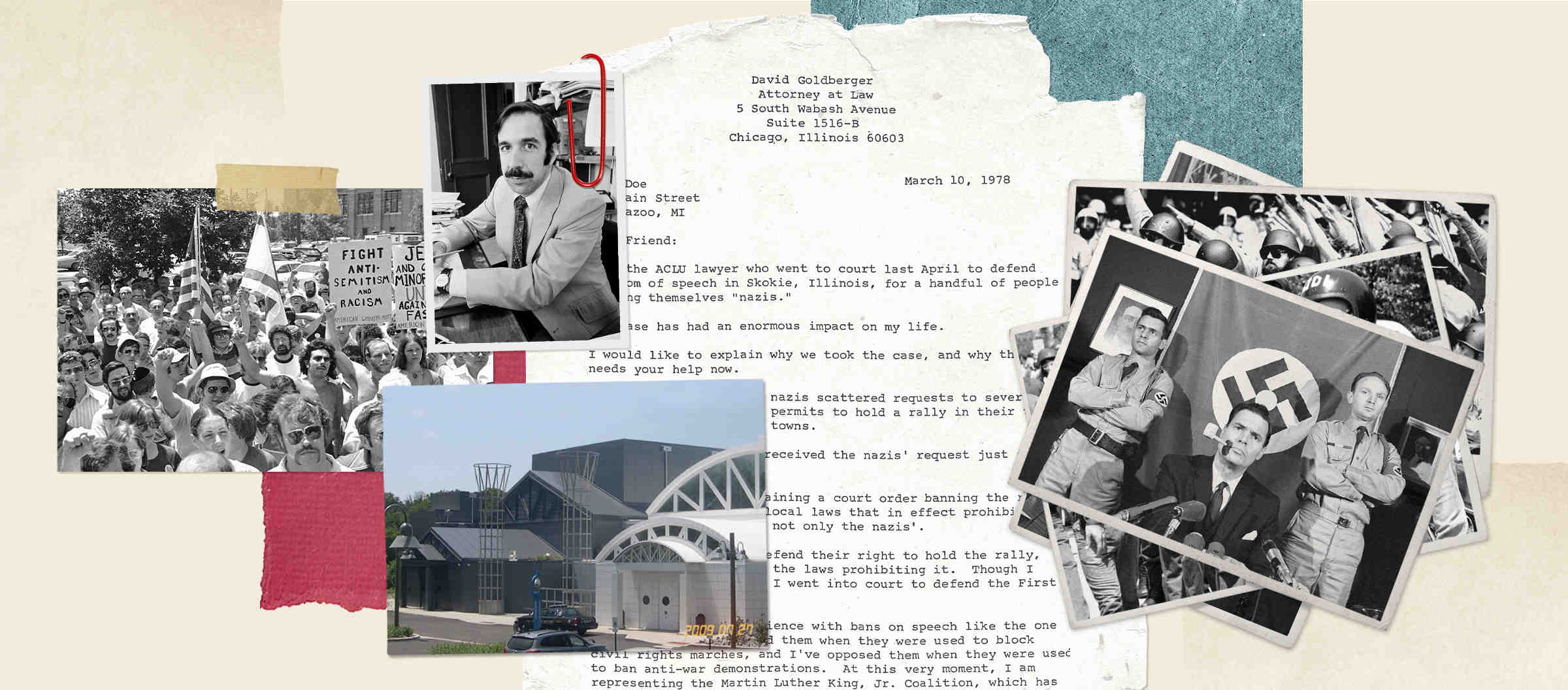

Nazi leader Frank Collin, right, shown in main room of ramshackle Chicago building that served as National Socialist Party headquarters in Chicago, July 20, 1977.

AP

No mention was made of the fact that I was Jewish, though my last name made that fact unmistakable. I later learned that that when members of the press questioned the Nazi leader about my religious background, he reportedly said that his primary concern was with successfully exercising his First Amendment rights, not the personal beliefs of his lawyers.

Skokie’s lawsuit was the first of multiple efforts to prevent the demonstration. It arose from implacable community opposition to allowing any Nazi to set foot in the village. The lawsuit was filed in spite of the initial advice of Skokie’s lawyers that the village should permit the Nazis to hold their brief demonstration, so that it would be over and quickly forgotten. Skokie’s Holocaust survivors were unpersuaded. They wanted the village to oppose the demonstration at all costs, and the members of the city council ultimately agreed.

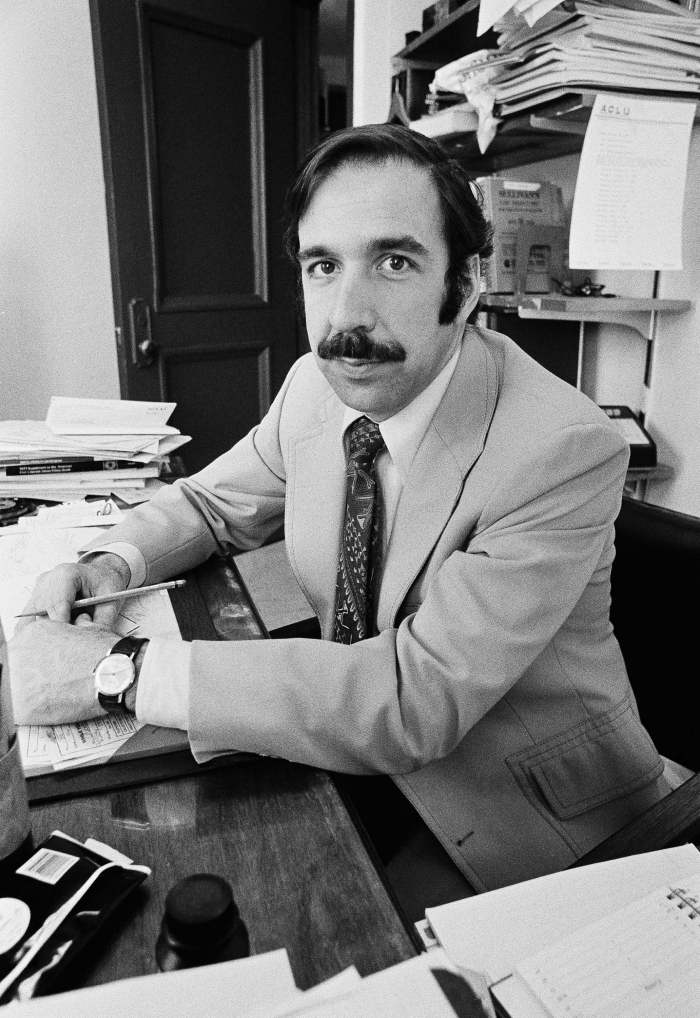

A large group of anti-Nazi demonstrators chant at a park in the predominantly Jewish Chicago suburb of Skokie, Illinois, July 4, 1977, protesting a possible future march in Skokie by Nazis.

AP

Everything that the village did in opposition to the assembly boiled down to the same thing: Skokie wanted what is known to lawyers as a “prior restraint” against any Nazi speech in Skokie. In non-technical language, this meant that Skokie wanted to find a way to stop the Nazis from speaking before they had a chance to articulate their message.

The First Amendment principles that apply to prior restraints are straightforward. While any effort to censor by punishing a speaker after the fact is likely to violate the First Amendment, preventing the speech ahead of time is even more likely to violate the Constitution, even where the anticipated speech is profoundly offensive and hateful. Central to the ACLU’s mission is the understanding that if the government can prevent lawful speech because it is offensive and hateful, then it can prevent any speech that it dislikes. In other words, the power to censor Nazis includes the power to censor protesters of all stripes and to prevent the press from publishing embarrassing facts and criticism that government officials label as “fake news.” Ironically, Skokie’s efforts to enjoin the Nazi demonstration replicated the efforts of Southern segregationist communities to enjoin civil rights marches led by Martin Luther King during the 1960s.

The Illinois ACLU’s decision to represent the Nazis came with an unexpected twist. Because I was the affiliate’s legal director, I had authority to undertake civil liberties cases that were clearly within ACLU policy, as this one was. In fact, the affiliate was familiar with Collin and his group. We were already representing him because the Chicago Park District was denying the Nazis permits to hold an assembly in any Chicago Park. I was also aware that in past years, the New York Civil Liberties Union had represented national Nazi leader George Lincoln Rockwell in his quest to hold an assembly in New York’s Central Park.

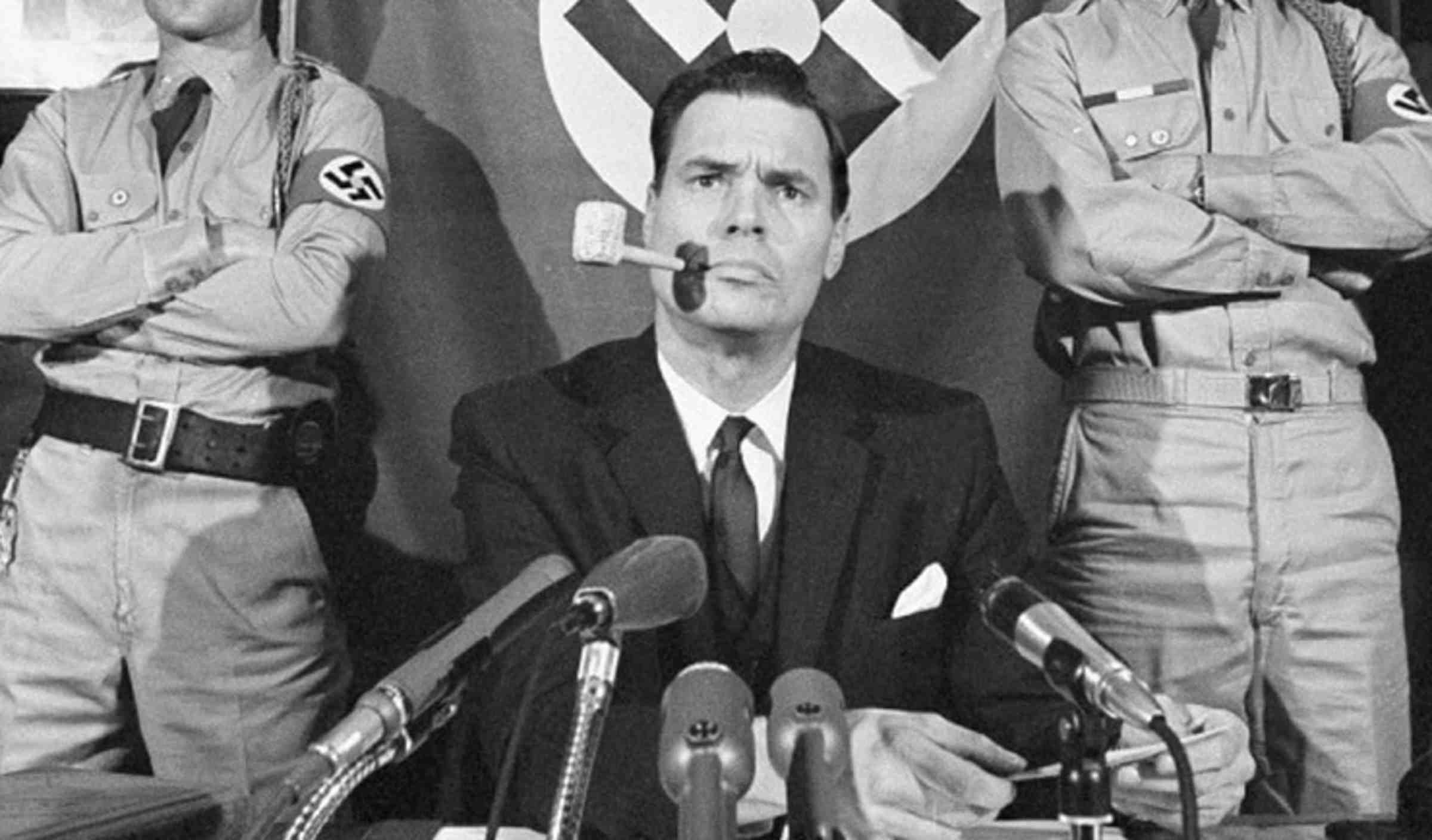

George Lincoln Rockwell, leader of the American Nazi Party, holds a news conference on November 3, 1965.

Harvey Georges/AP

Still, it was also obvious that the case would be controversial, so I immediately telephoned Illinois ACLU General Counsel Ed Rothschild to tell him that we were about to take the case. (Ed was a committed civil libertarian, a partner in a prominent Chicago law firm, and a respected leader on the Illinois ACLU’s board.) He listened quietly and, much to my surprise, said, “David, I order you to take this case.” Taken aback, I asked him why he was ordering me to do something so obviously within my authority to decide. Knowing I was Jewish, he responded, “David, I don’t think you fully understand how unpopular this case and your representation of the Nazis are going to be. Therefore I am ordering you to take the case so that when anyone comes after you, they will have to come after me, too.” His immediate and steadfast support was emblematic of the support of the entire ACLU throughout the case. His anticipation of the blowback against the ACLU’s involvement in the case proved to be prescient.

The preliminary injunction hearing started the next morning and lasted the entire day. The tense courtroom was packed with onlookers and press. Skokie’s corporation counsel Harvey Schwartz, one of the most honorable lawyers I had ever faced, and co-counsel Gilbert Gordon, an equally honorable lawyer, presented their case aggressively but fairly and without rancor. Skokie’s evidence came first. One of its star witnesses was Holocaust survivor and community leader Sol Goldstein, who testified that while a violent reaction against the Nazis was not planned, he was not sure he or other onlookers could restrain themselves from violence if the Nazis came to Skokie. Later in the hearing, Nazi leader Frank Collin responded with testimony that his organization was planning a peaceful assembly, that his followers would be in uniform and that they would carry signs and banners. There were to be no speeches and no weapons. At the end of the hearing, the judge issued a preliminary injunction against the Nazis holding an assembly in Skokie.

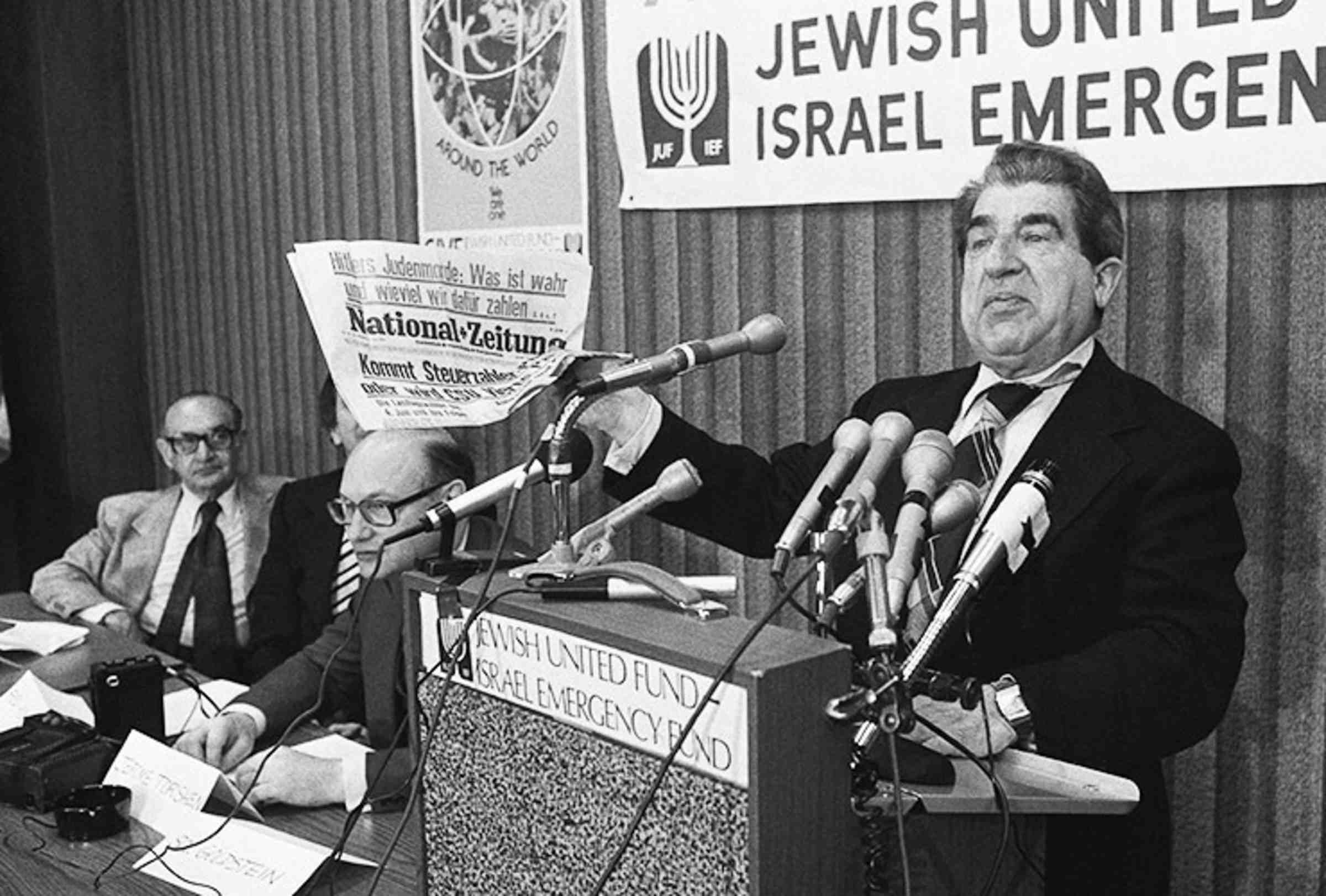

Sol Goldstein, spokesman for a group of Jewish organizations, holds up a German language newspaper with headlines questioning the validity of the Holocaust, at a news conference in Chicago, June 14, 1978.

AP

As soon as the injunction issued, we lawyers returned to the Illinois ACLU office to prepare an emergency appeal. Neither the state court of appeals nor the Illinois Supreme Court responded to our filings. The original date for the assembly passed, so we had no option other than to apply to the United States Supreme Court for an emergency order permitting the assembly to proceed as soon as possible after the original date. We argued that the Illinois courts’ delays in ruling amounted to a long-term prior restraint against speech — something that the Supreme Court had consistently rejected in cases like the Pentagon Papers case, where the Supreme Court overturned an injunction preventing the New York Times from publishing the Pentagon Papers, classified documents about the origins of America’s involvement in the Vietnam War.

The Supreme Court rarely granted emergency relief. However, in light of the pattern of delay by the Illinois courts, the court issued its decision within days, ordering the Illinois courts to decide promptly whether the injunction against the demonstration was constitutional. It further ordered that if the Illinois courts could not rule promptly, they had a duty to allow the demonstration. In short, the Illinois courts were ordered to quit stalling.

I initially thought the Supreme Court ruling would help everyone understand the importance of protecting First Amendment rights and that growing criticism would begin to die down. That was not to be. As days passed following the issuance of the injunction, the crescendo of criticism of our defense of the Nazis’ rights kept growing. The Chicago office was flooded with calls objecting to our efforts. Across the country, thousands of ACLU members resigned. (Some estimates were as high as 50,000.)

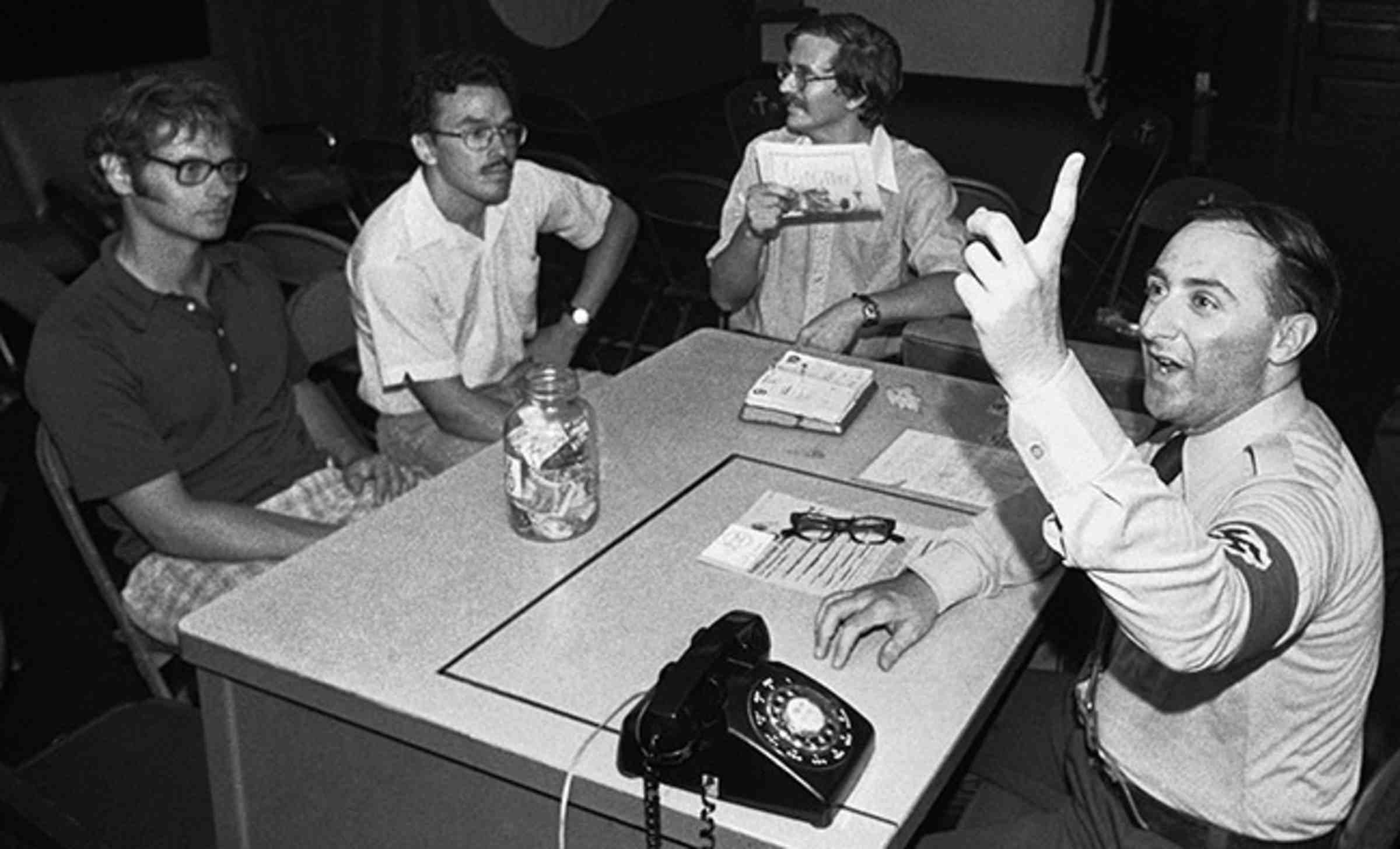

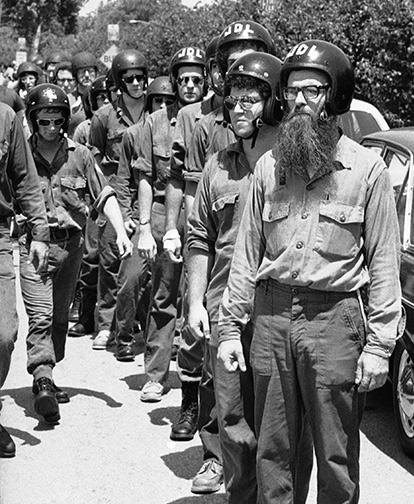

Clad in paramilitary gear and helmets, members of the Jewish Defense League arrive on Monday, July 5, 1977 in Chicago suburb of Skokie for an anti-Nazi demonstration.

AP

One night during the case, I received a call at home in which the caller said I would be punished for representing the Nazis. Late one afternoon, members of the Jewish Defense League appeared at the Illinois ACLU office reception area swinging baseball bats while a staff member hurriedly closed the door to my office so I would not be seen. At my parents’ synagogue, a rabbi gave a sermon excoriating me for defending the free speech rights of Nazis. Fortunately, my parents were not present at the time.

Still, the Illinois ACLU board responded by voting in support of our continued representation of the Nazis. The only dissent came from a longtime board member whose wife was a Holocaust survivor. He explained that he knew why the ACLU had to take the case, but that he could never personally vote to support such representation.

In spite of the Supreme Court’s ruling, the case dragged on for many more months. Afraid that its injunction against the Nazi demonstration would be overturned, Skokie passed a series of ordinances creating new obstacles. One required the Nazis to post an insurance bond of several hundred thousand dollars. Another prohibited members of political parties from participating in demonstrations while wearing military-style uniforms. We responded with a federal lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of the ordinances. Then, the Anti-Defamation League filed its own suit on behalf of Skokie’s Holocaust survivors seeking yet another injunction against any Nazi demonstration in Skokie. They alleged that if the Nazis came to Skokie, the survivors would suffer serious emotional harm by being forced to relive their personal Holocaust experiences. We responded that no one who objected the Nazis had to attend their demonstration and that if claims of subjective harm could shut down a public assembly than anyone who objected to a controversial demonstration could prevent it by asserting it would inflict emotional harm.

At the same time, a state legislator introduced a bill in the Illinois General Assembly seeking to criminalize the “public display of racial hatred.” The proposed law used language so sweeping that it would justify, for example, criminal prosecution of a Black Lives Matter leader for making a speech blaming white racism for police shootings of African Americans. Each of the lawsuits was fought to the bitter end, and one by one they ended in rulings that the Nazis had a First Amendment right to hold their assembly in front of the Skokie Village Hall. In the meantime, the proposed legislation was slogging its way through the legislative process.

Once the courts finally ruled in all of the cases that the Nazis had a right to peaceful assembly, it became clear that they were going to have their assembly. They announced that they would hold it in Skokie on June 24, 1978. From this point on, I repeatedly warned Frank Collin, the Nazi leader, that violent counterdemonstrations were planned — and that I doubted that the Skokie police and allied police departments were up to the job. Nonetheless, he told me that the demonstration was on and, as far as I could tell, his plans for it continued apace.

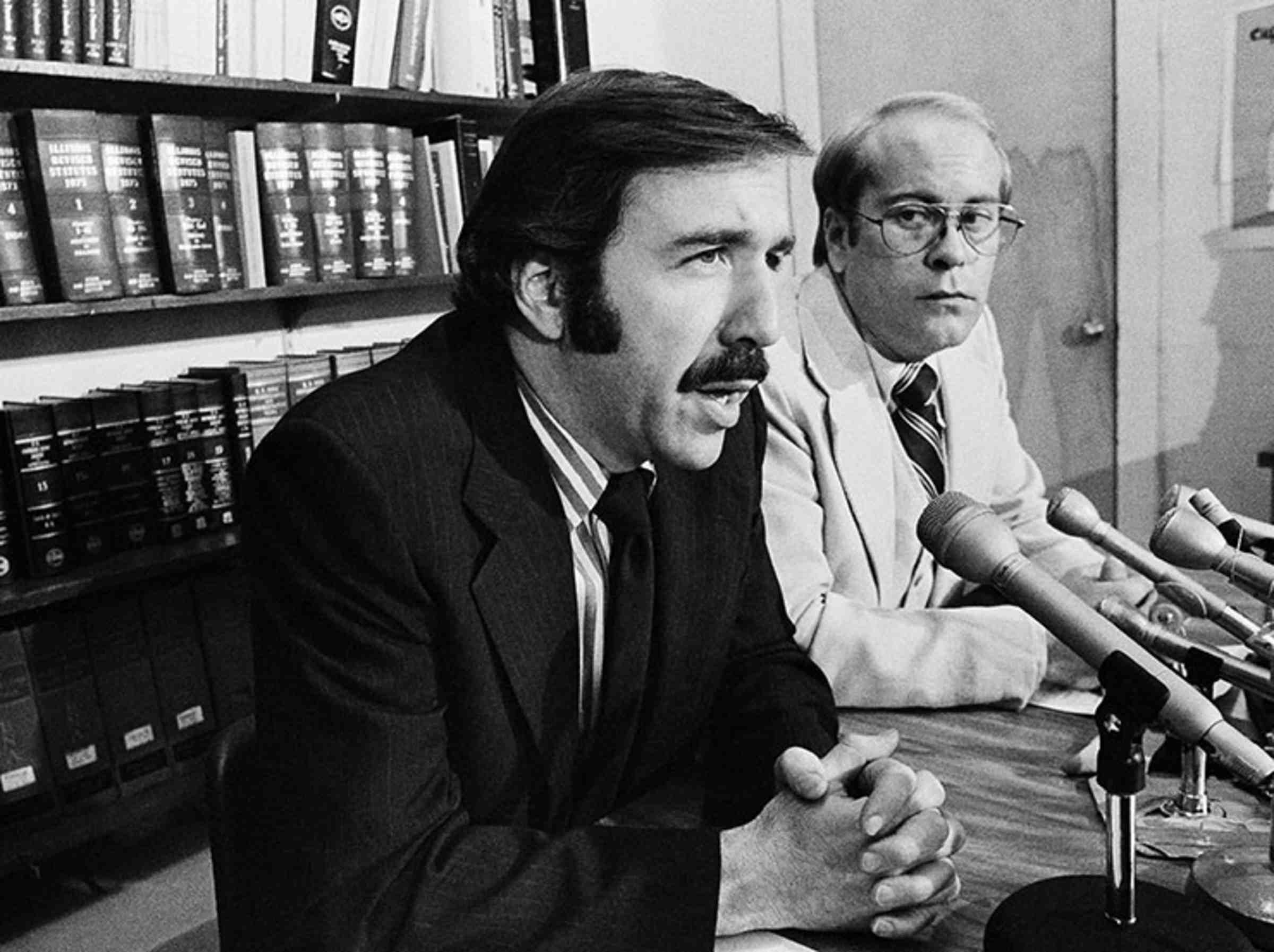

ACLU legal director David Goldberger, left, appears at a Chicago Press conference with ACLU Executive Director David M. Hamlin. Both men were happy with the court’s decision to allow Frank Collin and his Nazi group to hold a rally in Chicago’s Marquette Park.

AP

Then came a new development. Without my knowledge, Skokie officials had contacted the United States Justice Department in hopes that it could help them find a way out of the looming demonstration. As a consequence, about three weeks before the scheduled date for the demonstration, I received an unexpected call from the Justice Department’s Community Relations Service asking to meet with Collin. I relayed the request and Collin readily agreed.

At the meeting, Collin surprised everyone by changing course and telling the Justice Department representatives that he would agree to move the Skokie demonstration if three conditions were met. First, he wanted to hold the assembly in downtown Chicago. Second, he wanted to regain access to the Chicago park near his South Side headquarters. And, third, he wanted the speech-repressive legislation pending in the Illinois General Assembly to be stopped. Fortunately, the things Collin wanted were easily achievable. There was a large public forum next to the federal courthouse in downtown Chicago that required no permits. All Collin and his followers had to do was to show up. His two other demands were promptly accomplished by a successful motion in federal court granting him access to Chicago’s parks. And finally, presumably as a result of efforts by the Justice Department negotiators, the anti-hate speech bill failed to get enough votes for passage.

The Nazis’ demonstration was thus moved to downtown Chicago and, on June 24, with the assistance of an estimated 1,000 Chicago police officers to control angry counterdemonstrators, it went off without a hitch. Because tempers were running so high, I moved my family out of our house for the weekend of the demonstration. When we returned, I found that someone had thrown eggs at our front door.

Helmeted members of the Nazi Party of America salute during a rally in downtown Chicago, June 24, 1978. At center foreground in armband is the Nazi leader Frank Collin. The Nazis were pelted with eggs by anti-Nazi demonstrators.

AP Photo

To this day, the case still brings up difficult feelings about representing a client whose constitutional rights were being violated but who represented the hatred and bigotry that continues to erupt into America’s consciousness. I remember being attacked repeatedly as a traitorous Jew. And I remember the anxiety that I would be attacked physically. At one point I asked an off-duty Chicago police officer, who was a personal friend, to accompany me to a speaking engagement (in civilian clothes) where extremely hostile members of the audience were expected to be present. On another occasion, I asked a friend, a Vietnam War veteran of large physical stature, to accompany me on the theory that a hostile member of the audience would be less likely to act aggressively if I had the friend nearby. On two such occasions, hostile members of the audience were escorted to the door by local police.

Read the Entire ACLU 100 History Series

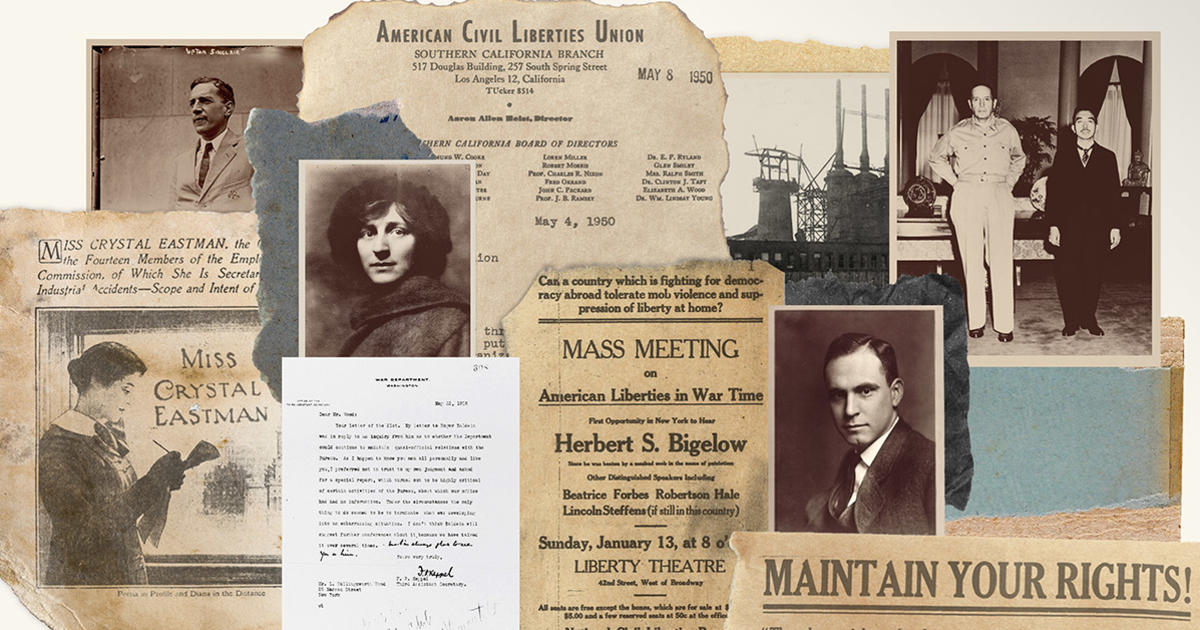

Source: American Civil Liberties Union

I also remember the impact of the case on ACLU membership. Resignations began to pour in from all over the country immediately after news coverage of the Supreme Court decision in the case. One Chicago-area member, a prominent rabbi, demanded that the Illinois ACLU Board hold a meeting open to all members so that the members could vote on whether the ACLU should continue to represent the Nazis. Although the affiliate had never before had a membership vote on ACLU involvement in a case, the Illinois board of directors held such a meeting in downtown Chicago to give ACLU members an opportunity to express their views. By a show of hands following heated statements pro and con, the vast majority of those members attending expressed support for ACLU’s work on the case.

Happily, much of the membership loss was offset by an ACLU fundraising letter to the membership that I drafted with the help of Ira Glasser, then the New York Civil Liberties Union executive director. That letter addressed the Village of Skokie’s ordinances that sought to prevent the Nazis’ demonstration. It explained that “...the Nazis are not the real issue. The Skokie laws are the real issue.” It pointed out that the ordinances were so broad that, “Skokie had already used the same law[s] to deny the Jewish War Veterans a permit to parade.”

I remember other instances of unexpected support, too. There were times when, during speeches I gave about the Skokie case, Holocaust survivors courageously stood up to say that I was right to have represented the Nazis. Several years later, another survivor sent me a letter saying the same thing. These survivors said that they did not want the Nazis driven underground by speech-repressive laws or court injunctions. They explained that they wanted to be able to see their enemies in plain sight so they would know who they were.

Their statements were like lights in the darkness of anger and misunderstanding. To this day, I have no doubt that the ACLU’s commitment to equal rights for all is a backbone of our democracy — no matter how offensive our clients are. Chipping away at this commitment will open the door to the erosion of the First Amendment as a bulwark against rule by tyrants.

A Postscript

After the Skokie case was over and I had left the ACLU staff to take a teaching position at the Ohio State College of Law, I learned that Skokie’s residents ultimately responded to the case by opening the spectacular Illinois Holocaust Museum. It honors the lives lost in the Holocaust. So, out of the pain and anger generated by the Skokie case arose the perfect answer to the Nazis — a monument to ensure that the damage done by the Holocaust will never be forgotten.

The Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center, Skokie, IL, seen here in 2009.

Eddau, Wikimedia

David Goldberger is the former legal and legislative director of the ACLU of Illinois. He was lead counsel in three U.S. Supreme Court cases, including National Socialist Party of America v. Village of Skokie. He is currently a Professor Emeritus at the Ohio State University Moritz College of Law, and is an expert on the Freedom of Assembly and the First Amendment.