Report Summary

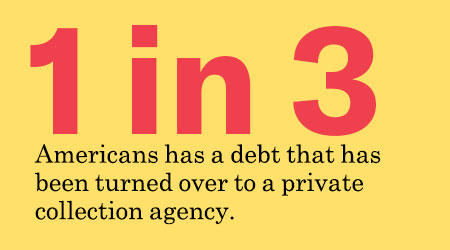

An estimated 77 million Americans have a debt that has been turned over to a private collection agency. Thousands of these debtors are arrested and jailed each year because they owe money. Millions more are threatened with jail. The debts owed can be as small as a few dollars, and they can involve every kind of consumer debt, from car payments to utility bills to student loans to medical fees. These trends devastate communities across the country as unmanageable debt and household financial crisis become ubiquitous, and they impact Black and Latino communities most harshly due to longstanding racial and ethnic gaps in poverty and wealth.

Debtors’ prisons were abolished by Congress in 1833 and are thought to be a relic of the Dickensian past. In reality, private debt collectors — empowered by the courts and prosecutors’ offices — are using the criminal justice system to punish debtors and terrorize them into paying, even when a debt is in dispute or when the debtor has no ability to pay.

The criminalization of private debt happens when judges, at the request of collection agencies, issue arrest warrants for people who failed to appear in court to deal with unpaid civil debt judgments. In many cases, the debtors were unaware they were sued or had not received notice to show up in court.

There are tens of thousands of these warrants issued annually, but the total number is unknown because states and local courts do not typically track these orders as a category of arrest warrants. In a review of court records, the ACLU examined more than 1,000 cases in which civil court judges issued arrest warrants for debtors, sometimes to collect amounts as small as $28. These cases took place in 26 states:

Contact Us

Do you have a warrant issued or threatened in a private debt collection case? If so please contact us at PrivateDebtReport@aclu.org.