From the Lunch Counter to the Supreme Court: Defending the First Amendment for All

As a young lawyer at the American Civil Liberties Union, I had the opportunity to show the impartiality of the First Amendment by representing plaintiffs whose outspoken views on racism made them my polar opposites. In this case, I was defending the First Amendment as much as the individual parties I represented. In our country, where the right to speak means the most to people like me, an African American woman, who are not automatically part of the larger majority, the First Amendment serves an outsized purpose.

Before I joined the ACLU to defend the First Amendment rights of others, I was a citizen who made full use of my free speech rights. It did not take much for a girl growing up in the nation’s segregated capital to become an activist. That activism, which sent me to Mississippi with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in 1963, was made possible by the First Amendment. Growing up in the District of Columbia was ample preparation for the civil rights movement, not only because of racial segregation in the nation’s capital, but also considering that D.C. was directly controlled by the federal government until the 1973 Home Rule Act and had no mayor or city council, and no Member of Congress. Deprived of the basics of democracy, compelled to abide by racial segregation, and denied representation in Congress, my hometown prepared me to look to the First Amendment for change.

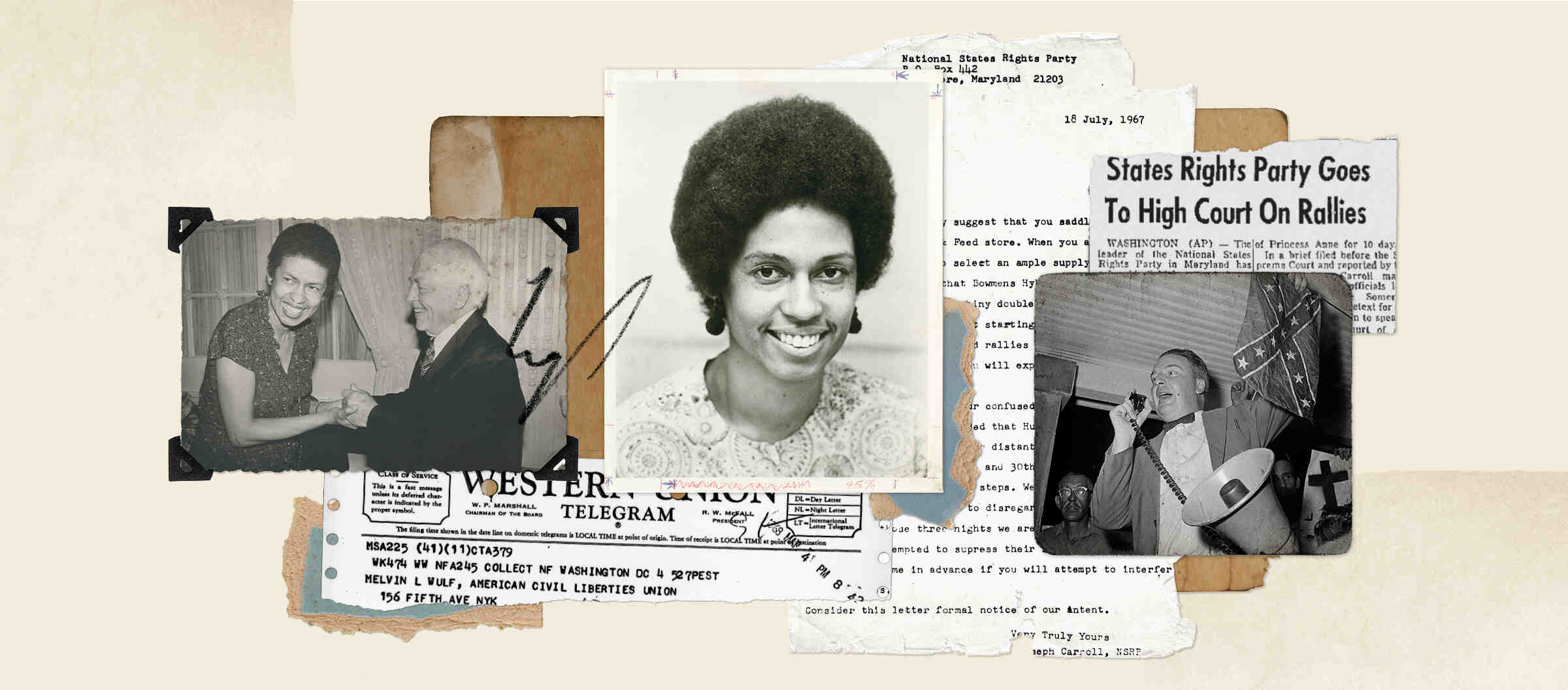

Portrait of the author as a young woman.

Police were more used to unruly crowds than demonstrators conducting sit-ins or peacefully picketing and occupying white-only spaces. Although nonviolent, many of our actions were illegal. Yet police had no training for handling such tactics. Eventually, though, billy clubs and arrests met their match as public opinion grew to favor the civil rights activists, who used the First Amendment. In turn, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which barred discrimination in public and private accommodations; it also provided a remedy for discrimination in employment and mandated an agency to enforce the new rights, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. (Perhaps needless to say, I could not have imagined that I would one day be appointed by President Carter to head the EEOC.)

The revolution in basic rights that the civil rights movement achieved depended on First Amendment protected speech and action by people of every race and background who pushed the amendment to its limits. We had no power except for the power guaranteed us by the right to speak and to protest.

Except for our audacity, SNCC’s insistence on directly confronting segregation was not that different from the marches and demonstrations led by Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. But as activists, we did not litigate for our rights. Our weapon was the First Amendment. We demanded our rights in the streets, at lunch counters, and at other public places in nonviolent confrontations wherever power could be challenged. Power presented itself as outright racial segregation in the South, and as unavoidable racial discrimination in the North. Our most effective ammunition were demonstrations and other forms of activism. We were beholden to the First Amendment to make our case.

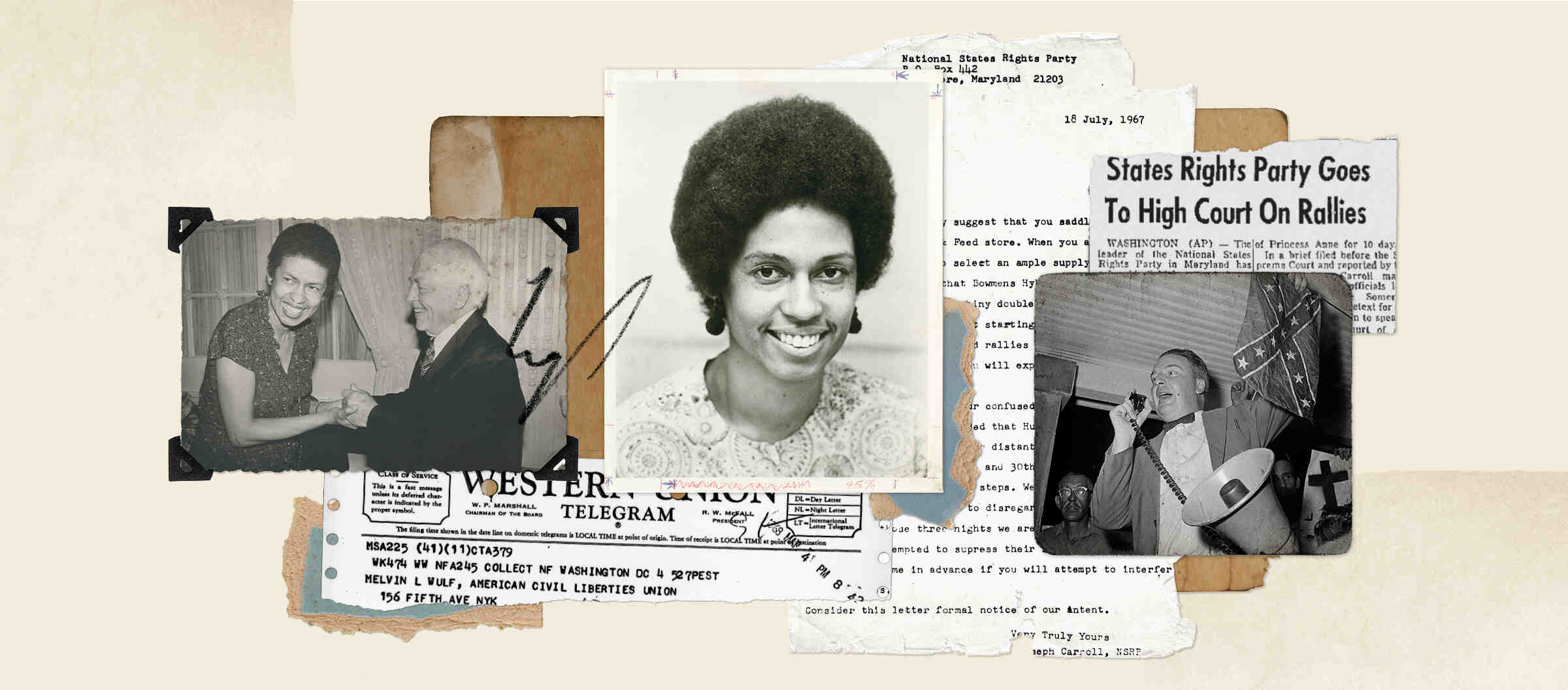

Undated photograph of Chief Justice of the United States Earl Warren.

Harris & Ewing Photography Firm/Wikipedia

The fruits of the movement’s First Amendment action also led to two more landmark civil rights laws. The 1965 Voting Rights Act assured the right to vote in Southern states, where the vote had been all but denied for a century, and the 1968 Fair Housing Act barred discrimination in housing, one of the most tenacious forms of racial bias.

However, the 1960s was not only the decade of the civil rights movement. These were also historic years for the Warren Court, when the court broke with prior decades and issued some of its great civil liberties decisions. Besides the most groundbreaking, ending racial segregation in public schools (the District was among the plaintiffs), the Warren Court issued opinions ensuring equal representation in state legislatures, expanding constitutional rights for defendants, and opening the path for legalization of abortion, among many other historic decisions.

It was my good fortune to work for the national ACLU, fresh out of law school, where I helped bring a case that became one of the Warren court’s landmark civil liberties decisions. That case was Carroll v. Town of Princess Anne, a monumental First Amendment decision that appeared in both the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals and in the U.S. Supreme Court. Along with the cooperating attorney, William Zimmerman, I presented the constitutional arguments in both courts.

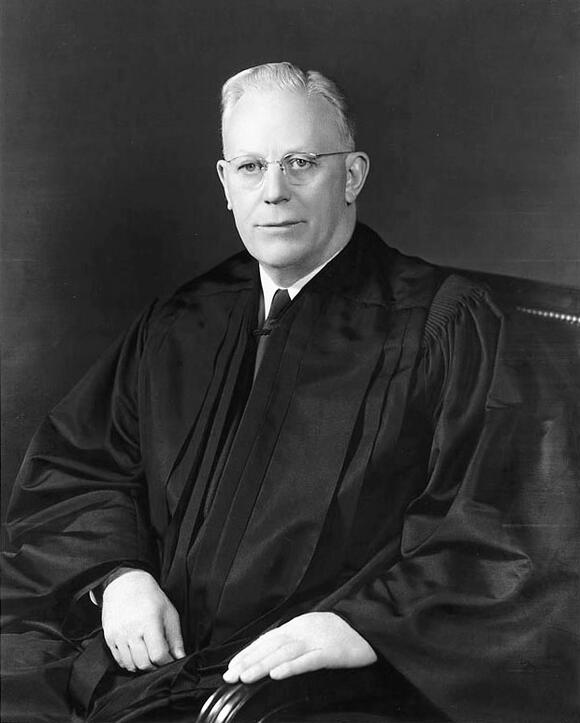

Our client, members of the National States’ Rights Party (NSRP), called themselves a white supremacist organization. According to the Supreme Court, the group held “an aggressively and militantly racist” rally in a small Maryland town with a crowd of 150 people, some of whom were Black. After the rally, with 60 police held close on standby, party members announced they would return for another rally the next night. Maryland county lawyers rushed to obtain a court order that barred the NSRP from holding a rally for 10 days, which was later extended to a 10-month injunction prohibiting the rally.

J.B. Stoner, a segregationist from Atlanta and attorney for the National States Rights Party, holds a confederate flag as he addresses a large crowd of white people in St. Augustine, Florida, on June 13, 1964. He then lead them on a long march through the city's African American residential section. At right is sign that reads “Kill Civil Rights Bill.”

AP Photo

The NSRP surely did not envision that one of their lawyers would be a young Black woman. Still, some of them came to the 4th Circuit and approached me with praise following oral argument. Although the 4th Circuit overturned the 10-month injunction against NSRP’s rally, the court allowed the 10-day injunction to stand. We appealed to the Supreme Court.

At 31, I barely met the three years of required practice for membership in the Supreme Court bar. Although I was not unpracticed in public speaking, I tried to overcome my legal inexperience with ample preparation. Yet preparation was not all I had to think about. Counsel before the Supreme Court generally were not young, female, or Black, much less with an afro (well before Black women wearing their hair natural was routine). I decided to be myself, not a female version of a Supreme Court counsel in a black suit. I wore a blue dress with a high collar but short sleeves, whose fashionably short length, just above the knees, was in keeping with the style of the day.

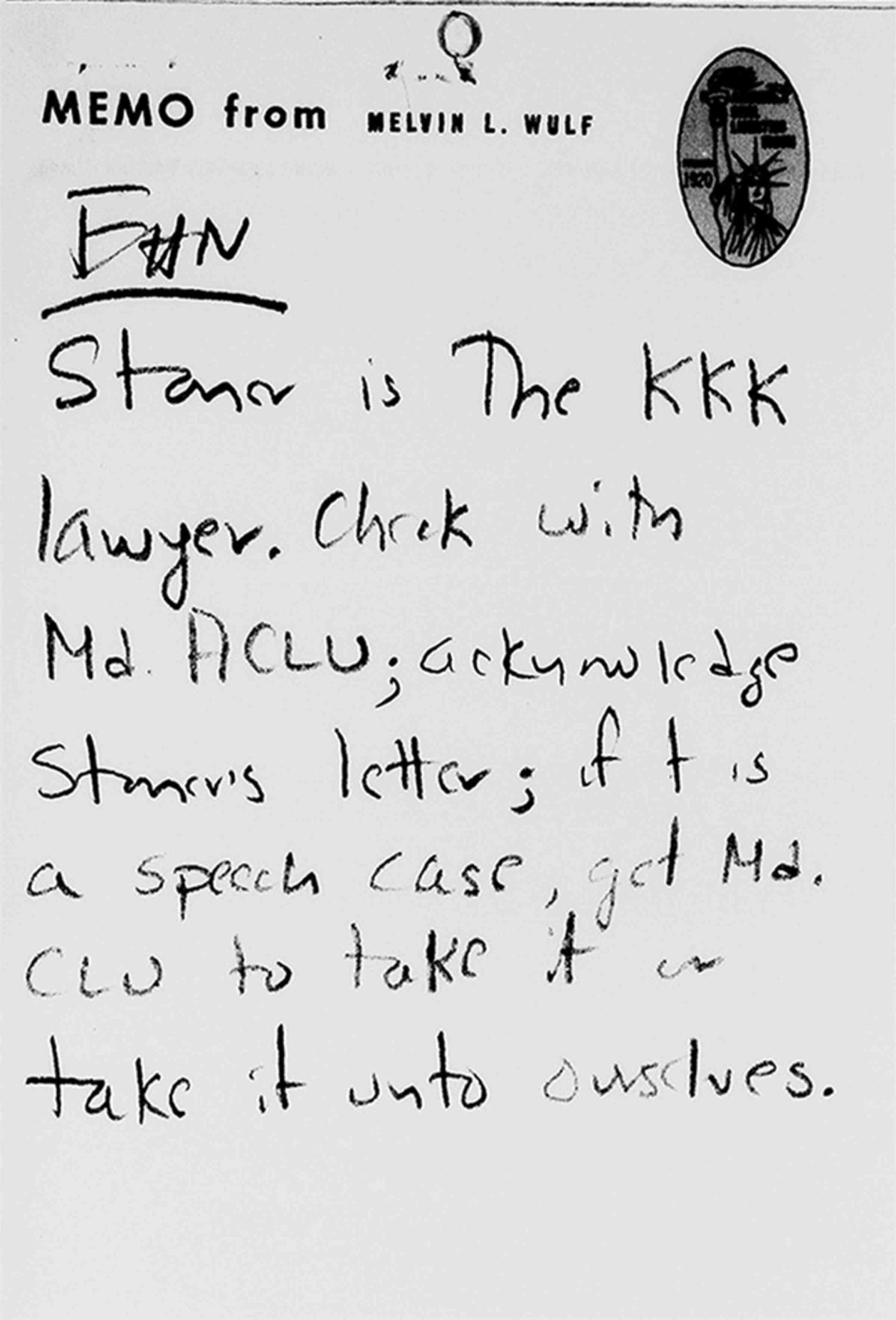

Memo from notepad of Melvin L. Wulf (ACLU) to Eleanor Holmes Norton, giving instructions regarding handling of a letter from attorney (Stoner) suggesting ACLU take case, October 15, 1968. The text reads "EHN - Stoner is the KKK lawyer, check with MD ACLU; acknowledge Stoner's letter; if it is a speech case, get MD CLU to take it or take it unto ourselves."

Princeton University

What confidence I summoned before the court came in no small part from my intellectual and visceral antagonism toward attempts to keep people from speaking, known in the law as prior restraint. Gains in the civil rights movement would have been impossible if activists had been shut down before they could speak. Meeting resistance from those opposed to our words or protections was not unusual. But being illegally barred from speaking at all was unthinkable.

The Supreme Court affirmed the continued importance of the First Amendment by refusing to find the case moot, although the 10-day injunction approved by the 4th Circuit had long expired. The Maryland Court’s decision granting the 10-day injunction had allowed the NSRP to hold rallies so long as they no longer exercised their First Amendment rights to use racially divisive language. The court observed that the NSRP continued to hold rallies after the injunction had expired, and the injunction continued to limit the right of NSRP members to express their views.

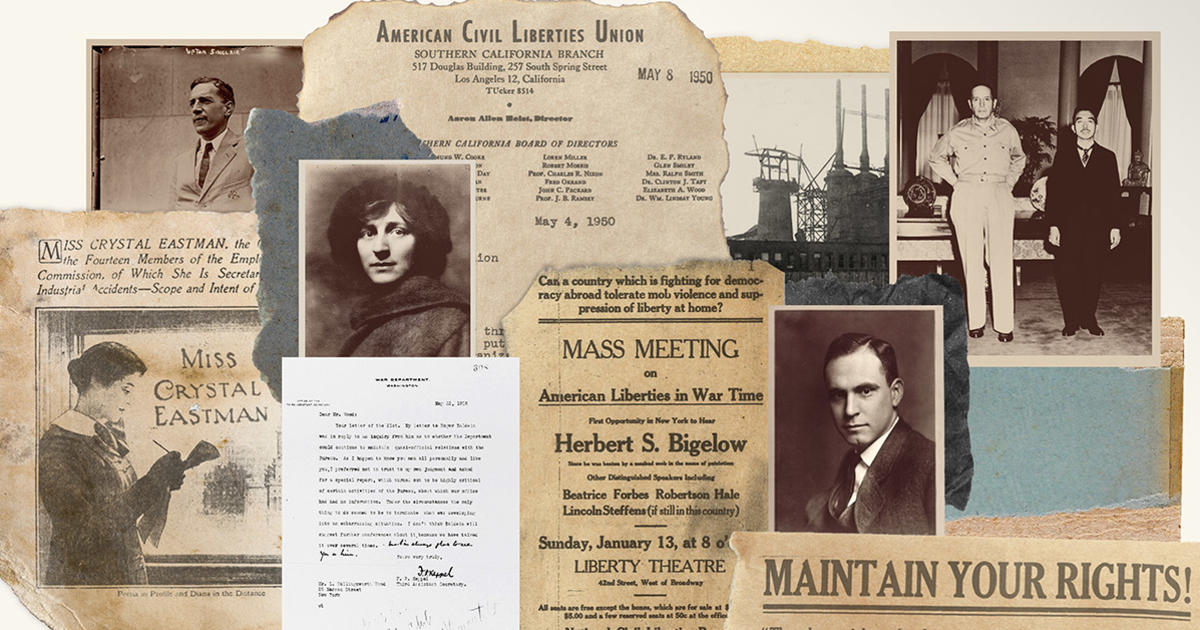

Read the Entire ACLU 100 History Series

Source: American Civil Liberties Union

Most importantly, the issuance of an injunction without the opportunity to be heard, the court said, was unconstitutional prior restraint on speech. For such an injunction to survive “within the area of basic freedoms guaranteed by the First Amendment,” restraining orders must be short in duration, and it must be possible for those wishing to speak to challenge them. The Maryland court had therefore created a standard for those wishing to speak that was virtually impossible to be overcome.

Notwithstanding the procedural flaw in issuing the injunction, the Supreme Court was clear on the principle of the Carroll case: “Prior restraint upon speech suppresses the precise freedom which the First Amendment sought to protect against abridgement.” The court did not allow the procedural issue in the case to obscure the overriding necessity to avoid “the dangers of a censorship system.”

The effects of Carroll continue to this day. In the years since, the case has deterred federal and state governments from even attempting to limit speech before it occurs. Carroll has set the bar so high that the government has never won a prior restraint case in the Supreme Court since. I can only hope that what I do in Congress will have as lasting an effect as Carroll v. Town of Princess Anne has had on the First Amendment.

Congresswoman Norton in 2006.

Wikipedia

Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton is a civil rights and feminist leader, a former professor of law at Georgetown University, and represents the District of Columbia in the U.S. House of Representatives. Before serving in Congress, President Jimmy Carter appointed Norton to serve as the first woman to chair the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and two New York City mayors appointed her as the first woman to chair the city’s Human Rights Commission. Her work as a civil rights activist began as a student with SNCC in Mississippi and on the staff of the March on Washington. Her work for D.C. statehood today continues her lifelong struggle for civil rights. Norton currently serves as the Chair of the House Subcommittee on Highways and Transit, as well as a top Democrat on the House Committee on Oversight and Reform. Her work in economic development has transformed entire neighborhoods in the District and she has spent her career as a lawyer representing African Americans and women who broke barriers.