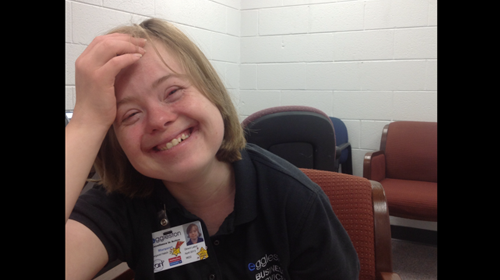

The guardianship system in this country raises serious concerns. That's why the guardianship trial of Jenny Hatch, a vibrant and active 29-year-old in a battle over who controls her life, struck such a chord. Jenny spoke for many other people with disabilities when she said clearly in her trial: "I don't need guardianship. I don't want it."

On Friday a judge in Virginia denied guardianship to the parents of Jenny Hatch. Hatch will instead be able to live with her friends, couple Kelly Morris and Jim Talbert, as she had requested. This is a victory, but it should never have come to this.

If anyone else had been placed in an isolated location, against her will, with her cell phone and computer taken away, and not allowed to leave the building without permission, as Hatch was, she would either be able to lodge a charge of kidnapping, or be a prisoner convicted of a crime.

But, because Hatch is a person with a disability – and only because of that – it is completely legal, even though she has done nothing wrong.

Guardianship can, and often does, deprive a person of the ability to choose where she lives, who she sees, when she gets up in the morning, what she eats for breakfast, whether and where she works and whether she is allowed the right to vote.

Guardianship is typically created under two circumstances:

- When adults – often seniors – develop a disability, especially one that affects the ability to manage finances or make complex decisions, their spouse or child is often encouraged to become their guardian.

- And, when a child with developmental disabilities reaches 18, her parents are often encouraged to become the child's guardian – ostensibly so that they can continue to participate in medical and educational decisions for the child.

In both circumstances, other less restrictive options are available.

In the U.S., creating a power of attorney for health care or a power of attorney for financial matters is a better solution much of the time. These are contracts between the person with a disability and someone they trust – and choose themselves – to help advise them, or to make decisions if they are unable to. The person with a disability still keeps the right to make decisions in other areas of his or her life.

In another model, known as "supported decision-making," the person with a disability chooses a team of people to help her with decisions, and who have signed up to be available for advice and assistance. In Hatch's case, the judge was persuaded that this was the model to move toward. He recognized that Hatch should be able to choose who she lives with, who should advise her, and what she does with her life – but, like all of us, she would benefit from a support system to help with major decisions. Talbert and Morris will have guardianship of Hatch for one year – after which they will move to the supported decision-making model.

Supported decision making and providing powers of attorney are the options we should look to first – rather than reflexively choosing guardianship and stripping a person of every civil liberty.

We still know too little about the full picture of guardianship in the U.S. We don't know how many people are under guardianship, much less the distribution between younger people with disabilities and seniors. Most importantly, we don't know how many guardians are respectful of their wards' wishes, and how many are callous, or downright abusive. What we do know is that it is the most draconian deprivation of an individual's rights in civil society.

So, what should we do?

We should have more, and clearer, conversations about guardianship that include the voices of those who are most affected by guardianship's grasp. We need to explore and further develop the best models to support individuals with disabilities in their decision-making. And, we need to be cautious when anyone suggests guardianship for our children, our parents or ourselves.

Most of all, we must recognize that disability should not be an excuse to deprive someone of her basic civil liberties.

Learn more about disability rights and other civil liberties issues: Sign up for breaking news alerts,follow us on Twitter, and like us on Facebook.