Can We Fire the Electoral College? Probably Not, but We Can Put It Under New Management

This piece originally appeared at The Huffington Post.

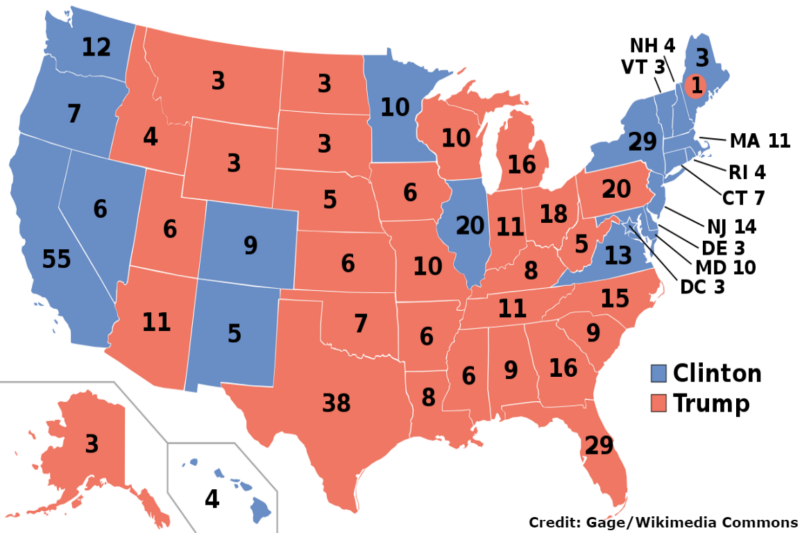

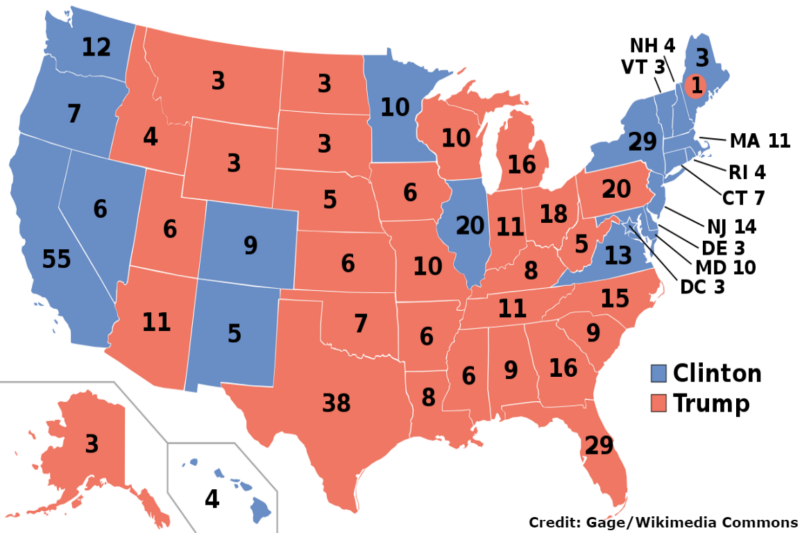

The electors of the Electoral College met this afternoon in their respective states and anointed as president the candidate who won the popular vote in a larger number of states — Donald Trump — regardless of the fact that another candidate — Hillary Clinton — won the larger number of votes by several million.

The ACLU has opposed the Electoral College since 1969 for non-partisan reasons. By now — everyone, Republicans, Democrats, and none-of-the-aboves — should be fed up with its undemocratic and unpredictable nature.

Unfortunately, amending the Constitution to eliminate this atavistic system is a practical impossibility for the same reason the Electoral College is a problem: The less populous states have a disproportionate share of voting power. Constitutional amendments require approval by three-quarters of the states, not a national majority or even super-majority of voters. Most states are currently Republican-dominated, and Republicans may believe at the moment that the peculiarities of the Electoral College will help to serve their partisan goals in future elections.

That may not be true. The Democratic candidate did win the popular vote in this election. But in 2004, if John Kerry had won Florida or Ohio he would have passed the winning threshold of 270 Electoral College votes even though George W. Bush won the popular vote by several million votes.

More importantly, after an uncommonly brutal election season, we need to start rising above result-oriented partisanship and focus on whether our system for selecting a president is consistent with our fundamental principles.

The Electoral College Has a Sorry History

Alexander Hamilton, the current darling of Broadway, promoted the Electoral College in

“Federalist 68” for deeply elitist reasons — he did not trust the common people to select the president. Notes of the Constitutional Convention show that the Electoral College’s unequal distribution of voting power was chosen as part of a sordid bargain: Along with the 3/5 Clause, the Electoral College was part of a compromise over slavery. States like Virginia wanted political influence commensurate with their total population even though they did not allow a large percentage of their population — slaves — to vote.

This historical artifact should have gone the way of the 3/5 Clause. Even if, like Hamilton, we wanted an oligarchy to choose our president, today’s Electoral College is not a deliberative body. Although the Constitution does not require either of these approaches, most states have chosen to adopt laws requiring electors to cast their votes for whoever wins the state’s popular vote; 48 states decided on a winner take all system. Whether an elector is permitted to exercise any independent judgment at all is hotly debated.

The Electoral College thwarts the fundamental principle of one person, one vote by awarding each state a number of electoral votes equal to its allocation of representatives plus its two senators. A voter in Wyoming thus has over three times as much influence on the presidential election as a voter in more densely populated California. And there are still racial and ethnic disparities in voting power. One recent study calculated that Asian-Americans have barely more than half the voting power of white Americans because they tend to live in “safe” states — like Democratic-leaning New York and California and Republican-leaning Texas.

Furthermore, the number of representatives each state receives, the baseline for Electoral College representation, is determined by the census. But the census consistently undercounts minorities. The Census Bureau itself calculated that the 2010 census missed 1.5 million minorities, including 2.1 percent of African-Americans and 1.5 percent of Hispanics. The marginalization of minority voters in many states is compounded by state voter suppression laws.

The smaller states argue that they will be ignored if they do not have more than their proportionate share of voting power. But the Electoral College system makes wallflowers of most states, including the most populous, and therefore of most of the American people. Two-thirds of 2016 presidential election events took place in half a dozen swing states. Less populous states already get to put several fingers on the scales in the Senate and in the constitutional amendments process. Why give them another undue advantage when our government is supposed to be run by “we, the people,” not “we, the states”?

The National Popular Vote Act Solution

Even without a constitutional amendment, the states have the power to fix the main problem of the Electoral College. If enough states enact the National Popular Vote Act (NPVA), the winner of the national popular vote would become the winner of the presidential election.

Under the NPVA plan, states enact a law requiring their electors to vote for the winner of the national popular vote (rather than the state’s own popular vote). The act becomes effective only after states with electoral votes totaling at least 270 have passed the legislation. Eleven states (CA, D.C., HI, IL, MA, MD, NJ, NY, RI, VT, WA) with a total of 165 electoral votes have already passed the NPVA. If states with electoral votes totaling 105 more votes pass the act, the winner of the next presidential election will be selected by popular choice.

This state-based approach is consistent with the framers’ decision in Article II to authorize the states to control the appointment of electors. If it is constitutionally permissible for states to instruct their electors to vote for the winner of the state’s popular vote (the prevailing practice today), the states must also have the power to choose a different benchmark.

Dozens of pro and con arguments — more than can be explored here — have been made about the constitutionality of the NPVA approach. It is probably true that the Electoral College cannot be wholly eliminated without a constitutional amendment. The NPVA would not eliminate the Electoral College but simply place it under new management — the American people’s. The ACLU supports the NPVA because we believe that the responses to the range of opposing arguments are more persuasive.

Although the states adopting the NPVA so far tend to be blue states, the movement has been bipartisan — as it should be. In February, the Arizona House became the third majority-Republican state legislative chamber to approve the act (following the New York and Oklahoma Senates) in a bipartisan 40-16 vote. If state legislatures refuse to go along, voters should take matters into their own hands with ballot initiatives to require that their states adopt the NPVA.

The Electoral College has been a predictable rubber stamp so far, but there is always the chance of a December surprise from so-called “faithless electors” who don’t vote as expected. Why should we tolerate this degree of unpredictability from a group we don’t actually want or expect to be exercising their own judgment? Even if we can’t agree on results, we should all be ready to agree on principle that our president should be chosen, like all of our other elected officials, by the straightforward popular vote.