I Was a Muslim Teen Under NYPD Surveillance. But Now I Have More Hope Than Ever.

When I was 20 years old, I sued the largest police force in the country over its blanket surveillance of countless New York Muslims — me among them.

The decision to join the lawsuit was a difficult one, to say the least. I was terrified that going public about my experience would open me up to suspicion and backlash from my community and beyond, and that my budding academic and professional career could be damaged forever.

My fears were proven wrong. Our lawsuit against the NYPD has led to a strong settlement proposal, and my community is readier than ever for the mounting challenges facing American Muslims today.

It started when I was a 19-year-old community college student in Brooklyn. I received a Facebook message from a young man who said he wanted to become a better Muslim. He contacted me because he knew I was volunteering in a community-based charity that was aiding low-income families and the homeless.

We had some Facebook friends in common, so I introduced him to a few of my friends at the charity. Immediately, he began getting involved with our organization. He met many of my friends and came to my family’s home, even spending the night once.

My new friend was anything but. After a few months, he publicly revealed himself as an NYPD informant. I was stunned and terrified. I was born and raised in Brooklyn and I hadn’t done anything wrong. Yet my charity — and my family —had been infiltrated by one of the most powerful police forces in the country, if not the world.

As I would later find out, my “friend” the informant was part of a broad NYPD effort to penetrate the most intimate facets of Muslim life in New York City. Plainclothes officers fanned across the city to map Muslim “hot spots,” collecting information on mosques, charities, and innocent conversations in popular cafes. Informants infiltrated mosques, feeding photographs and names of congregants into police databases. An entire religion was viewed as suspicious.

My charity barely survived the damage the informant caused. Members and volunteers retreated out of fear. We were asked not to hold meetings at the mosque that had previously hosted us. Our ability to fundraise was significantly hampered.

The damage to my organization, however, was the tip of the iceberg. When we learned from the Associated Press about the full extent of the NYPD’s infiltration of New York Muslim life, it was like an earthquake had struck and our communities’ worst fears were confirmed. Mosques became even more anxious that newcomers were sent by the police. A chill swept through cafes and other businesses. Nobody knew whom to trust and people grew more afraid to voice their views openly. The world felt like it was closing in on us — because it was.

I felt powerless. I needed to push back. In 2013, I joined five other plaintiffs — three religious and community leaders and two mosques — to sue the NYPD. This week, we announced a settlement with the police department that will prevent a repeat of what we lived through. If the settlement is approved, the NYPD won’t be able to launch investigations based on discriminatory premises. They will also limit the use of informants and will be checked by a civilian representative with extensive authority to monitor the department’s compliance and to report violations. (Click here for more details on the terms of the settlement.)

This settlement is even better than an earlier version we announced last year, thanks to a federal judge who ordered it to be strengthened. Given that many of us had assumed we wouldn’t find justice in the courts, I can’t overstate how encouraging it was to hear Judge Charles S. Haight, Jr. express the need to protect all New Yorkers from discriminatory policing.

Yet even as we taste victory in our struggle to reform the NYPD, a bigger fight is only beginning. The 2016 election season left my community stunned and fearful of the rising anti-Muslim sentiment across this country. Many relatives and friends are worried about the many ways we might be stigmatized because of our faith.

My mother wants to visit family in Pakistan this year, yet I’m afraid of what she might face at the airport. A Syrian asylum seeker friend doesn’t know what her future holds. Iranian friends worry they won’t see their family members again. I, too, am scared to travel internationally — could I one day be refused reentry into the country of my birth?

These fears can be gripping. But they are also steadily countered by hope, in no small part thanks to the support of allies nationwide. I’ve received more messages than I can count from non-Muslim friends and peers asking what they can do to help. They want to know which Muslim civil rights groups they should donate to, whether I have friends who needed protection, what kinds of books about Islam I recommend. American Muslims are not alone in rejecting hate.

My personal resistance started in 2013, but in many ways, it feels like it’s just beginning. Last week, I was accepted into New York University’s M.A. program for Near Eastern Studies. I hope to produce research on human rights and social justice through the prism of Islam, to help people understand the goodness that is inherent in my faith. I also hope to spend the summer in an intensive Hebrew-language program at Middlebury College, which will enrich my own appreciation of Semitic languages and history while building bridges to the Jewish community.

On January 13, one week before inauguration, I gave a Friday sermon at the Islamic Center at NYU. Standing before hundreds of people, I reminded my community of the importance of hope and the need for resilience, and I asked people to be ready to put themselves on the line to protect and amplify the voices of the city’s most vulnerable residents. The despondency that felt palpable at the start of my sermon gave way to a renewed sense of confidence.

We know as well as anyone that resisting discrimination does more than just achieve a narrow goal — it also brings communities together and demonstrates what’s possible. Our successful struggle for the right to practice our faith proves to me that we’ll be able to face whatever comes our way.

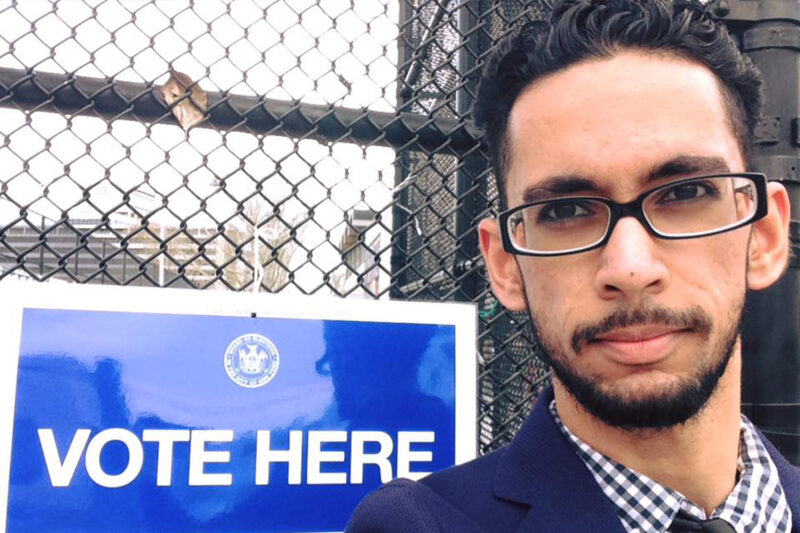

Asad Dandia graduated New York University with a Bachelor's in Social Work with a focus on community organizing. He hopes to continue advocating for marginalized communities as he pursues a Master's in Near Eastern Studies this fall at NYU.