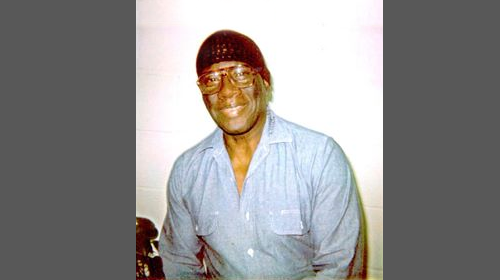

Herman Wallace died this morning. He was 71 years old and debilitated by terminal liver cancer. Three days ago, he went home to New Orleans for the first time since he was a young man. He has spent virtually all of the last 42 years locked alone in a room the size of a parking space.

This elderly and terminally ill man was in solitary confinement just a few days ago. He was one of tens of thousands of people in isolated confinement in this country every day.

Who are the others? Thousands of them are non-violent. Many are mentally ill people who were sent to solitary confinement—and remain there—as punishment for behavior connected to untreated psychiatric conditions. Some are teenagers incarcerated in the adult system and transgender women in male facilities, who are all too often placed in isolation "for their own protection."

It's a myth that solitary confinement is only used on a small subset of prisoners deemed "the worst of the worst;" sadly, it's far more common than that.

After 42 years, it's wonderful that Mr. Wallace died a free man. It's important to tell his story, both because of the injustices that led to his solitary confinement and because it is a reminder of the thousands of others who continue to be subjected to extreme isolation in our jails and prisons.

In 1974, Mr. Wallace was convicted of the murder of a corrections officer at Louisiana's Angola prison, where he was serving a sentence on other charges. Mr. Wallace's conviction was based on sparse evidence and a shoddy investigation; he was also indicted by a grand jury from which women were unconstitutionally excluded. Moreover, it is widely believed that racism and retaliation (Mr. Wallace was a vocal member of the Black Panther Party) were factors in his prosecution. It took until Tuesday, but Mr. Wallace was finally released from prison after a court order overturned his conviction.

Mr. Wallace and two other men placed in decades-long solitary confinement at Angola became known as the "Angola 3," and their story has been told all around the world. While one of the men, Robert King, was released in 2001, the third, Albert Woodfox, remains in solitary confinement. On Tuesday, Wallace's legal team said that Mr. Wallace hopes that his case "will help ensure that others, including his lifelong friend and fellow ‘Angola 3' member Albert Woodfox, do not continue to suffer such cruel and unusual confinement even after Mr. Wallace is gone." Robert King also recently expressed hope that the story of the Angola 3 would help bring about change in an unjust system.

The order overturning Mr. Wallace's conviction and directing his release is no doubt a victory, but it is a bittersweet one. Mr. Wallace's release, after so many years and coming just days before his death, highlights the cruelty of solitary confinement. The practice, which involves holding prisoners in tiny cells for 22 to 24 hours a day, is widely used in American prisons. The experience of prolonged isolation can lead to extreme psychological harms including severe and chronic depression, hallucinations, self‐mutilation, and suicide. Nobody deserves such treatment, which the international human rights community has denounced as torture.

While there is still a long way to go, some initial steps have recently been taken to put an end to this inhumane treatment. The Federal Bureau of Prisons will soon undergo a comprehensive and independent review of its use of solitary confinement. And new regulations under the Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) impose important limitations on the use of "protective" isolation, recognizing the particular vulnerabilities of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex (LGBTI) individuals, youth, and people with mental illness to prolonged isolation, and include mechanisms to restrict the practice of warehousing prisoners in segregation with little oversight.

Herman Wallace waited 42 years only to be released from solitary confinement on his deathbed. After his death, our hope is that Mr. Wallace did not struggle in vain, and that his story will prevent others from enduring the sensory and social isolation that he lived through for more than two decades.

Learn more about solitary confinement and other civil liberty issues: Sign up for breaking news alerts, follow us on Twitter, and like us on Facebook.