Nebraska Legislature Overrides Governor's Veto and Gives Dreamers Their License to Drive

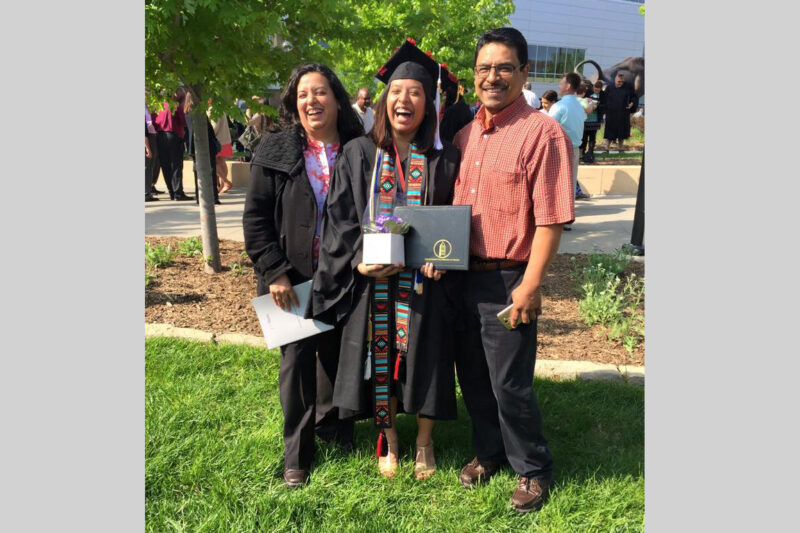

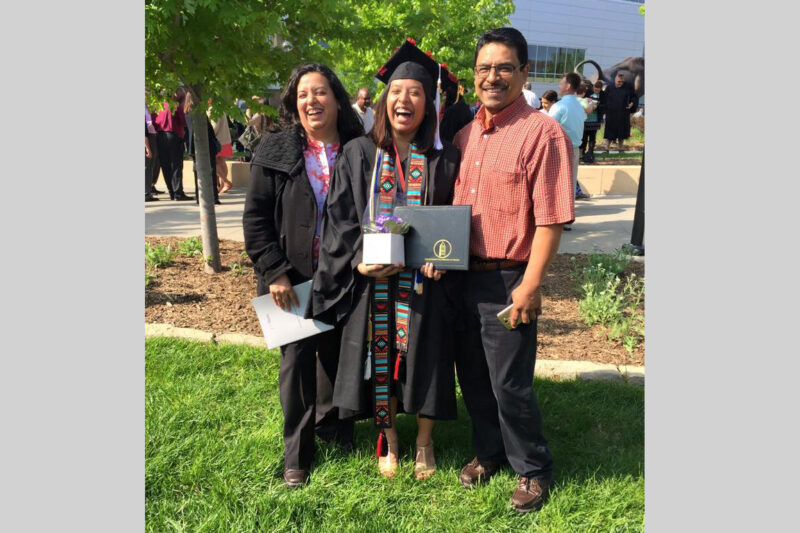

Maria Marquez Hernandez just graduated from the University of Nebraska at Omaha with a degree in psychology, but she still can't give her younger sister a ride. That's because she's a Dreamer — brought to the U.S. by her parents and raised undocumented as a child.

Shortly after the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program was announced in 2012, Maria applied for DACA and received a Social Security number and work authorization card, which ordinarily would have allowed her to apply for a Nebraska driver's license. But the former and current governor decreed that Dreamers could not qualify for driver's licenses, even if they presented that documentation. This has made daily life difficult for Maria, but not being able to do what other big sisters do bothered her most.

Buckle up. This week that changed when the Nebraska Senate voted in dramatic fashion to let Dreamers drive.

Maria loves Nebraska, which she has called home since the age of five. But as she has noted, standing up for herself and others in the face of injustice is part of being an American. So when Maria was denied a license because of Gov. Pete Ricketts' adherence to an unfair and unlawful edict, she joined with several of her fellow Dreamers to challenge it in court. But rather than simply waiting on a court to decide, Dreamers and their allies, including the Nebraska Chamber of Commerce, convinced the legislature to consider a bill to reverse the discriminatory policy.

At first, it seemed like a long shot. Republican members of Congress are trying to scrap DACA altogether. Republican governors and attorneys general in 26 states — including Nebraska — are suing to stop the DACA program from expanding. How were Dreamers going to convince a majority of Republicans to override their Republican governor?

Ask them. Last week, the legislature passed a bill ensuring that Dreamers with DACA — and anyone else with deferred action — are eligible for driver's licenses. When the governor vetoed the bill, the senators stood strong, and voted 34-10 to override the veto. This vote is a victory for Dreamers, and for all Nebraskans.

But it is also of national significance for two other reasons.

First, it successfully concludes nearly three years of a nationwide, state-by-state legal and political struggle by ACLU and partner organizations to support Dreamers' fight to win recognition of their right to driver's licenses. As soon as President Obama announced his DACA initiative in August 2012, most states embraced the opportunity to integrate young immigrants and to ensure that they are trained, tested, licensed, and insured as drivers. Some states, however, vowed to deny driver's licenses to them. Others stonewalled.

There was more than driving at stake. For states and Dreamers alike, a driver's license symbolizes belonging, membership, and acceptance. In most cases, recalcitrant state officials relented in the face of strong legal advocacy, organizing, and the broad public consensus favoring fair treatment of Dreamers.

Three states held out: Michigan, Arizona, and Nebraska. Dreamers had little choice but to sue, with the support of ACLU and other partners. Michigan began issuing licenses soon after being sued. Arizona began issuing licenses earlier this year, after the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit found that the state's policy violated the U.S. Constitution. This left Nebraska standing alone, the last state clinging to discrimination.

Wisely, rather than await yet another unfavorable court ruling, the legislature took the affirmative step of passing a law to end two governors' losing battle. The law is effective immediately, meaning that Dreamers granted DACA finally have the right to apply for driver's licenses in all 50 states.

Second, the Nebraska vote brings an underreported trend to the surface: the unwillingness of state legislatures in both red and blue states to penalize Dreamers and others granted deferred action.

Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach, the architect of numerous failed anti-immigrant state laws, boasted earlier this year that he was in consultation with lawmakers from a dozen other states about state legislation to target Dreamers and others who benefit from federal executive actions on immigration.

Yet from Kansas to Georgia to Texas, Republicans state legislators are refusing as a matter of state policy to penalize Dreamers. Why? It's one thing to file a bill attacking Dreamers, and it's quite another to have to face them, hearing after hearing, and to listen to their stories, which always disrupt simplistic stereotypes regarding "illegal immigration."

The media rebroadcasts those stories of young people overcoming extraordinary obstacles to contribute actively to their communities, and public opinion turns even further against legislators seeking to punish Dreamers. The Nebraska vote is another strong indication of support, on the ground, for Dreamers and the presidents' deferred action initiatives. Republicans may disagree with the way in which the president has gone about his reforms, but they appear to agree with the policies themselves.

Either way, Maria Marquez Hernandez, other Dreamers, and their allies will keep fighting — and winning.