United States v. Carpenter

Digital Privacy Goes to the Supreme Court

In 2011, FBI agents in Detroit obtained several months’ worth of location records from cellphone companies for suspects in a robbery investigation — all without a warrant. They were able to do so because of an outdated legal theory called the “third-party doctrine” that has been used by law enforcement to access personal data without ever having to demonstrate probable cause to a judge.

Timothy Carpenter, represented by the ACLU, argues that the government violated his Fourth Amendment rights when it obtained his location records without a warrant. The court’s decision in the case will also have implications for the extent of the Constitution’s protections against warrantless search and seizure of much of the private data collected and stored by current technologies.

The Right to Keep Personal Data Private: Carpenter v. U.S.

If the justices were to apply the government’s 1970s-era view of the third-party doctrine to cellphone location data, it could throw open a huge array of highly sensitive digital records to warrantless access by police.

A Privacy Case Before the Supreme Court Is About Press Freedom, Too

A discussion of Fourth Amendment privacy safeguards isn’t complete without considering how those safeguards — or lack thereof — might impact First Amendment rights. For journalists, any threat of government surveillance has a chilling effect on newsgathering activity and can make sources think twice about talking to reporters.

What the Founders Would Say About Cellphone Surveillance

The Fourth Amendment arose from the Founders’ concern that the newly constituted federal government would try to expand its powers. Based on experience under British rule, they knew that equipping government officers with unfettered discretion to search and seize would be a formidable means of oppressing “the people.”

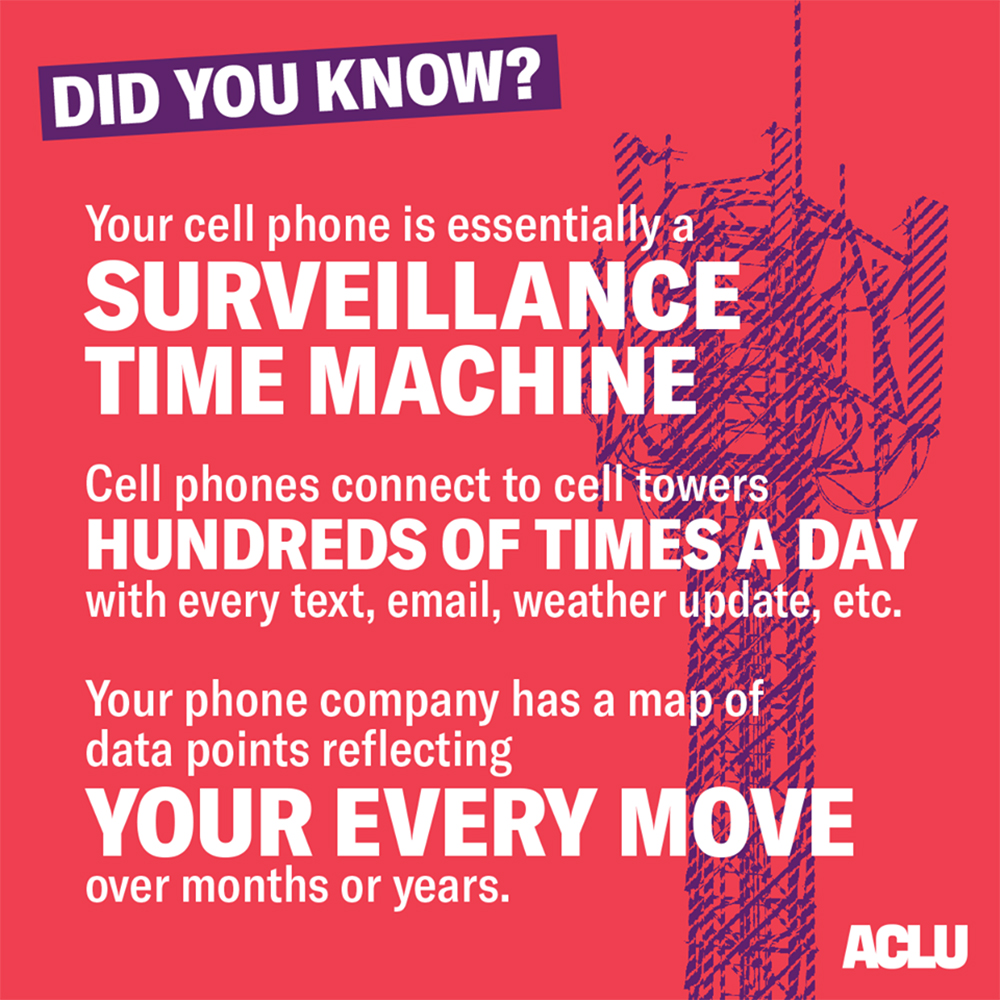

Infographic: A Surveillance Time Machine

In 2011, federal investigators obtained more than four months of Timothy Carpenter’s cell phone location data from his service provider without a search warrant during a criminal investigation in Detroit. The data revealed thousands of his location points. These location records can reveal an incredible amount of private information and should absolutely be entitled to Fourth Amendment protection. The Supreme Court’s decision will set a precedent for years to come, making it crucial that it ensures that the police are subject to limits on search and seizure in the digital age.

Other Links:

- How the Supreme Court could keep police from using your cellphone to spy on you (Washington Post op-ed)

- The Supreme Court’s privacy precedent is outdated (Washington Post op-ed)

- If cops can get phone data without a warrant, it could be a nightmare for journalists — and sources (Washington Post column)

- Cops, Cellphones and Privacy at the Supreme Court (New York Times editorial)

- Planet Money: Your Cell Phone's A Snitch

- A Federal Court Says Your Prescription Records Aren’t Really Private. The Supreme Court Might Have Something to Say About That.

Privacy & Technology

Free Speech

A Privacy Case Before the Supreme Court Is About Press Freedom, Too

Privacy & Technology

The Right to Keep Personal Data Private: Carpenter v. U.S.

Privacy & Technology