The Making of the Right to Abortion

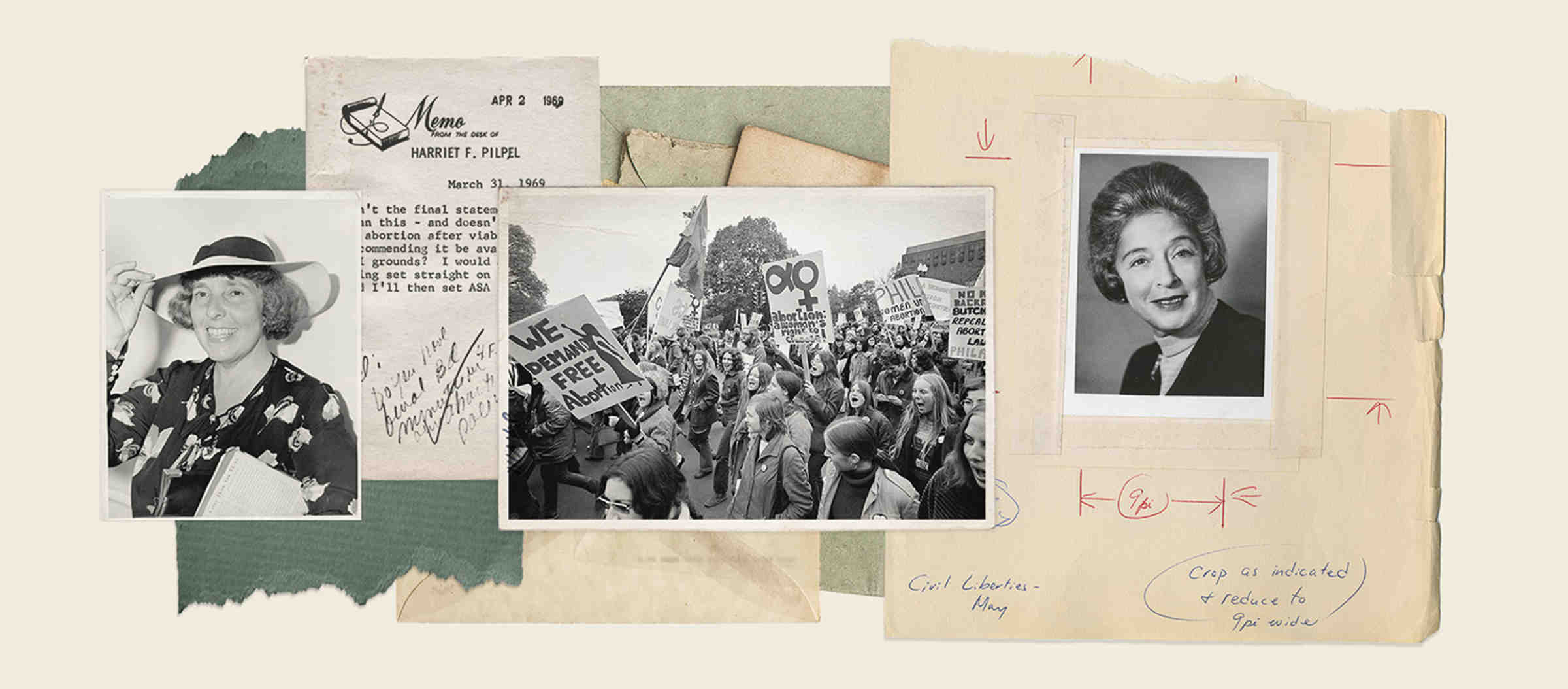

“I am far from being a feminist,” Dorothy Kenyon announced in 1968 to colleagues on the American Civil Liberties Union’s national board. But I “care passionately for fair play,” she assured them. Harriet Pilpel, another prominent board member, also distanced herself from feminism — so much so that, in 1973, self-identified feminists who had recently joined the board whispered that Pilpel did not “consider Feminist concerns her own or savor the bonds of sisterhood.”

To Kenyon and Pilpel, feminism smacked of man-hating. Worse, it threatened to undermine the camaraderie they had long relied on to persuade male board members to treat women’s rights as civil liberties. Even so, in the 1950s and 1960s, Kenyon and Pilpel introduced their colleagues on the ACLU board — mostly men — to the idea that laws against abortion might involve civil liberties, and they did so in surprising ways and within unlikely contexts.

Dorothy Kenyon, July 31, 1939

Barney Stein/New York Post Archives /(c) NYP Holdings, Inc. via Getty Images

‘Self-Determination in Childbearing’

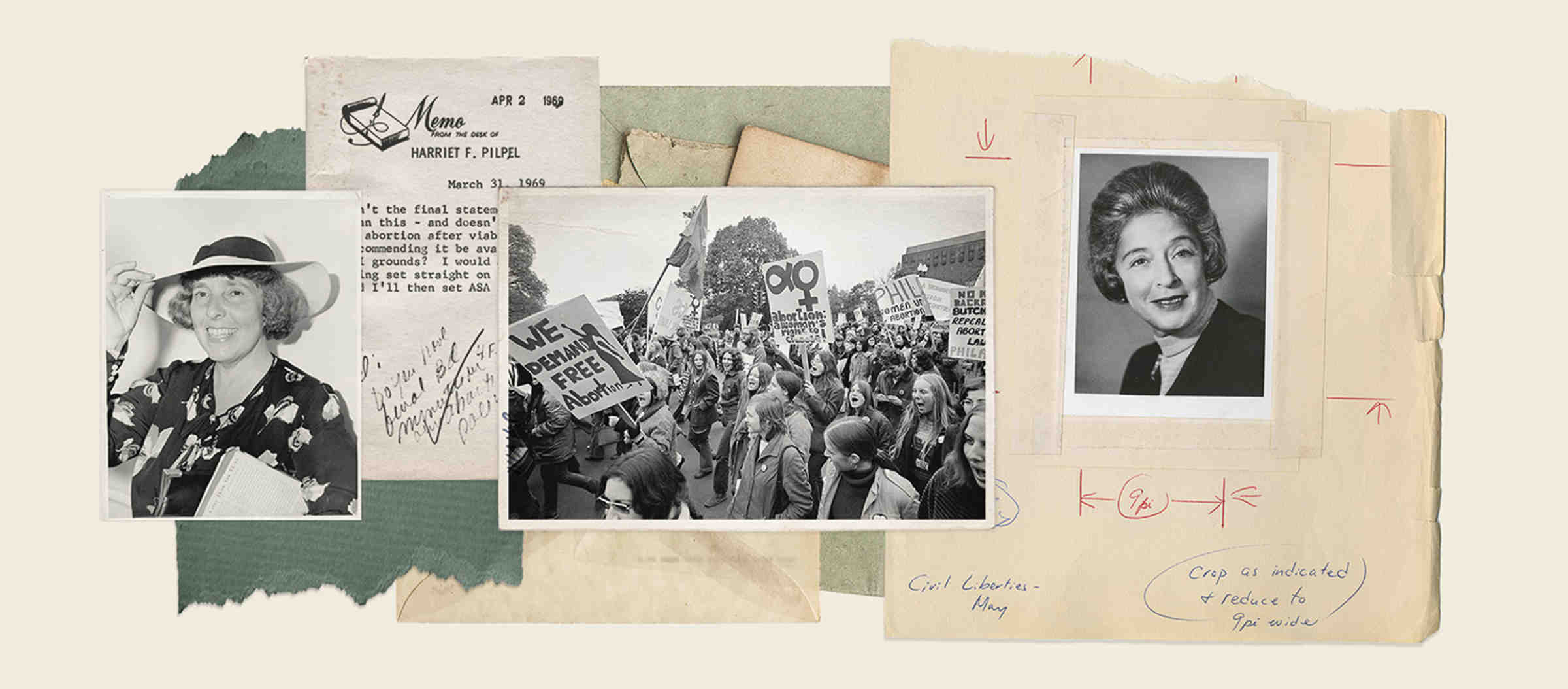

The men who led the early ACLU in the 1920s were familiar with abortion. As participants in the sexually experimental social scene that distinguished Greenwich Village, many appreciated that abortion, even though illegal, could provide a back-up when contraception failed. Roger Baldwin, a founder and longtime director of the ACLU, for example, knew that his aversion to fatherhood led his first wife to have at least one abortion.

Even so, in the beginning of the 1930s, after becoming one of the only female board members, Dorothy Kenyon tried repeatedly and without success to raise the issue of abortion. Harriet Pilpel was younger than Kenyon by more than two decades and did not join the board until the 1960s. But by 1936, she was already working with her law partner Morris Ernst to overturn laws against birth control, and by the 1940s, she advocated repeal of all laws that criminalized common sexual practices, including those against abortion.

Kenyon did not convince the board even to discuss abortion as a possible civil liberties matter until 1956, and only after a Virginia-based contributor, Jules E. Bernfeld, urged the ACLU to go after laws that prevented “self-determination in childbearing.” But that discussion resulted in no action; board members concluded that abortion fell outside their purview, because they could not determine when life begins. That, Kenyon argued, was not the point. Women must have the “right to choose what shall happen to their bodies,” she insisted. Nevertheless, the ACLU decided to leave the matter to “social agencies in the field.”

Kenyon gained a new ally a couple of years later when Melvin Wulf arrived as the ACLU’s assistant legal director. Wulf made no secret of his support for abortion rights or of his personal familiarity with the issue. After arguing in Poe v. Ullman (1960) — unsuccessfully, it turned out — that laws against birth control violated rights to privacy, he considered the possibility of attacking laws against abortion on the same grounds.

Read the Entire ACLU 100 History Series

Source: American Civil Liberties Union

Ironically, although leaders of the Planned Parenthood Federation of America (PPFA), represented by Harriet Pilpel in Poe, sided with Wulf, they were reluctant to envision birth control on a continuum with abortion. After all, they had worked for decades to distinguish birth control from abortion as a strategy for destigmatizing and legalizing it. They had, in fact, argued that birth control was abortion’s antithesis because it would prevent abortions, not make them more available.

Abortion Rights Begin to Go Mainstream

Even as the ACLU and PPFA coordinated a campaign to overturn laws against birth control, others were developing a full-blown movement focused on legalizing what they called therapeutic abortion. First among them was the American Law Institute (ALI), an organization of leading attorneys and judges who had worked, since 1951, to create a “Model Penal Code” that would guide state legislatures in reforming their criminal laws.

By the late 1950s, the ALI recommended legalization of therapeutic abortions, defined as abortions performed by physicians to end a pregnancy that threatened the mental or physical health of the woman or one with severe fetal anomolies. “[R]ape, incest, or other felonious” intercourse might also justify an abortion.

As if on cue, the 1960s brought a wide range of new demands for abortion — from women who helped to generate the decade’s sexual revolution to women who wanted to control the number and spacing of their children. Discoveries that thalidomide and rubella caused serious fetal anomalies emerged in the middle of a rubella epidemic and also brought new supporters to the movement to legalize therapeutic abortion.

By the middle of the 1960s, high-profile allies included the Christian Century magazine and the National Council of Churches, as well as a number of mainstream media outlets, law reviews, deans of law schools, and state medical societies and bar conventions. Meanwhile, abortion law reform groups formed all over the country and demanded “humane abortion laws,” beginning in California when the legislature considered bills that would decriminalize therapeutic abortion.

Despite Kenyon’s persistent advocacy, the ACLU came late to the issue. In 1963, even the director of its most progressive affiliate — the one in Southern California — insisted that “there is no prospect that the ACLU will regard ‘Therapeutic abortion’ as a civil liberties matter.”

Even so, just one year later, Harriet Pilpel, recently elected to the national board, brought the issue of abortion to the ACLU’s 1964 Biennial Conference in Boulder, Colorado. Created in the 1950s as a strategy for more fully involving lay members and the affiliates in shaping ACLU policy, the biennial had become the place for activist members to initiate change. Indeed, resolutions passed at biennial meetings became formal policy if the national board did not reject them within 18 months. If the board did object, the resolutions were submitted to a vote by the ACLU’s affiliate boards.

Pilpel went to Boulder determined to come away with a resolution on abortion.

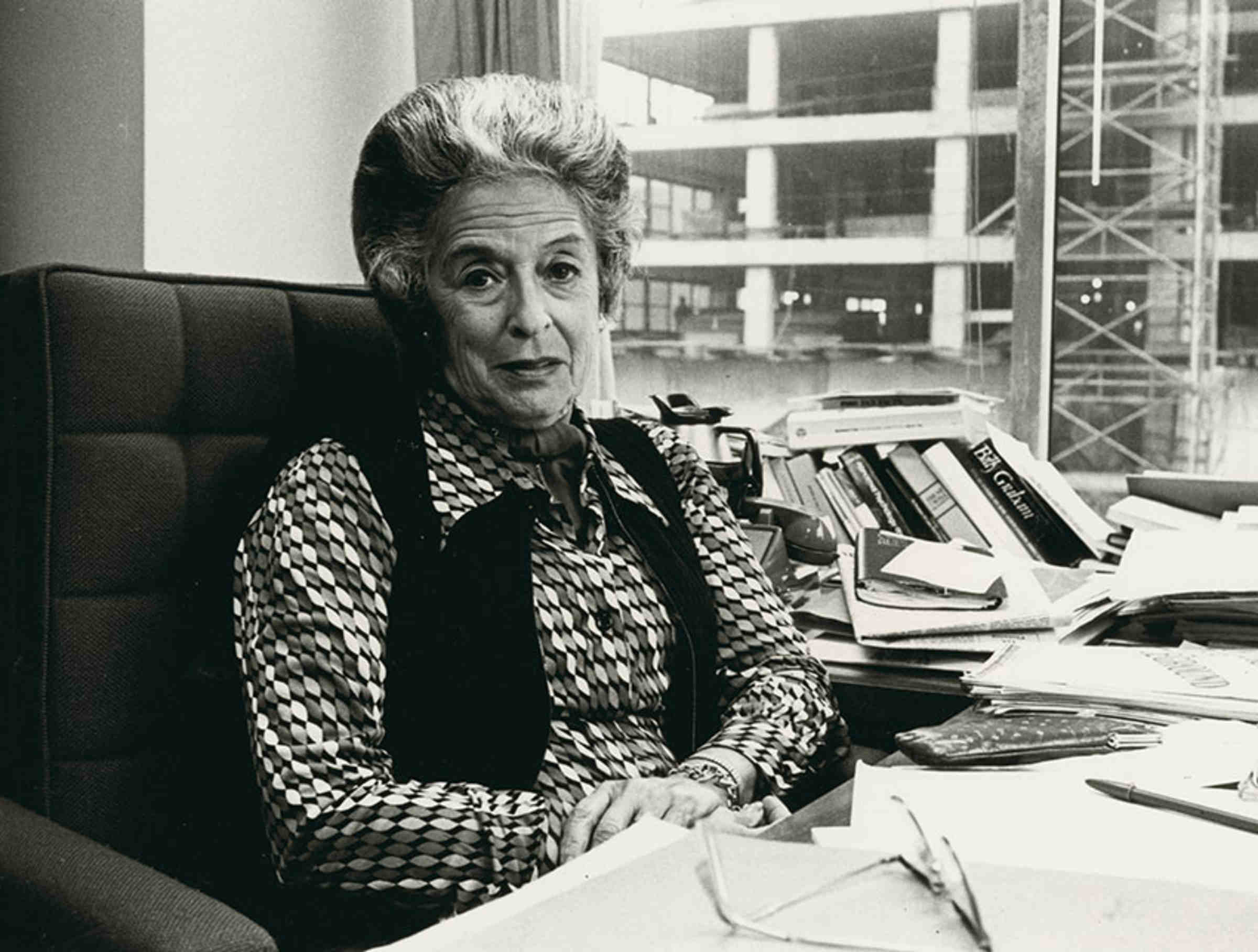

ACLU General Counsel Harriet Pilpel in her office, 1980

ACLU Archives

‘There’s Something Wrong With the Laws’

The 1964 biennial had a packed agenda. The meeting was dominated by the civil rights crisis in Mississippi as participants strategized about how the ACLU could help prevent violence from overtaking the summer voting rights project. President John Kennedy’s “war on crime,” another major issue, also occupied attendees, who worried that a war on crime could trigger new abuses of civil liberties.

Pilpel actually presented her appeal for abortion law reform on a panel titled, “Civil Liberties and the War on Crime.” Laws against abortion and other “sex laws” constitute a form of “class legislation,” she argued. They are enforced primarily against the poor and underprivileged who suffer “wholesale violations of civil liberties” through surveillance, entrapment, arbitrary police action, speech repression, and intrusions on their privacy.

Relying heavily on the work of sex researcher Alfred Kinsey, one of her clients, Pilpel claimed that, under these laws, nine out of 10 Americans qualify as sex criminals. “There’s something wrong with the laws,” Pilpel declared, when elites violate them with impunity, while the poor and people of color suffer prosecution and punishment.

“The American Law Institute has pointed the way,” she noted, to establishing a right of sexual privacy that would encompass rights to birth control and abortion. But it was up to the ACLU, she insisted, to tease out and defend the civil liberties issues involved.

Pilpel prevailed over the opposition of a vocal minority. The 1964 biennial voted to adopt ALI’s recommendation to decriminalize private sexual conduct by consenting adults and instructed the ACLU to explore the constitutionality of abortion laws. She was delighted.

In addition to moving sexual rights, in general, and abortion, in particular, onto the ACLU’s agenda at the biennial, Pilpel also forged a new and powerful relationship there. “One of the nice things” about the conference, she wrote to Dorothy Kenyon, “was the feeling of having become friends.”

Indeed, the two attended panels together, debated issues, enjoyed sightseeing in the mountains, and later exchanged letters celebrating their newfound friendship. Thereafter, they vacationed together on Martha’s Vineyard and joined forces to persuade the national board to recognize the right to abortion as a matter of civil liberties.

Responding to Pilpel’s triumphant biennial resolution, the national board researched possible constitutional bases for attacking laws against abortion. Griswold v. Connecticut (1965) — a major Supreme Court opinion that relied in part on briefs submitted by Pilpel, for PPFA, and Wulf, for the ACLU — soon eased the task. It overturned laws against birth control by finding in the U.S. Constitution a right to privacy, one that ACLU leaders quickly deployed against abortion laws.

Policy details came together more slowly and with a fair bit of acrimony. Even Pilpel and Kenyon disagreed about whether and how a woman’s right to an abortion should be restricted. Others argued that a married woman must obtain her husband’s consent or that the rights of a fetus trumped those of a pregnant woman. Some argued for the rights of the unborn and the state’s interest in preserving fetal life.

Kenyon denounced the “bodily slavery” that laws against abortion imposed on women.

Kenyon called the discussions “a shambles of irrelevance and illogic,” and she despaired at seeing civil libertarians steadfastly refusing to apply civil liberties principles to abortion. Like “a Cassandra crying out in the A.C.L.U. wilderness against the crime of our abortion laws and man’s inhumanity to women,” Kenyon denounced the “bodily slavery” that laws against abortion imposed on women. A democracy in which women are “forced by the government to bear children against their will” is a mockery, she insisted. “Only Hitler could create the obscenity of women’s bodies belonging (in this crucial function of theirs) to the state."

The ACLU, and the Supreme Court, Comes Around

After years of negotiations, the board in 1969 articulated the following policy:

The Union asks that state legislatures abolish all laws imposing criminal penalties for abortions. Total repeal of all such laws will meet these civil liberties criteria.

Kenyon expressed her delight in a letter to Jules Bernfeld, the Virginia donor who helped her persuade the ACLU to discuss abortion for the first time in 1956. “I’m happy as can be,” she wrote him, “that the end seems almost in sight. Isn’t it fun to be almost prophets?”

She also forwarded her original correspondence with Bernfeld to the ACLU’s associate director for preservation as “a footnote to history.” It was to Bernfeld, she added, that “I first made my remark about women’s right to control their own bodies,” an idea that initiated the campaign to repeal abortion laws. “I am free now,” she told another colleague, “to shout abroad that this policy of mine is also that of the A.C.L.U.”

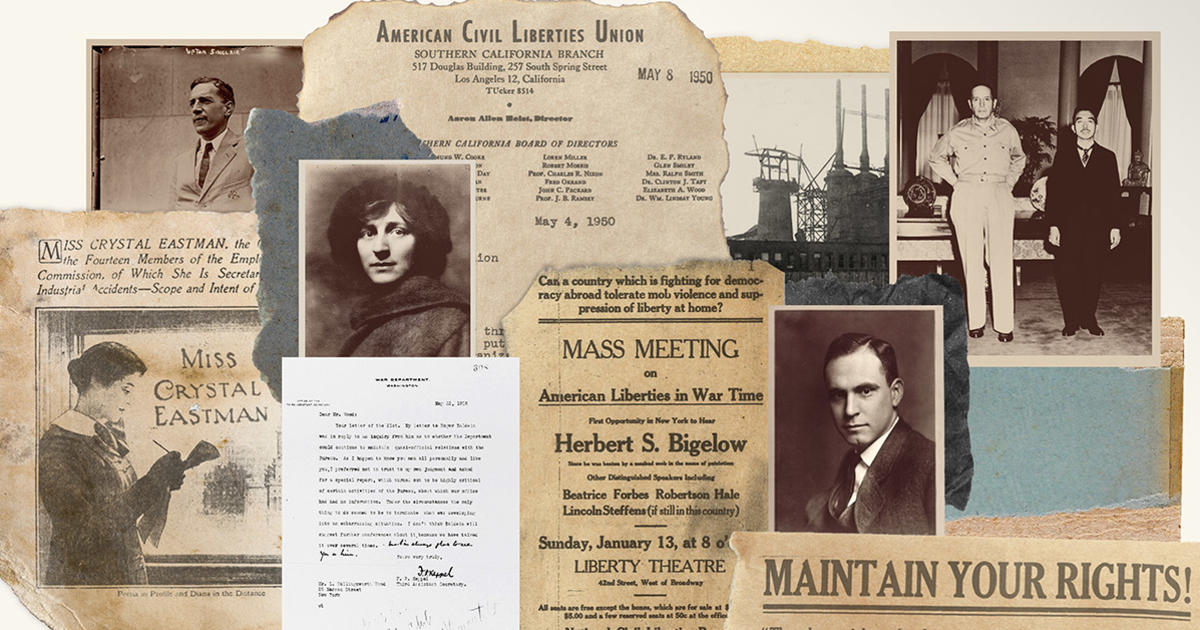

Demonstrators demanding a woman's right to choose march to the U.S. Capitol for a rally seeking repeal of all anti-abortion laws in Washington, D.C., Nov. 20, 1971.

AP Photo

The ACLU immediately joined a number of promising abortion cases, including Doe v. Bolton and Roe v. Wade. Pilpel stepped up to recruit and coordinate amicus briefs, hoping to present the strongest case for a woman’s right to abortion by mobilizing social science research and arguments from the medical and legal professions as well as agencies representing the poor, women’s rights, and other “public spirited organizations.” She also planned and executed moot court sessions with the local attorneys who would argue the cases to prepare them for the aggressive questioning they would encounter before the Supreme Court.

Pilpel celebrated on Jan. 23, 1973, when a 7-2 majority on the Supreme Court declared the “right of privacy…broad enough to encompass a woman’s decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy.” The court imposed limits on a pregnant woman’s rights, allowing the state to intrude on her privacy to “safeguard health,” “maintain medical standards,” and “protect potential life.”

To balance the woman’s rights with the state’s interests, the court created a trimester timetable according to which a woman’s rights would give way over the course of the pregnancy to the state’s interest in preserving her health and the life of the fetus. The court also struck down statutes that restricted abortions to particular types of hospitals, required external approval, or imposed residency requirements.

According to ACLU attorneys at the time, the court's opinion immediately invalidated abortion laws in 43 states, including 13 that had recently adopted ALI-type reform legislation. It also halted 30 other abortion cases with which the ACLU and its affiliates were involved and sent state legislatures back to the drawing board — some to challenge the Supreme Court’s holding, others to bring their laws into compliance. The virulent antiabortion movement that emerged inspired the ACLU to develop a long-term strategy for preserving what it came to call reproductive freedom.

Kenyon and Pilpel’s Legacy

Kenyon did not live to see Doe and Roe. Already, in 1969 — even as she exchanged congratulations with Harriet Pilpel and Jules Bernfeld over the ACLU’s new policy on abortion — Kenyon suffered symptoms related to the stomach cancer that would end her life at age 83 in 1972.

Pilpel felt the loss of her friend and co-conspirator keenly. Together, she and Kenyon had — with the crucial help of Wulf and others — moved the ACLU, the nation’s most important civil liberties organization, to recognize and fight for women’s right to abortion, something it continues to do today. They did so before the emergence of second-wave feminism, working within institutions — the ACLU, state legislatures, and the judicial system — that included very few women.

These few women had to persuade men to recognize that laws against abortion violated human rights to control one’s own body — rights that only women and no men sacrificed when sexual intercourse resulted in an unwanted or dangerous pregnancy. Kenyon, Pilpel, and countless others did this in the decades between 1930 and 1970 partly by disavowing feminism, but also by insisting — as First Lady Hillary Clinton would defiantly declare in 1995 in Beijing, China — that women’s rights are human rights. In doing so, they laid groundwork for feminists to take the ACLU and the world by storm.

Leigh Ann Wheeler is professor of history at Binghamton University and the author of "How Sex Became a Civil Liberty" (Oxford University Press, 2014) and "Against Obscenity: Reform and the Politics of Womanhood in America, 1873-1935" (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004). She is currently writing the biography of popular memoirist and civil rights activist Anne Moody.