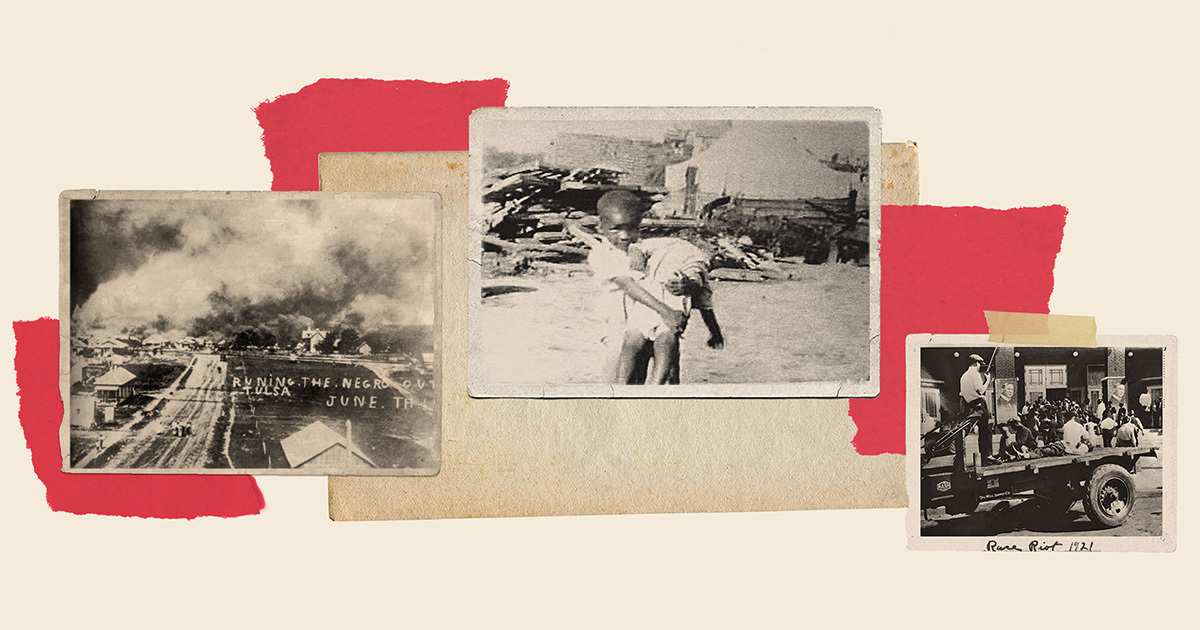

Chicago Paves the Way for Reparations for Police Sadism

For more than two decades, starting in the 1970s, former Chicago police commander, Jon Burge, led a group of officers in the Chicago Police Department, who tortured Black and Latinx men, women, and children in order to extract false confessions. The techniques they used included electrical shocks to genitals, cigarette burns, suffocation, mock executions, sexual assaults, and more. At least 65 known torture survivors are still incarcerated due to the confessions elicited from the torture these men inflicted. Some spent decades in prison, and some died behind bars.

The legacy of police terror on the city of Chicago remains ever present and will continue to produce scars for years to come. The full magnitude of the practice of torture is still being revealed, and there may never be a full reckoning for the lives destroyed. Despite this, Chicago took an historic step forward in acknowledging the horrors committed by the CPD.

On May 6, 2015, the city of Chicago passed the nation’s first reparations ordinance for survivors of police torture. To date, this remains the only such legislation in the country. The ordinance provides five radically transformative elements:

- Financial redress to torture survivors

- Free access to the city’s colleges for survivors and family members

- The creation of a public memorial

- Mandatory teaching of the police department’s ring of torture to eighth graders and high school sophomores in Chicago public schools

- The creation of a center on the Southside dedicated to addressing the psychological effects of torture.

This story exists as an example to the rest of the country of how reparations can be made reality right now for injustices that exist within and outside of our view. The Chicago reparations ordinance for survivors of racialized police torture is also an example of what reparations for survivors of the trans-Atlantic slave-trade in the United States could look like today. But to understand why reparations are necessary, it’s critical to read the survivors’ stories, some of whom are still fighting for their freedom.

Read the full reparations series

Source: American Civil Liberties Union

The Tortured

On Jan. 25, 2019, Kilroy Watkins was freed from Lawrence Correctional Center prison after nearly 28 years having survived torture by Detectives Kenneth Boudreau and John Halloran of the Chicago Police Department, who forced him into signing a false confession in 1992.

Kilroy explains:

“Prior to trial, I testified during my suppression hearing that my alleged statement to police was the product of physical and psychological coercion applied by my detectives (under the command of Jon Burge from the Chicago Police Department). After both detectives denied inflicting such abuse, the trial court denied my motion to suppress, 'Finding the detectives to be more credible witnesses'. Without any other physical evidence, the trial court found me accountable of first degree murder, based essentially on the alleged confession. Since my arrest/trial, newly discovered evidence came to light of widespread and systematic pattern of torture and abuse of suspects by CPD-police officers, including my interrogating officers, which corroborate my longstanding claims that my confession was the product of physical and emotional coercion.”

While incarcerated, Kilroy filed a Freedom of Information Act request to access the police misconduct complaints against his torturers, Boudreau and Halloran. As a Chicago Tribune investigation in 2001 revealed, Boudreau had, as of that time, helped secure confessions from more than a dozen defendants in murder cases in which the charges were later dropped or the defendant was acquitted. Nearly 20 years later, the full scope of Boudreau’s torture is still coming to light. The true impact of his reign is still unknown.

“In Chicago, in particular, false confessions (are) a huge problem,” said Karen Daniel, director of Northwestern University’s Center on Wrongful Convictions. “We are the false confession capital of the country.” Nearly 1 out of every 6 murder exonerations that has taken place nationwide over the past decade has occurred in Illinois. The National Registry of Exonerations reports that Illinois has a false confession rate more than three times higher than the national average of 12%. Of this amount, the majority of false confessions come from Chicago at a rate of 1 out of 4.

And there are many more stories like Kilroy’s.

Flint Taylor demonstrates a mock-up of a shock box he accuses Chicago Police of using during an interrogation (Associated Press)

In 1992, 15-year-old Sean Tyler witnessed a murder. The juveniles CPD charged with the murder were not the people Sean saw. Instead, they were five other young people, the youngest being 13-year-old Marcus Wiggins. Young Marcus was tortured by CPD Commander Burge and his cronies into confessing to a crime he didn’t commit, as detailed in his complaint filed a year later against the city of Chicago, Burge, and other police officials and detectives. During Marcus’s trial, Sean served as the sole witness. The detectives working the case harassed and taunted Sean so severely that Judge Earl Strayhorn issued a protective court order against the police, stating that no police on or about the case were to have any contact with Sean Tyler without first contacting Judge Earl Strayhorn.

Burge and his torture ring would get their revenge.

Two years later, Sean, now just 17 years old, was arrested and tortured by Detectives Boudreau, Halloran, James O’Brien, and William Moser, some of the same detectives involved in Marcus Wiggin’s murder case. These same detectives who Judge Strayhorn issued a protective order on, then attempted to pin another murder on Marcus Wiggins, now including Sean Taylor as an accomplice. Marcus was proven to have been out of town and therefore was able to avoid conviction on this case. Sean, however, was in town, and sadly those detectives were able to bring forth charges against him for which he was convicted.

Sean Tyler had no criminal record. He was sentenced to 58 years. On Feb. 15, 2019, Sean was finally released after serving 25 years, completing his sentence. Sean continues to fight for a new trial to overturn his conviction and clear his name.

Marcus Wiggins is now 40 years old and continues to fight for his release. Sean and Marcus and the many others who also remain incarcerated are owed reparations. These are only three stories out of who knows how many — some of whom undoubtedly did not live to tell their tales of horror at the hands of the CPD.

Jon Burge (Associated Press)

But there has been some justice.

On June 28, 2010, Burge was found guilty of perjury and obstruction of justice for lying about the torture ring that he led as part of the CPD from 1972 to 1991. Burge was sentenced to four-and-a-half years in prison. Burge and his henchmen could not be held criminally or civilly responsible for their crimes of torture because the statute of limitations had run out. Under Burge, 120 people, primarily Black, were tortured.

I first became aware of Burge when I was 14 years old. I was handed a flyer by a person who tried to impress upon me the importance of exposing this hidden horror. I thought surely, this was an exaggeration. Despite the CPD violence I had witnessed in my childhood — including the daily practices of CPD harassing, arresting, and kicking children as we made our way home from school — the minimization and normalization of systemic violence was already deeply drilled into me.

As the years went on, more and more reports of exonerations began to emerge. A fuller picture was beginning to be painted outlining the breadth of violence and injustice waged on the Black community by the CPD. The freeing of the “Death Row Ten” led to the current moratorium on the death penalty in Illinois. In the last few years, we have witnessed the highest amount of exonerations in the history of Chicago.

This is good, but it’s not enough.

Jon Burge is a notorious household name in Chicago. But the detectives who Burge trained to inflict torture — like Boudreau, Halloran, and O’Brien — are not. Right now, Homan Square, a black site where over 7,000 people have been disappeared by CPD, sits and functions on Chicago’s West Side. The Torture Inquiry Relief Commission founded in 2009 has a backlog of over 480 cases from the Burge torture ring, and it has only successfully recommended approximately 38 evidentiary hearings, which allow for convictions to be overturned. As the Chicago Tribune reported, investigations often take many years, and so far, at least two men have died while waiting for their cases to be heard.

So much more work remains to be done. But it is essential to note that the work that has been accomplished so far has been revolutionary, necessary, and incredibly vital, paving the way to deepen our excavation of the trauma and pain that resulted from continued systemic violence.

Chicago has started to pay its debt. But it has not finished, nor has the harm inflicted by the state ceased. The process has involved legislative movement forward followed by municipal stalling and steps backward, as revealed by the actions of the former mayor of Chicago, Rahm Emanuel, who rejected the proposal to finance the public memorial, a core tenet of the reparations ordinance.

Meanwhile, the city only guaranteed funding through the end of this year, 2019, for the Chicago Torture Justice Center — the therapeutic center for survivors — which was mandated through the reparations ordinance. Full funding must be secured for the public memorial and the center for survivors if the city is to be held accountable for the injustice, torture, and devastation of families, communities, and individuals. It is not only a question of morality. It is an issue of what is due.

The Tortured Deserve Reparations

When the state tortures, when the state murders, when the state harms, it is then responsible for addressing the trauma, the pain, the loss, and the misery that results. Apologies issued by politicians and government officials are ultimately meaningless without concrete material redress to account for the loss of years, loves, income, education, health — as well as familial, community, and individual care. In addition, the massive psycho-social consequences that result to the individual, family, and community cannot be ignored and must be included in any reparatory packages.

Torture serves to disrupt and destroy safety and agency. The function of torture is to bring the person so close to the threat of death that the only consciousness that remains is awareness of devastating pain. Within this new limited reality, the only ability to cease this persistent pain is to elicit a confession. Confession used as the only option of breath, the only option of survival, is the carrot used by the torturer to cease the progression of encroaching death.

Torture is not a new mechanism of state brutality. It has a long history in the United States and can be traced directly back to tools of subjugation vital to the maintenance of slavery and the application of genocide of the indigenous population.

Slavery and genocide by themselves are economic, political, and social forms of institutionalized torture. These systems of torture involve complicated executive, legislative, and judicial measures to maintain its functioning, much in the same way police torture and police impunity are maintained today. Within this framework, we can appreciate the link between the police torture inflicted on Black Chicagoans as existing within a continuum of state violence exhibited against Black people that began with the capture of Africans into the trans-Atlantic Slave trade.

Edward Baptiste, historian and author of “The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism,” writes:

“Okah Tubbee, a part-Choctaw, part-African teenager enslaved in Natchez, remembered his first time under ‘what they call in the South, the overseer's whip.’ Tubbee stood up for the first few blood-cutting strokes, but then he fell down and passed out. He woke up vomiting. They were still beating him. He slipped into darkness again.”

Baptiste goes on later to explain:

“(N)either their contemporaries then nor historians since have used ‘torture’ to describe the violence applied by enslavers. Some historians have called lashings ‘discipline,’ to ‘correct’ lazy subordinates’ reluctance to work. Even white abolitionist critics of slavery and their heirs among the ranks of historians were reluctant to say that it was torture to beat a bound victim with a weapon until the victim bled profusely, did what was wanted, or both. Perhaps one unspoken reason why many have been so reluctant to apply the term ‘torture’ to slavery is that even though they denied slavery’s economic dynamism, they knew that slavery on the cotton frontier made a lot of product. No one was willing, in other words, to admit that they lived in an economy whose bottom gear was torture.”

Reparations are part of the process of revealing and exposing pain, violence, and misery made invisible. Reparations are an act of making conscious that which is denied name, denied voice, denied existence. Reparations, this side of revolution and after, are part of making possible a world where such violence is lessened and eventually eradicated. Reparations are also the acknowledgment that the consequences of trauma are complex, compounded, and have ripple effects across generations and communities. Therefore, the responsibility of the state to state-sanctioned violence must be vast, complex, and generational in its application.

The inclusion of a center dedicated to the psychological consequences of police torture and violence is a core part of the Chicago reparations ordinance, and it provides a glimpse into what a possible reparations plan for descendants of the slave trade could look like in the United States. By offering counseling in the traditional one-on-one model — as well as non-traditional methods, which reflect the center’s community counseling model through a politicized lens — the Chicago Torture Justice Center situates collective healing as part of a political, individual, familial, and community process that is not separate from existing political paradigms. Instead, it acknowledges that co-existing struggle for justice is a necessary and vital component to eradicating harm and fostering integration from traumas, which then enable the creating of spaces for healing to occur.

Descendants of the trans-Atlantic slave trade hold trauma within our bodies and our communities, which are then forced into suppression through continued unequal conditions that produce racialized disparities and poverty. Addressing these structural, governmental, and policy realities must be part and partial to any discussion of reparations, for as long as mass incarceration and policing exists, continued racialized state oppression will continue to enact further trauma producing ever further need to create reparative solutions. A first significant act of reparations for descendants of slavery is to abolish prisons and policing, which exist as some of the most dramatic sites of racialized present-day violence today.

CPD torture survivors Ronald Kitchen, Stanley Howard, Marvin Reeves, and Mark Clements, authors of the book, “Tortured by Blue: The Chicago Police Torture Story,” write:

“Burge and other cops in Chicago have long known they could do whatever they wanted to black men and anyone in the black community; however change is coming now, and justice cannot continue to be denied and delayed. Except for the short prison term Burge served, all the other torturers, city and police officials, prosecutors and judges got away with either participating in, turning a blind eye to, or covering up the torture scandal. It is our collective hope that history will continue to expose and shine light on their involvement in helping to create one of the largest police corruption scandals in US history.”

Mark Clements (Associated Press)

Reparations was won in Chicago due to the persistent unrelenting work of survivors, their families, community members, and radical attorneys like Joey Mogul and Flint Taylor, who for decades remained vigilant in exposing the horrors occurring behind closed doors. Years of marching, writing, and refusing to remain silent are what finally led to the historic passing of this nation’s first and only reparations ordinance for survivors of racialized police torture. It will be continued efforts that amass even greater support to further and deepen reparations for the many others equally deserving. It will take the blood, sweat, and tears of thousands more to make real ending the systems that facilitate and maintain systems of state torture, death, and violence.

Reparations are a standard form of redress that already exists in many historical examples from survivors of the Holocaust, South African apartheid, the Pinochet dictatorship in Chile, Japanese concentration camps during World War II, indigenous populations, and many more. Let the example of Chicago lay the framework for more reparations ordinances across the country. Let these stories of survival and struggle encourage more survivors to come forward and even more supporters to stand in solidarity. Let this conversation of reparations push forward deeper concepts of understanding and reparative responsibility to state-sponsored violence and expand our conceptions of freedom-making.

Together, we will win.