One of the challenges facing domestic drone policy is the question of how not only our Fourth Amendment privacy rights will be protected, but also our First Amendment rights to photography, as my colleague Jay Stanley pointed out yesterday.

We’re already seeing this issue come up. The drone wars have landed at the New Jersey legislature and advocates for constitutional rights are finding ourselves fighting on multiple—fascinating—fronts.

We strongly supported a bill in New Jersey that, like a growing number of states, would defend the public’s Fourth Amendment protections by requiring law enforcement to obtain a warrant before using a surveillance drone, to discard surveillance unrelated to a specific criminal investigation, and to publicly report on the use of drones. It would also ban the weaponization of drones. Overwhelming, bipartisan majorities of the legislature voted for the bill last session, but Governor Chris Christie vetoed it without explanation. So we went back to work on it this year.

But just when we thought we knew the lay of the land, along came a curveball: new drone legislation introduced in May 2015 that took us by surprise.

This new legislation makes it a criminal offense to use a drone to take a photograph of “critical infrastructure.” And what is “critical infrastructure”? Any “asset” whose incapacity—even partial incapacity—would have an impact on the physical or economic security, or public health or safety, of the state. This specifically includes highways, waste treatment facilities, bridges, tunnels, and more.

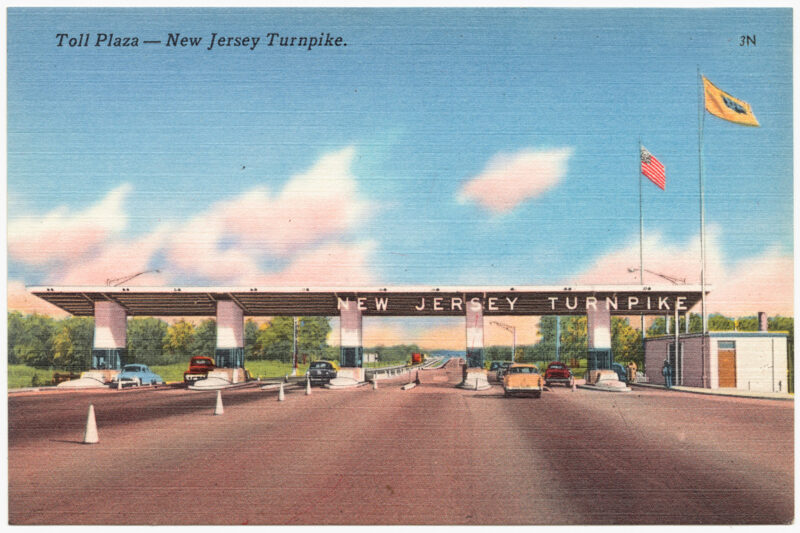

In New Jersey, this definition clearly includes the New Jersey Turnpike. So, to be clear, under this bill, if Simon & Garfunkel wanted to use a drone to count cars on the Turnpike as they looked for America, they’d be facing up to 18 months in jail.

The ACLU has long defended photographers’ First Amendment rights to film federal courthouses, transportation hubs, crime scenes, and even collaborated on a music video with Joseph Gordon-Levitt to make clear that there is a constitutional right to photography.

But at a hearing last month on New Jersey’s criminal drone photography bill, the Constitution was not on the agenda. Lining up in favor of the bill was the Chemistry Council—the trade group representing New Jersey’s chemical manufacturers—as well as the Chamber of Commerce and Business and Industry Association, two of New Jersey’s most powerful lobbying groups. Their testimony, however, spoke little to the threat posed by photography and instead focused on the danger of a drone crashing into critical infrastructure to destroy the power grid or to release a hazardous substance.

The First Amendment team included the ACLU, the New Jersey Press Association representing journalists, and the Academy of Model Aeronautics, a non-profit that promotes model aviation. Also, to our surprise, we learned that representatives of Google had arrived in Trenton to weigh in with their concerns about the legislation.

The business groups’ concerns about the use of drones as weapons are legitimate and policymakers might consider establishing limited no-fly zones to protect infrastructure vulnerable to attack from the air. Lawmakers should also be making sure that our “peeping tom” and trade secrets laws are enforceable in the context of drones.

But there has been no compelling reason offered to criminalize drone photography.

The general rule guiding the right to photography in public is that if you can lawfully be somewhere, you can lawfully photograph from there. Unless we are prepared to ban drones from our airspace altogether, it should not be a crime to photograph infrastructure visible in public.

The potential for drone photography as a tool for art, journalism, and activism is significant. Imagine the investigative public service journalism that could be done by a reporter using a drone to capture images of river pollution by an unscrupulous pharmaceutical manufacturer or of neglected and crumbling roads and bridges. This technology is too young to foreclose the possibilities of drones as an accountability tool.

It is also clear that if banning photography of critical infrastructure is the goal, the bill simply won’t work. Here in New Jersey, for example, we know that disabling the George Washington Bridge can definitely have an impact on the economic security of the State. But if this bill became law, you could still take pictures from a car crossing the bridge, or use a telephoto lens from the Hudson River, from the shore, from a helicopter or airplane—or just use public satellite imagery.

For civil libertarians, there remain many difficult questions about when and how to regulate drones. But in an age where cameras are now everywhere, we have an interest in ensuring that the government does not secure itself a monopoly. The right to photograph is one worth defending, whether on a cell phone or a drone.

The fate of New Jersey’s criminal drone photography bill remains unclear. We hear there will be roundtables for stakeholders to air concerns and hopefully reach a compromise. But the drone wars in state legislatures and in Congress are likely to continue unabated for years to come. If New Jersey’s experience is any indication, all guardians of the First Amendment should start paying attention.